A special project team worked on reviving a Toyopet Racer, Toyota's first racing car from over 70 years ago. This fifth installment highlights the efforts of the ladder frame restoration team.

This series features Toyota’s project to revive a legendary racing car—now on display at the Fuji Motorsports Museum—with a look at the project members’ efforts as well as the history and meaning behind the vehicle.

In this fifth article, Toyota Times showcases the struggles of the team tasked with producing the car’s body and the ladder frame. This first part focuses on the ladder frame, from design to fabrication and finishing.

Ladder frame, the vital foundation for the machine

The Toyopet Racer is a racing car dating back more than 70 years. Toyota produced only two units, which do not exist now. The restoration team had to make many key components from scratch based on old photos and drawings.

The largest of these components was the ladder frame, which consists of two longitudinal members that run along each side of the car, connected by several cross members in a ladder-like configuration.

The engine, transmission, and the body are mounted on this frame. It is the car’s true foundation and permits no compromise on strength or precision, and it must also be completed before other components.

Masashi Watanabe and Kunihiro Tsunekawa took on the challenge of designing and building this ladder frame.

Watanabe is in his seventh year at the company. He is normally involved in body design at the Body Technology Development Division, and entrusted with the same area for the restoration project.

Watanabe

My supervisor told me, “I recommended you for this project since you did Formula Student and I thought you would like it.” That’s how I got involved. I really like cars and building things, and I also worked on body design for Formula Student, so the prospect of making such an interesting car got me really excited. It is fascinating to create products by ourselves. I didn’t even know about the Toyopet Racer until I joined this project.

The ladder frame had to be finished first, while still encompassing many other related components. For this project, team members were assigned to specific parts, and two of us were assigned to the ladder frame. I was not sure if we had enough resources.

Tsunekawa, meanwhile, has been with the company for 18 years, the first 11 of which were spent at the Press Engineering Division. He started the restoration project at the Technical Development & Prototype Division, but has since moved on to work on BEV battery manufacturing at a different division.

Tsunekawa

I learned about this project from my supervisor, who recommended me as a project member with press and sheet-metal background. Until then, I had worked within the limited scope of press fabrication, so I figured this would be a good opportunity to see the whole car-making process. I knew about the first-generation Crown’s entry in the rally challenge in Australia, the cornerstone of Toyota’s motorsports activities, but I had never heard of the Toyopet Racer.

How to make a ladder frame

Now, ladder frames are used in trucks, buses, and certain SUVs designed for rugged conditions, thanks to their sturdiness. Back in the day, they were also found in ordinary passenger cars.

Both the Toyopet Model SD and its progenitor the Model SB truck used ladder frames. Although the blueprints remained in Toyota’s archives, it was a tough process converting the original hand-drawn diagrams into 3D data.

The team’s biggest challenge was figuring out how to build the ladder frame. Tsunekawa played a central role in that effort.

Ladder frames are typically cast from molds. Unfortunately, making such molds to build a single Toyopet Racer would go against the project’s policy of restoring it quickly at a low cost.

Instead, Tsunekawa worked with Watanabe to explore various manufacturing methods that would not require casting. Developing solutions for varied small-volume production is also a challenge for Toyota.

Since they needed to complete a ladder frame first, Tsunekawa and Watanabe were already hard at work figuring out the fabrication particulars while other project members were still in the deliberation phase.

Tsunekawa learned that the frame of Toyota’s C+pod, an ultra-compact two-seater BEV, is made using a specialized bending technique by partner company Taiho Seiki. The manufacturer handles everything from prototyping to production of the chassis and suspension components for Toyota vehicles. Tsunekawa hoped his team could take advantage of these techniques and contacted Taiho Seiki about the possibility of creating a ladder frame without molds for the Toyopet Racer.

Too big to make

At Taiho Seiki, Tsunekawa met with Tomomasa Takahashi from engineering, and Takahiro Shichi from parts manufacturing.

Hirakawa

They needed the material to be long and thick, which requires a considerable load in the forming process. And when I heard they wanted it mold-less, I wasn’t sure how far we’d get, but I spoke with Takahashi and Shichi to see if we could give it a shot.

Takahashi

As an engineer myself, the more difficult something seems, the more I want to take on the challenge. We have equipment that can continuously bend round metal pipes to form 3D shapes, so I thought we could try this approach.

Taiho Seiki had long been experimenting with bending techniques, but never at such a size. The team considered modifying existing equipment but realized this would also be too costly. After much deliberation, they decided to set up a simpler specialized apparatus.

Groundbreaking metal forming technology without presses or molds

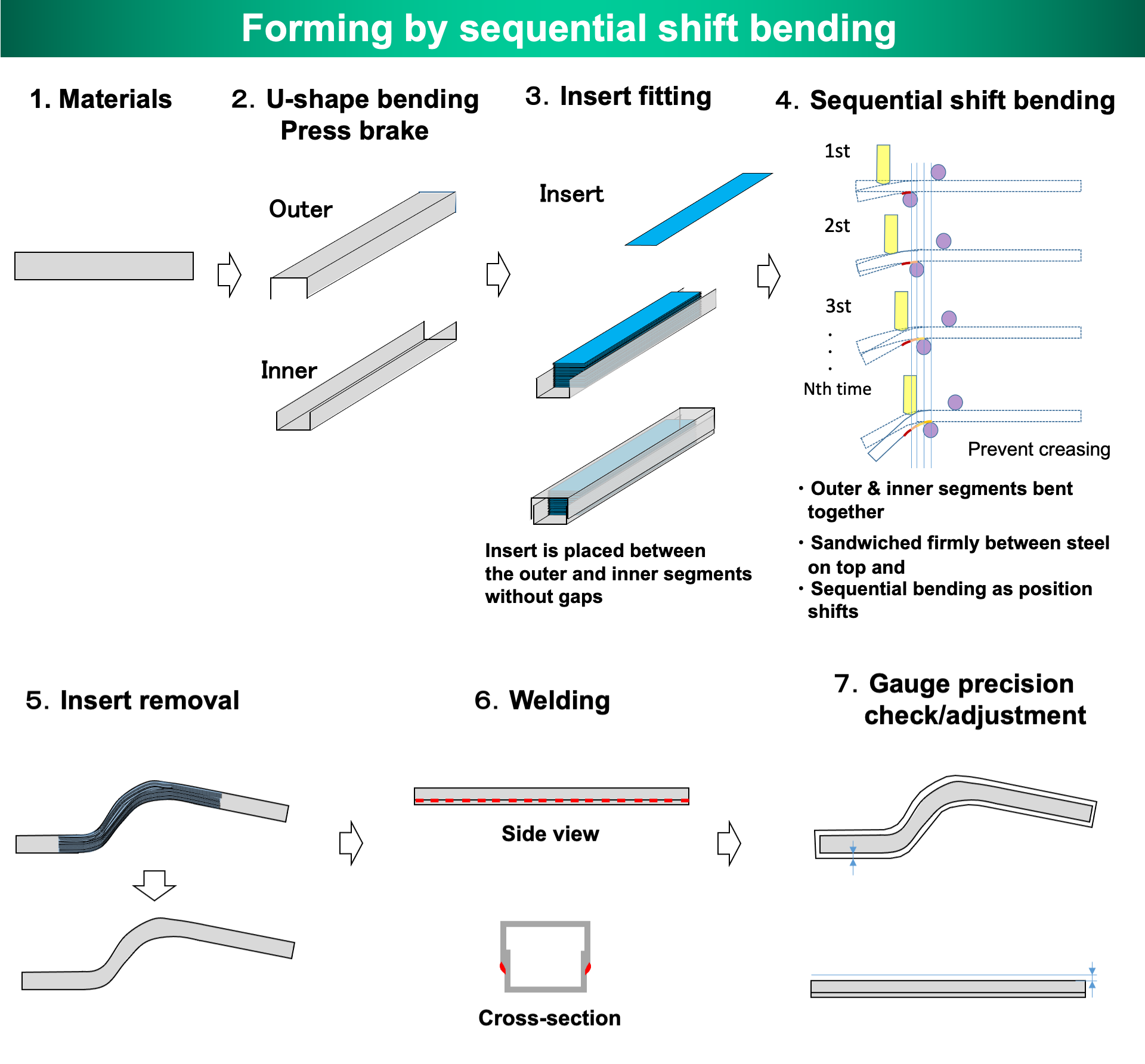

The team finally settled on a method for making the ladder frame with no molds. Their approach would come to be called “sequential shift bending,” for which Toyota and Taiho filed a joint patent application.

This processing method uses a newly developed bending machine to gradually form pipe-shaped metals by applying a moderate force and repeatedly shifting the processing point as the shape is formed.

Metal bending is inevitably accompanied by creasing and warping. However, this new process minimizes such deformation by filling the gap between the inner and outer metal layers with an insert that is firmly sandwiched in place from the top and bottom.

Once the metal has been machined into the desired form, engineers remove the insert and weld the sides of the outer and inner layers together, and measure the finishing precision.

Takahashi

We borrowed the idea from the bending process for small square pipes. With conventional methods, it would have been absolutely impossible to produce the frame within the given budget. This constraint pushed us to devise a new method.

Shichi

In more than 20 years of doing this job, this was my first time not using a press. Ladder frame production would use a large press of 1,000t or more. The molds would also have to be large. This groundbreaking method can achieve the same forms with a force of around 10t with no need for dedicated molds.

Tsunekawa

Ultimately, we were able to create a high-precision frame at about half the cost of conventional molding methods. I’m sure this technique will prove useful in many applications, both in-house and beyond the company.

This “sequential shift bending” method should be a great boon in restoring other classic cars for which molds are no longer available. Naturally, it can also be used in various other small-lot production.

Seventy years from its heyday, the Toyopet Racer spurred the current generation of engineers and technicians toward a new technological breakthrough.

The second part of this article will report on the fabrication of the upper frame and outer panels, which sit atop the ladder frame to form the racer’s cigar-shaped body.

(Text: Yasuhito Shibuya)