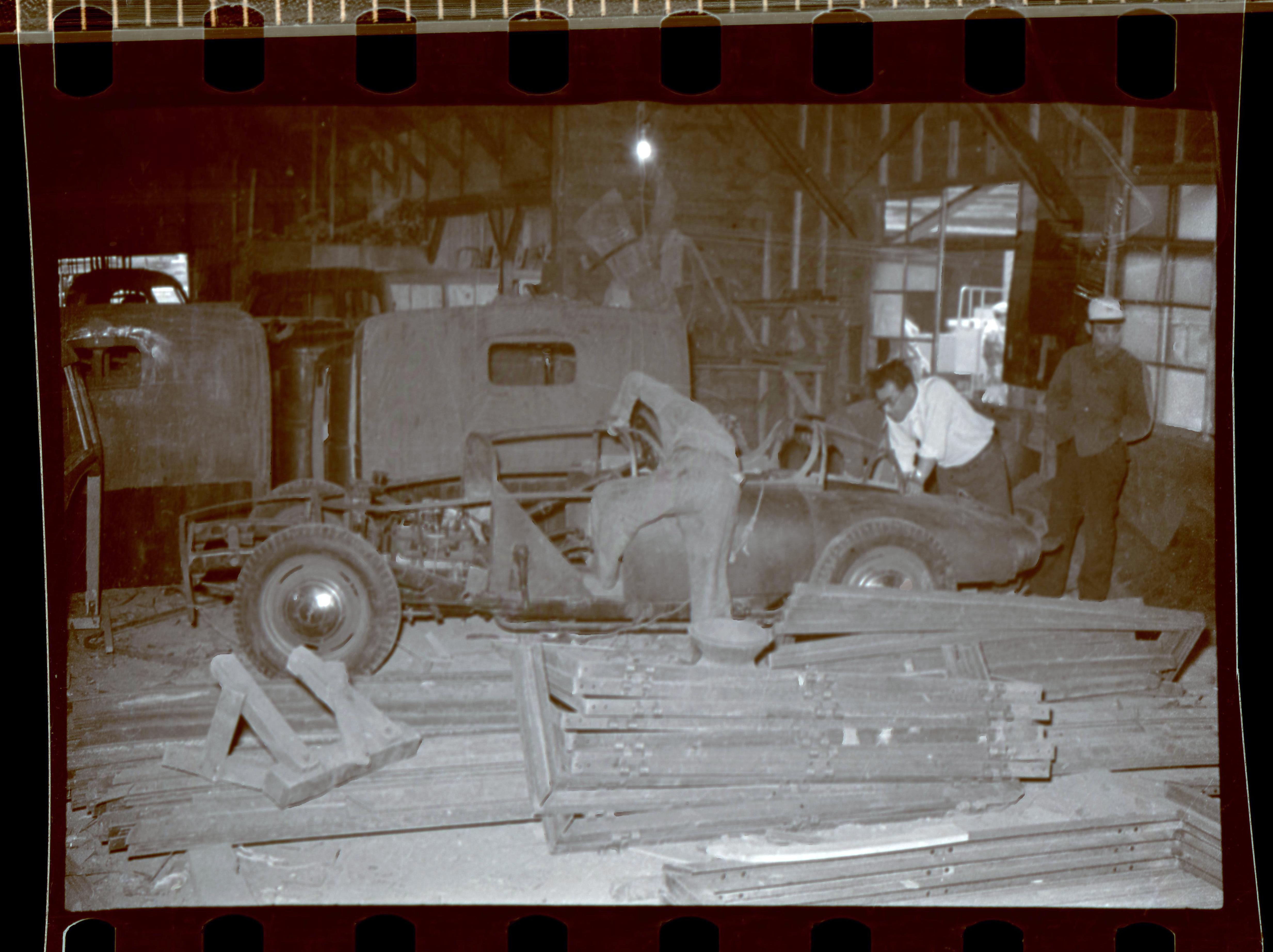

A special project team worked on reviving a Toyopet Racer, Toyota's first racing car from over 70 years ago. This fifth installment highlights the efforts of the ladder frame restoration team.

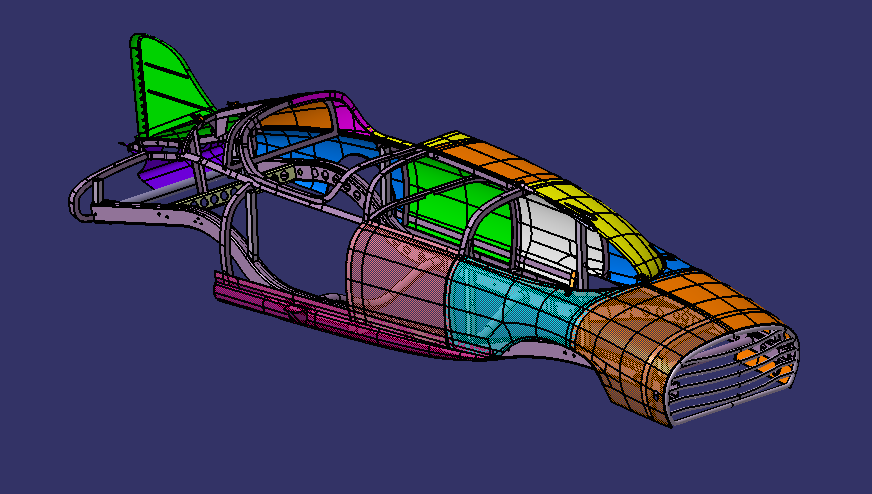

This second part of our body-focused special reports on the fabrication of the upper frame and exterior panels, which sit atop the ladder frame to form the racer’s cigar-shaped body.

Welding & hand-beaten panels: onto body fabrication

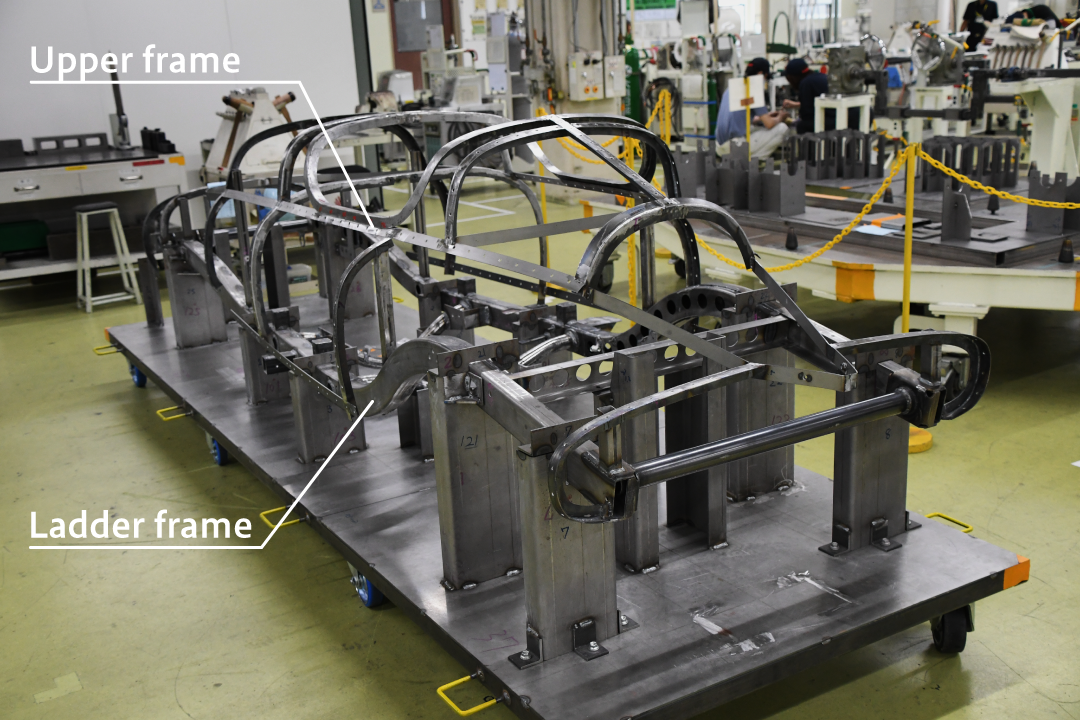

The next item on the agenda for the ladder frame restoration team was building the cigar-shaped body that encases the frame. The general process of constructing the body begins with the upper frame, which serves as its skeleton. Once completed, this upper frame is welded onto the ladder frame, then covered with body panels fabricated from sheet metal.

Tsunekawa

No drawings were available for the upper frame, only photos. We guessed that the frame would sit under the joints where body panels are riveted together, so I created 3D data for the upper frame based on old photographs and 3D design data reproduced by our designer. This was quite tough work.

Starting with upper-frame welding

Once Tsunekawa completed the 3D design, the team began building and welding the upper frame and fabricating the body panels in which it would be clad.

The sheet metal and welding skills needed for such work cannot be mastered overnight. Here, Tsunekawa drew on the expertise of two veterans overseeing the restoration project: the Technical Development & Prototype Division’s Eisuke Yoshino, a sheet-metal and welding specialist, and Kenji Komaru of the Powertrain Manufacturing Fundamental Engineering Division.

Satoshi Yasui, from the Technical Development & Prototype Division, was in charge of welding the upper frame crafted by these skilled hands to the ladder frame.

With the advice of the welding pros in his division, Yasui soaked up these new skills as he deftly welded on the upper frame. Another colleague, Haruyoshi Teramoto, supported Yasui’s work by measuring the finished ladder frame, as well as the shape of the upper frame welded to it, and providing the relevant data.

The great challenge of hand-beating sheet metal

Meanwhile, the team also began fabricating the racer’s body panels. This task was handled by Hitoshi Tsuchiya, who works under Yoshino, and a crew of young technicians. In all, 15 of Toyota’s junior employees, 10 of whom were involved in building the Toyopet Racer body panels, took part in the production process.

Tsuchiya

Honestly, we were full up with other work. Yet this is a key project for the company, and I’m proud that they were relying on our division. Since it’s also a good experience for our young technicians, I decided to take it on.

At this point, Tsuchiya and his crew had two challenging assignments. The first was to produce the panels, larger than any they had experienced before, by “hand-beating” sheet metal, just as it was done in the days of the original Toyopet Racer.

A time-honored craft, this technique involves manually pounding sheet metal into the desired shape with a hammer instead of using a press or similar equipment. Over his career, Yoshino has had experience fabricating large parts entirely by hand when building prototypes or concept cars. However, these days such jobs have all but disappeared.

Neither the young technicians who handled most of the sheet metal work—including Tetsuya Kondo, Kenji Naito, Yoshiki Horikawa, and Yasuo Yamada—nor their instructor Tsuchiya had experience with hand-beating parts as large as the Toyopet Racer’s body panels. Yoshino hoped to pass on the skills to a new generation by entrusting this work to the team’s younger members.

The second challenge was to complete the body panels without putty, using only welding and polishing to create a beautifully smooth finish.

Tsuchiya

We make the body panels by beating the thin sheet metal to fit our jig and then welding them together. The challenge here is that small dents form at the seams where the panels join. The most efficient way to eliminate these dents is to fill them in with putty, which Yoshino instructed us not to use.

In fact, the Toyopet Racer restoration team was strongly committed to this “no putty” rule. One of the project’s main goals was to impart Toyota pioneers’ skills, techniques, and spirit. Therefore, the team adopted an overarching principle: build parts using the original methods wherever possible. For the body panels, the butt welding was originally done by hand and not mended with putty. Although using putty in the restoration could certainly give a nice surface finish, the distinctive texture of hand-beaten sheet metal would be lost in the process. Above all, the decision stemmed from the team’s dedication to conveying the effort and passion of those who had come before.

However, not using putty means that body panels must be made to the required shape through hand-beating alone; the welding that joins panels must also be neat and dent-free to ensure a smooth finish. All of this raises the bar for those doing the work.

A seasoned veteran’s final lessons before retirement

After Yoshino set these two challenges for his young charges, they received passionate guidance from another Toyota veteran, Yasuo Yamashita. For Yamashita, seeing the body fabrication work through to completion was the final mission before retirement. His skill in hand-crafting large exterior panels is a treasured talent within the company.

Tsuchiya

Yamashita has the spirit of a true master craftsman, never compromising. He draws on his experience and intuition to add elements that aren’t depicted in 3D drawings. He insisted on perfection at every step, which was an invaluable experience, not just for the younger members but for myself as well.

Yamada

Until now, the largest parts I had made by hand-beating sheet metal were at most 30-40 cm long. It was my first time working on something so big, and I’m sure the guidance from Yamashita will greatly benefit me in my future work.

All told, Tsuchiya, along with Yamada and other young members, spent several thousand hours working on the sheet metal by hand. While doing this alongside their regular duties, they learned from Yamashita the vanishing skill of hand-forming sheet metal into large parts from Yamashita, and they also managed to complete the racer’s body panels.

The next step was to weld the body panels together and create a smooth finish without relying on putty. This was another difficult task for the younger members, however, they managed to get it done.

The confidence boost of taking on new challenges

The last remaining task was to assemble the body by mounting the panels on the upper frame and fastening them with rivet-style bolts, just as in the original Toyopet Racer photos. Of course, this process was no easy task. When the parts were put together, some areas inevitably don’t quite match up.

As a result, certain body parts had to be remade two or three times, and others required remachining during the assembly process. Tsuchiya and the young crew involved in this work agree that making these changes on the spur of the moment, provided more valuable experiences.

Horikawa

As the work progressed and we picked up the skills, the younger members began having fun and exchanging ideas about how to make improvement. I hope to pass these newfound skills on to next generations.

These sentiments were shared by Watanabe and Tsunekawa, who tackled the welding and sheet metal challenges alongside their younger colleagues.

Watanabe

That firsthand experience was invaluable, and I would never have tried welding if I hadn’t been part of this project. In figuring out how to move it forward, I also realized the importance of a constructive approach and the skills of bringing people together, like how to put everyone in a positive mindset. I want to apply these lessons to my future work.

Tsunekawa

The chance to interact with people from different fields greatly broadened my work perspective. Those personal connections I have built through the project will greatly help my regular prototyping. Being involved with the Toyopet Racer also made me more interested in cars than ever before. This has been a great gain for me.

The upcoming sixth installment in this series will feature the team that produced the car’s front axle I-beam by forging, another of the Toyopet Racer restoration project’s traditional manufacturing methods.

(Text: Yasuhito Shibuya)