This is an ongoing series looking at the master artisans supporting the automotive industry. In the 18th installment, we hear from a master engraver who crafts intricate emblem designs with metal carving techniques passed down from Japan's old Edo period (1603-1868).

Handwork still plays an important role in today’s car manufacturing, even as technology like AI and 3D printing offer more advanced methods. This series features the craftsmanship of Japanese monozukuri (making things) through interviews with Toyota’s carmaking masters.

This is the fifth and final part in our special series to mark the recent launch of the new Century by showcasing the craftspeople who work on the model.

The phoenix emblem is an iconic feature of the Century. We spoke with Koto Engraving Co., Ltd.’s Masashi Miyazawa, a master of engraving and polishing who prepares the all-important emblem molds, using traditional hand-carving and hand-polishing techniques that date back to the Edo period.

#18 Masashi Miyazawa, a master of engraving and polishing who creates intricate molds with techniques passed down from Edo craftspeople

Vice General Manager, Mold Division, Koto Engraving Co., Ltd.

The phoenix emblem, a symbol of Centuryness

While evolving to meet today’s needs, the new Century has also inherited the “Centuryness” built up over the model’s successive generations since its debut in 1967.

So what exactly is this Centuryness? Let’s return to the words shared by Yoshikazu Tanaka, who oversaw the car’s development, in an earlier Toyota Times interview.

“A traditional Japanese aesthetic and the ultimate in hospitality, made possible by uniquely meticulous attention to detail, combined with the exceptional craftsmanship of skilled takumi artisans. The new model has inherited this cherished carmaking philosophy, passed down through the generations from the original Century. This is what we mean by Centuryness.”

When it comes to the “traditional Japanese aesthetic” and “exceptional craftsmanship” that Tanaka talks about, one aspect that embodies Centuryness is the phoenix emblem.

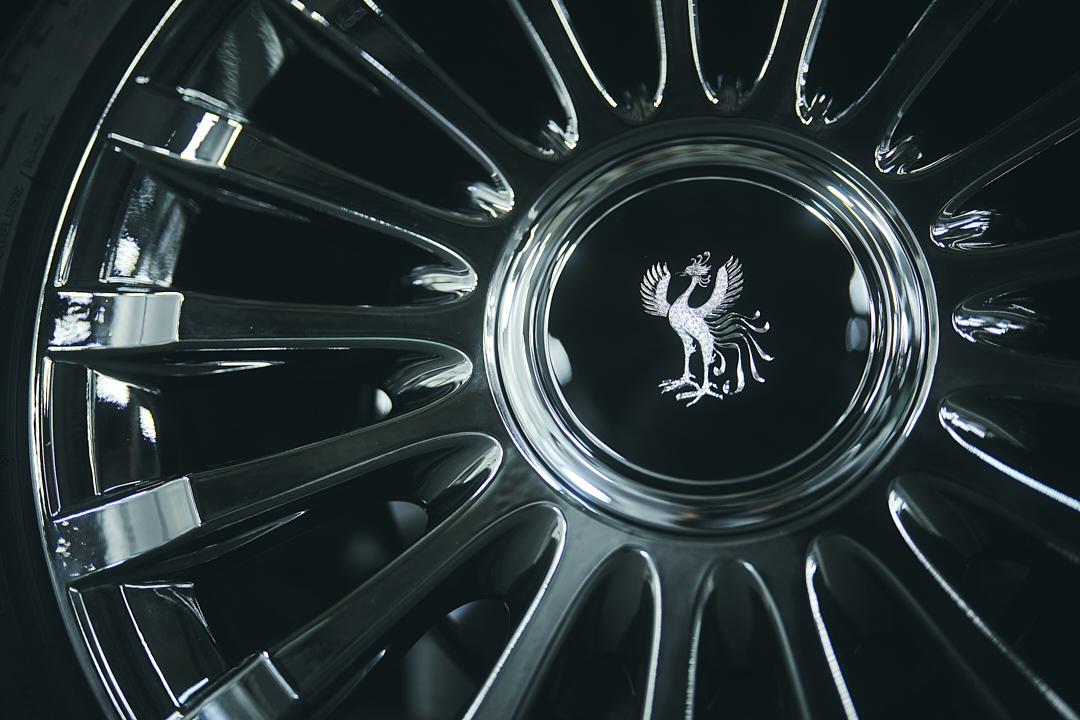

In the new Century, the phoenix—a mythological bird regarded as an auspicious omen—adorns the front grille, tailgate, and wheel centers. These emblems convey the Century’s history and grandeur into the present day.

The phoenix emblems also bring to life Edo chokin (metal engraving), a technique developed by the capital’s craftspeople during the Edo period and passed down to today.

Edo chokin is a traditional engraving style involving tapping keenly sharpened chisels with a hammer to carve intricate designs on metal surfaces. In the Edo period, it was used to decorate metal objects such as sword guards, furniture handles, and ornamental hairpins.

This engraving technique is used in producing the metal molds that shape resin into the Century’s phoenix emblem. These molds are made by Koto Engraving Co., Ltd., which designs and produces various parts and molds, not least for car emblems. The company’s business is centered on engraving techniques descended from Edo chokin, and Masashi Miyazawa is one of its craftspeople.

Following a father’s footsteps down the monozukuri path

The 51-year-old Miyazawa was born in Tokyo in 1972. He has worked exclusively in engraving and polishing since joining Koto straight out of high school, honing his skills as a true artisan. Today, he is a veteran craftsperson with 33 years of experience.

Yet, as it turns out, Miyazawa did not attend a technical school and after graduation, hoped to work at a conventional company. His father proved a key factor in moving to a monozukuri career.

Miyazawa

During the job-hunting period in my final year of high school, my father suggested, “Why don’t you come to work for us?” And so I just ended up joining the company. I hadn’t considered going into manufacturing, but upon coming here, I just really enjoyed the work, which spurred me to improve my skills so I could create more beautiful things.

In fact, Miyazawa’s father is Hideo Miyazawa, regarded as one of Koto’s two great engraving masters. Though Miyazawa recalls that he “just ended up” in the world of monozukuri, he had clearly taken the leap following in his father’s footsteps. Once at Koto, surely he underwent rigorous instruction from the masters…

Miyazawa

Unlike today, back then, the prevailing mood was that one should acquire skills on their own, and craftspeople like my father gave little guidance to younger workers.

However, whenever I wrapped up early, I liked to go around and talk to each of the older guys who were still around and observe how they worked.

Imitating the way they did things, trying out different techniques... I think repeating that process is what helped me grow.

Miyazawa says that becoming a full-fledged engraver or polisher generally takes around ten years.

When Miyazawa was starting out, the tasks were divided up, with veteran craftspeople handling the engraving and younger employees in charge of polishing and finishing. As such, he first mastered the polishing techniques before adding on engraving.

Ten years is a long apprenticeship. What makes the Edo chokin technique so demanding?

Miyazawa

The engraving is done by placing the chisel tip on the metal and tapping the end with a hammer, but if you tap too softly, you won’t get the desired effect, and tapping too firmly will soon wreck the blade.

To carve beautiful designs, you need to develop a feel for how much force is needed and at what angle the chisel should be applied, such that it becomes second nature.

What’s more, that feeling changes depending on whether you’re working with copper, iron, or another type of metal. That’s why mastering the technique takes a long time and many mistakes along the way.

An engraver must also use an array of chisels to carve their desired forms freely. For example, when working on the Phoenix emblem mold, Miyazawa says he used around 30 different chisels.

And since a chisel’s material requirements depend on the type of metal being carved, an engraver generally has some 200 to 300 in their arsenal. What’s more, they custom-make all of these tools to suit their own needs. Little wonder that becoming a full-fledged craftsperson takes a decade of practice.

What lies behind the phoenix’s fine feathering?

Koto Engraving and Miyazawa began working on the Century’s phoenix emblems with the current third-generation sedan, launched in 2018. The engraving workshop behind the second-generation emblems that appeared in 1997 no longer had personnel capable of carrying on the task.

Miyazawa

For me, working on the Century emblem felt like representing my country.

And because I was making the mold with techniques that trace back to Edo chokin, I was also conscious of the senior craftspeople who nurtured me and carried on the skills of past masters.

In any case, it was a special job, and gave me great motivation as a craftsperson.

Mold-making begins with the fabrication of a master mold by feeding the design data into numerically controlled machine tools. The resulting piece has its edges cleaned up with chisels, the shape corrected, and the surface polished to a mirror finish. Then Miyazawa uses his engraving techniques to hand-carve the fine features that could not be fully rendered in the design data, down to the phoenix’s feathers and individual scales.

Actually, before Miyazawa starts engraving, there is one other important step in the process. After coloring the master mold’s surface with a red marker, he maps out the design with a tool that resembles a fine-tipped pen. This is known as marking-off.

Initially, the Century’s designers requested a second-generation emblem reproduction. However, since craftspeople do all the work by hand—from marking out the design to chiseling and polishing—they can produce something similar, but not an exact replica.

Not only that, but when given the chance to craft a new phoenix emblem, Miyazawa was keen to make some updates of his own.

Miyazawa

When I saw the previous generation’s phoenix emblem, I was stunned by the exquisite artistry. That said, nearly 20 years had already passed since its debut in 1997.

The years transform the landscape and people’s values. I, therefore, wanted to add some changes in tune with the times—changes so subtle you wouldn’t notice them at first glance...

Miyazawa says the previous emblem struck him as bold and a little rough around the edges. By contrast, he quietly explains, he wanted to go for a more modern and refined look, making the feathering more delicate and adding order to the random scattering of heart-shaped scales.

Miyazawa began by putting pen to paper, redrawing the arrangement of scales and feathers on the phoenix’s body countless times until he was satisfied. Using the drawing as a reference, he then scribed the design onto the master mold.

With the marking-off finished, he could finally move on to engraving and polishing. While engraving, Miyazawa observes the chisel tip through a 20x magnification microscope, allowing him to carve incredibly fine details measuring one-tenth of a millimeter, or about half the width of a hair. This is finesse at its finest.

Similarly, in the polishing process, he refined the luster of the phoenix’s head, wings, foot scales, and other mirror-finish surfaces to make the whole more beautiful. If the polishing lacks precision, the reflection will appear distorted under fluorescent light. Miyazawa polished the mold meticulously to eliminate any hint of distortion.

With that, Miyazawa completed the first mold prototype for the Century’s designers to check.

Miyazawa

When I brought them the finished prototype, the designers asked me what I had in mind when I made it, and I answered that I wanted to create a modern version based on the previous generation.

They said, “It certainly comes across that way—you can put your ideas into the mass-production mold as well.” I was so pleased by this response, and it gave me the confidence to tackle the mass production mold.

A father and son’s enduring master-apprentice relationship

So, what considerations went into crafting the new Century’s phoenix emblem?

Miyazawa

With the phoenix emblem, the finish of the feathering, scales, and other minor elements can drastically change the overall impression. That’s why, just like for the sedan, I paid close attention to the details.

For the new Century, I made the heart shapes slightly larger than in the sedan, creating a more ornate feel.

“I strived for the highest possible quality so that it would look beautiful in anyone’s eyes,” says Miyazawa emphatically, finished emblem in hand. He was eager to share his accomplishments with the senior craftspeople. His expression brimmed with confidence and a sense of relief.

Miyazawa

I’ve heard that the Century’s development teams over the years have approached their carmaking endeavors with a philosophy of “inheritance and evolution.”

Every day, I also strive to continue evolving as an engraver and polisher, and I feel it is my mission to pass on the skills I have inherited from other craftspeople to younger generations.

In that regard, there was no greater pleasure than being involved in the Century project.

For Miyazawa, the pressing problem is “inheritance.” Aside from projects like the phoenix emblem, which require exceptional skills and aesthetic sensibilities, major advances in machine tools have drastically reduced the proportion of general metalwork that is now done by hand.

Seeking to pass on his inherited skills, Miyazawa assigned a small portion of the phoenix emblem work to Yumeha Sato, a junior colleague still in her 20s, as an opportunity to gain engraving experience.

Koto Engraving has also begun an initiative called Takumi Juku, inviting retired master craftsmen to teach their techniques to current practitioners. As a matter of fact, one such master is Miyazawa’s father, and Miyazawa himself attends Takumi Juku as a student to further develop his skills.

The Edo chokin technique has undergone several hundred years of inheritance and evolution. Even as the times continue to change, it will no doubt live on in the hands of proud craftspeople like Miyazawa, evolving alongside the Century’s phoenix emblem.