Kazushi Eto, clay modeling master. "The craft behind Japan's car making excellence."

While many people focus on advanced technologies such as 3D printing or AI when thinking about innovation, much of the work involved in car manufacturing is still done by hand.

In this series, by interviewing some of the masters supporting Toyota’s manufacturing with their craftsmanship, Toyota Times uncovers the essence and core strength built on traditional Japanese monozukuri (making things).

This is part two of our interview with master clay modeler, Kazushi Eto.

Series #7 Master Modeler Kazushi Eto gives shape to designers’ ideas in 3D

Chief Expert, Model Creation Section No. 1, Design Management Division, Vehicle Development Center at Toyota Motor Corporation

One of Toyota’s world-class clay modelers

Eto was assigned to the Model Creation Section of the Design Division in April 1992 and has worked as a clay modeler for 27 of his 29 years at Toyota. He has been in charge of developing everything from show cars to a variety of production vehicles, specializing almost entirely in exterior vehicle design.

In his 14th year at Toyota, he was assigned to be Modeling Leader for the first time in developing the 3rd-generation Vitz (currently Yaris) (2010 – 2020). He was also deeply involved in the exterior designs of the 8th-generation Hilux (from 2015), and the latest GR Supra (from 2019). All of these are models that have epitomized Toyota’s design through the years.

He has also worked as a modeling leader on a variety of other cars, helped develop the designs of new models, and as a coordinator also helps foster new clay modeler talent at Toyota’s design bases in the U.S. and France.

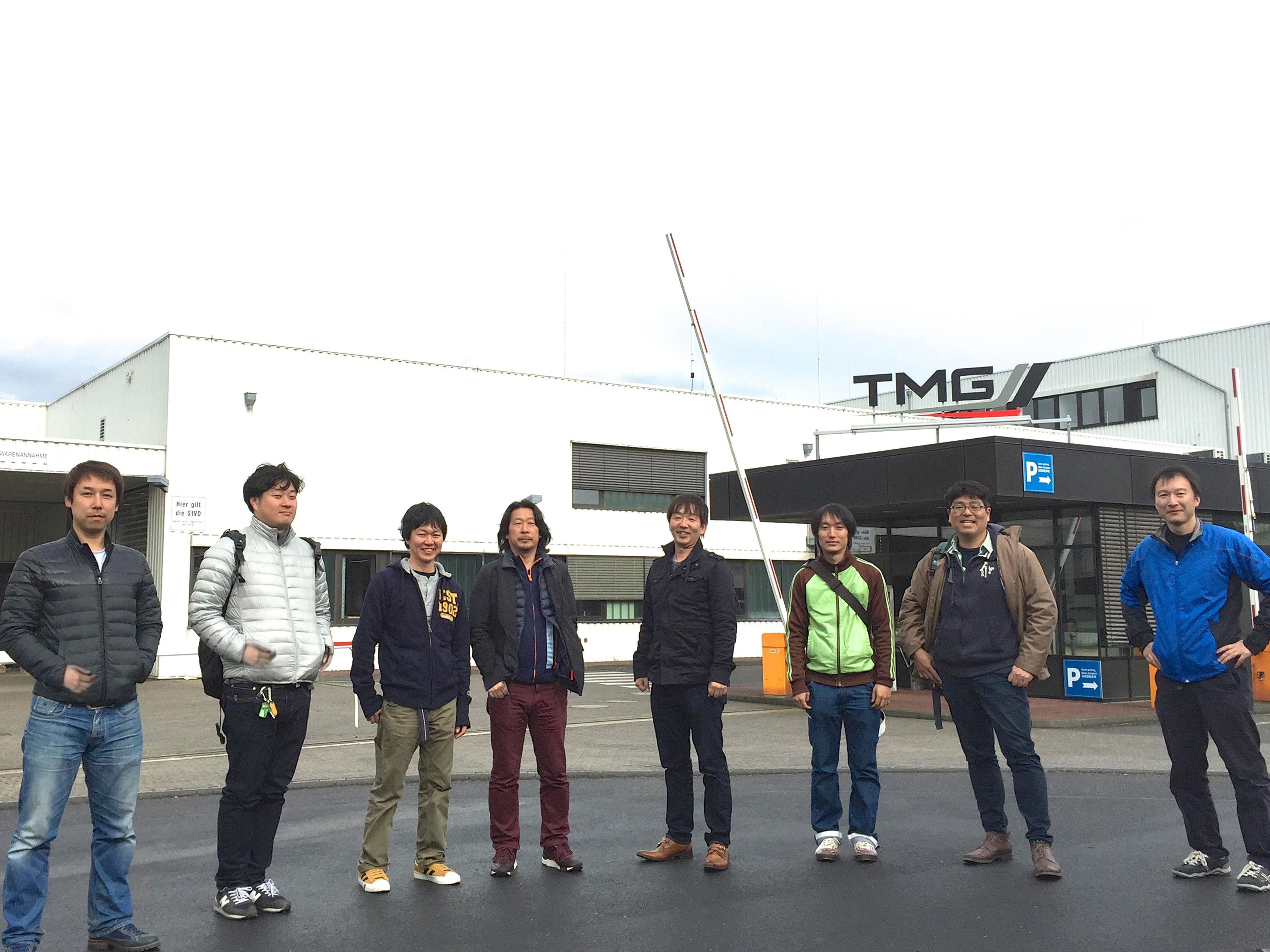

In 2013, he spent four months in eight European countries, including Germany and France, where he carried out a market survey to ascertain local design preferences to help in his clay modeling work.

“I realized that car bodies are often not exposed to a lot of sunlight in Europe, because the roads are narrow and there’s a high density of buildings. It was an eye-opening experience finding out, for example, that cars are designed to accentuate their three-dimensional shapes, with the upper surfaces of the hood and fenders reflecting the limited light to bring out the contours.”

From miniature scale models to full-scale

This article will once again focus on Eto’s work and skills as a clay modeler, picking up where part 1 left off. But first, let’s look at the history of clay models.

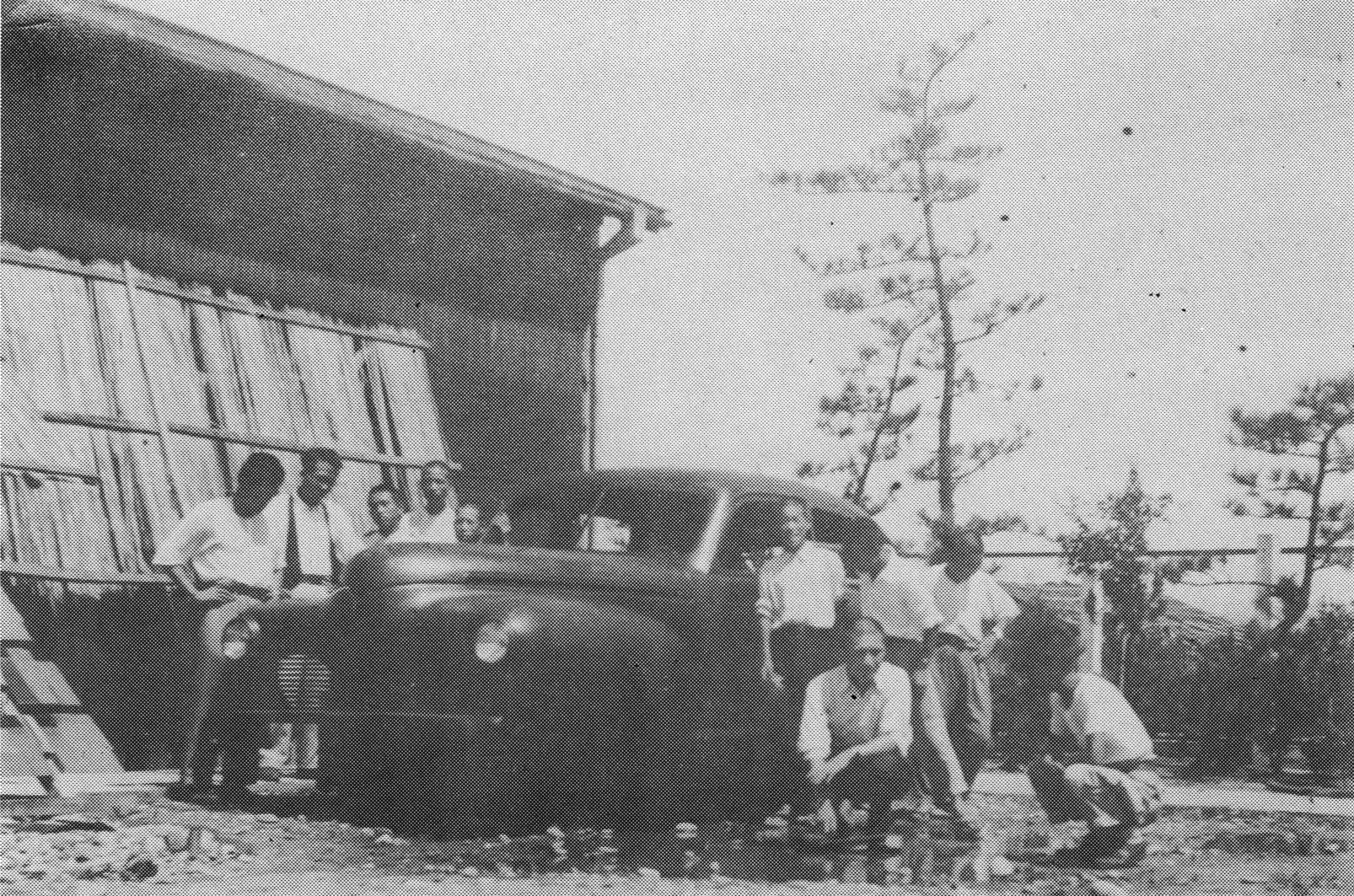

Toyota’s clay modeling began around 80 years ago, in 1942, with the making of the Model AL prototype. During the design process, it was difficult making a model out of wood because of its many curves. So, the company purchased oil-based sculpting clay (artificial clay made by mixing sulfur, wax, etc., with olive oil) to use instead, which meant designers could carve the clay or add extra freely.

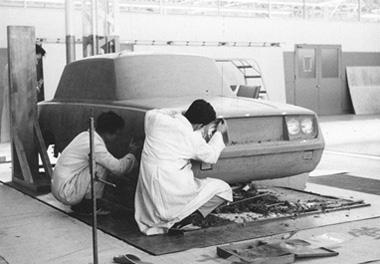

At the time, clay modeling already had a 40-year history in the U.S. The design team from Toyota studied American techniques and began using plasticine in 1960 as a substitute for oil-based clay.

“The biggest advantage of using plasticine was that it was easy to work with, allowing more clay to be added, or carved repeatedly at normal temperatures compared to oil-based clay. It allowed great precision in modeling the finest parts. You could also paint the surface for a more realistic finish.”

Eto continues, adding, “It’s thanks to research and model-making kaizen done by our predecessors, and the skills they passed on, that we were able to learn the techniques so that we could enjoy making models. I’m grateful for all their efforts and the history behind model-making, and I want to keep it alive.”

Incidentally, the 3rd-generation Corona (1962) was the first model at Toyota to be designed using industrial clay.

As mentioned in Part 1, Eto’s demonstration of concept modeling was nothing more than one of his jobs as a clay modeler in developing the design of a new car.

“The concept model is made strictly to give you an idea of the styling. It’s important to verify whether the design leaves a lasting impression, rather than trying to create a realistic design for a car. So, we sometimes intentionally ignore the overall balance to prioritize exaggerated features.”

Developing a car design also requires specific and practical considerations, such as its packaging. “Packaging” refers to the fundamental specifications of a vehicle, such as the number of passengers it can take, the seat positions, the layout of the engine, transmission, and other parts, and how spacious the interior should be. The exterior design has to be honed at the same time as decisions are made on the packaging.

The design must also satisfy the variety of safety standards for different countries around the world. Designers and clay modelers must hone their ideas through repeated trial and error while taking all these factors into account.

“We have to find a balance between our design concept and the various requirements of a car. I think the true test of a clay modeler’s skills is overcoming this through our experience, knowledge, and communication skills.”

A full-scale model in truth

Clay modelers use a plethora of sculpting tools and metal spatulas of all shapes when making clay models by hand.

“Toyota modelers have always made their own tools, so they could be customized to the size and strength of their hands. This gives them an opportunity to hone their instincts, pit their skills against one another, and acquire intuition for good monozukuri.”

The completed full-scale model is painted and fitted with realistic-looking lights and wheels to turn it into a high-quality model that is almost indistinguishable from the real thing.

Full-scale models in particular are an achievement made through unity among all the various engineers responsible for proposals, designs, planning and production, bringing together all their best ideas. Requests from engineers are fed back to the designers, as is the knowledge of sales functions representing each market, and adjustments are made while making sure the original idea is not compromised.

“Designers often claim it’s a major role of theirs to determine the shape and commercial value of the car. The advantage of making clay models is that they allow you to see and touch the model with your hands, to verify the pros and cons, and commercial value, of their designs.”

“Clay models are also shown to our senior management so they can verify the direction we’re heading, and take an active part in our car design process.”

A design meeting is the final step, and the car’s development for mass production starts once it gets approved.

Beautiful contours created by delicate tools

Eto gave a live demonstration to show just how delicate and difficult it is to make full-scale models, and how skillful clay modelers are.

The beautiful curve of the rear fender of the GR Supra clay model was damaged, then restored for this demonstration.

At the start, he heated some clay to soften it, then applied it carefully to the fender to make the general shape. But even this one process is not easy when you actually try it.

He blended the fresh clay into the rest of the body and smoothed out its shape using tools. Then he used a metal spatula to make the finishing touches. With a light, soothing sound like that of a master carpenter working a plane to finish a piece of wood, Eto quickly restores the fender to its original beautiful and perfect shape.

Toyota Times staff also tried their hand at using a metal spatula for modeling, but ended up leaving a long scratch with the corner that ruined the surface.

“I try to imagine the curve of the finished fender as I bend the spatula with the tips of my fingers to adjust its curvature,” explains Eto. The spatula curvature has to be controlled while simultaneously adjusting the pressure on the clay surface. This requires an extremely subtle touch.

Eto says he can tell whether the curve of the body is right by just looking at the light reflected off its surface. He also relies on his sense of touch to check for subtle distortions on the surface of the fender by stroking it with the palm of his hand.

For this demonstration, Eto used different-colored clay to make it easier to see the restored area. But touching the area with your fingers reveals how it has smoothly blended into the rest of the body. It testifies to Eto’s true artistry.

An educator with knowledge of real and virtual technologies

Digitalization of the work of clay modelers is advancing at breakneck speed, just as it is with other departments involved in developing cars.

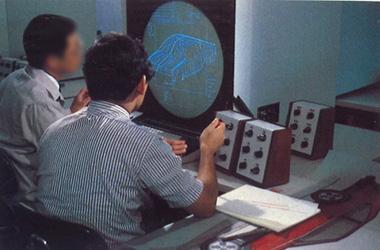

Toyota has always been eager to digitalize its design development technologies. Clay models are measured and digitalized, then turned into blueprints using CAD software. This method was already being used back in the 1970s, and equipment to follow data in processing clay models placed on a surface plate has been used since the 2000s.

Eto himself experienced developing designs digitally in the early stages of his career. In the latter half of the 1990s, he left clay modeling for three years and became involved in designing products using CAD. This gave him an excellent understanding of the pros and cons of digitalization.

“I’m currently working on practical digital modeling use. It has the advantage of allowing rough shapes to be made quickly. You can choose an idea from several shapes, which makes the process very effective.”

Eto has this to say about the current state of digital modeling:

“Some people think digital modeling allows cars to be designed easily on a computer, but that’s not the case. When you create a model from data using a 3D printer or similar machine, it often turns out to be very different from what you imagined.

We’re continuing our efforts to hone the capabilities of both people and equipment to try and minimize this kind of discrepancy. There’s not much point in digitalization unless you can make others feel that you’ve designed a cool car. That’s what I place the greatest priority on—an area where I can’t make any compromises as a designer.”

There are special things in life that you can only perceive through all the senses – something that you can only experience by seeing the real thing with your own eyes, and touching it with your own hands.

Eto continues, “We have to focus on Toyota’s monozukuri principles inherited from our predecessors, of concentrating on production and boosting efficiency, while taking advantage of the merits of both digital and clay modeling to establish our own style.”

He also claims that clay modeling retains the fun and joy of monozukuri, allowing you to make things with your own hands.

“The true joy of monozukuri lies in striving for absolute perfection right to the end, and that’s what modelers pour their hearts and souls into. We have to pass on our clay modeling skills to future generations until the day comes for digital modeling when people will say with surprise, ‘This design is so meticulous; you really didn’t make this on a clay model?’”

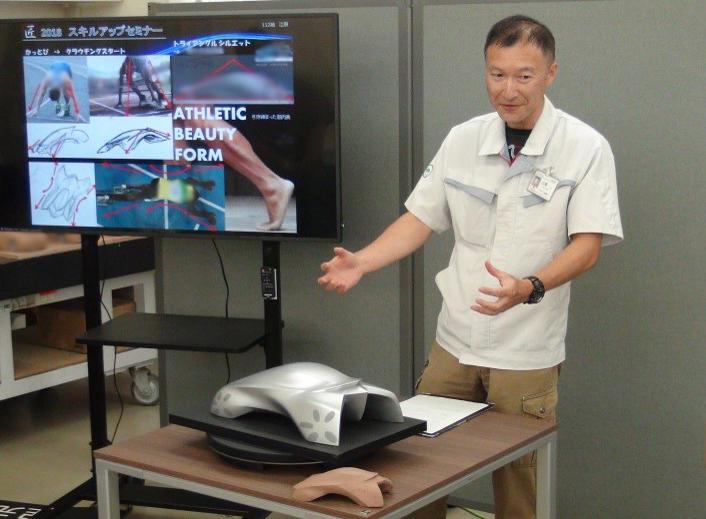

Eto is now working as an educator, running workshops known as “modeling seminars,” through which he teaches skills to car modelers both in and outside the company. His aim is to make sure that real monozukuri skills continue to live on in the future in the face of further advances in digitalization.

“I may be teaching, but I’m actually learning a lot from my trainees too. We have to overcome our generation gap and continue growing through mutual respect. You’re done for as a modeler if you stop growing.”

“There are definitely very talented digital modelers too. I expect they will push digital modeling really far, but no matter what happens, there will always be a need for car models which resonate with people on an emotional level.

The way they are designed, the materials used to make them, or the set of skills needed to be a car modeler may change. When that happens, they may no longer be known as ‘clay modelers’. In that way, there are always new discoveries to be made in car modeling. It’s a stimulating, fascinating, and profound job, but above all, it’s a job that holds so many possibilities for the future.”

Eto’s journey continues as he heads into the future of car modeling.

(Text: Yasuhito Shibuya, photo: Akira Maeda)