Toyota's Plants: Inheritance & Evolution is a series introducing the history and future vision of individual production facilities. This article focuses on the Honsha Plant's current situation and the challenges it is undertaking for the future.

At the forefront of Toyota’s efforts

This new series, Toyota’s Plants: Inheritance & Evolution, will delve into the unique character of each facility, highlighting its history up to the present as well as its vision for the future.

As we saw in the previous article on Inheritance, the Honsha Plant’s mission is to handle the “phase in,” which means venturing into uncharted territory ahead of other facilities. The plant brims with the culture and skills to tackle new mobility challenges, from making the fuel cell stacks at the heart of the Mirai to planning production for large battery packs for BEVs.

It also serves as a “global mother plant,” providing overseas facilities with expertise, including the forging and welding technologies that have been honed here since doors first opened in 1938.

For this article on the Honsha Plant’s Evolution, we zoom in on four of its divisions, thoroughly dissecting their genba atmosphere and future-focused initiatives.

[Forging Division] Specialists in steel and heat

Let’s start things off with the Forging Division, “a group of specialists in steel and heat” that has been around since the plant was founded more than 85 years ago. The division produces nearly 200 different components, chiefly engine parts.

Forging involves using a hammer or press to beat metal into the desired form. Dating back more than 6,000 years, it is regarded as humanity’s oldest metalworking process.

The Honsha Plant’s Forging Division mainly employs a method known as “hot forging,” in which steel is softened by heating it to around 1,250ºC and then shaped by a press.

Working steel through hot forging requires strict temperature control. Too much heat risks melting the material; if the temperature is too low, the steel remains hard and cannot be shaped as intended.

The need to closely monitor even subtle changes in temperature makes forging “a difficult realm to digitize,” says Hiroshi Tonozono, a project manager within the division.

Hiroshi Tonozono, Project Manager, Forging Div.

Forging is a difficult world to digitize. Machines can only be substituted in because they are accompanied by human skill.

As well as bringing in new machinery, we must also preserve forging that uses human senses—being able to tell the temperature by looking, pressure by listening, abrasion by touching, and deterioration by smelling. Unless we nurture individuals who instinctively understand what makes for good or bad forging, we won’t be able to build a new future.

The challenge is figuring out how to incorporate these skills into the machines. By its nature, forging requires you to be attuned to slight changes in the day’s temperature and to make the necessary adjustments.

To nurture “individuals who instinctively understand what makes for good or bad forging,” the Forging Division deliberately retains processes that involve seeing, touching, and working steel with human eyes and hands.

The division is currently working on forging aluminum parts as a way to reduce the weight of BEVs, which are heavier than ICE cars.

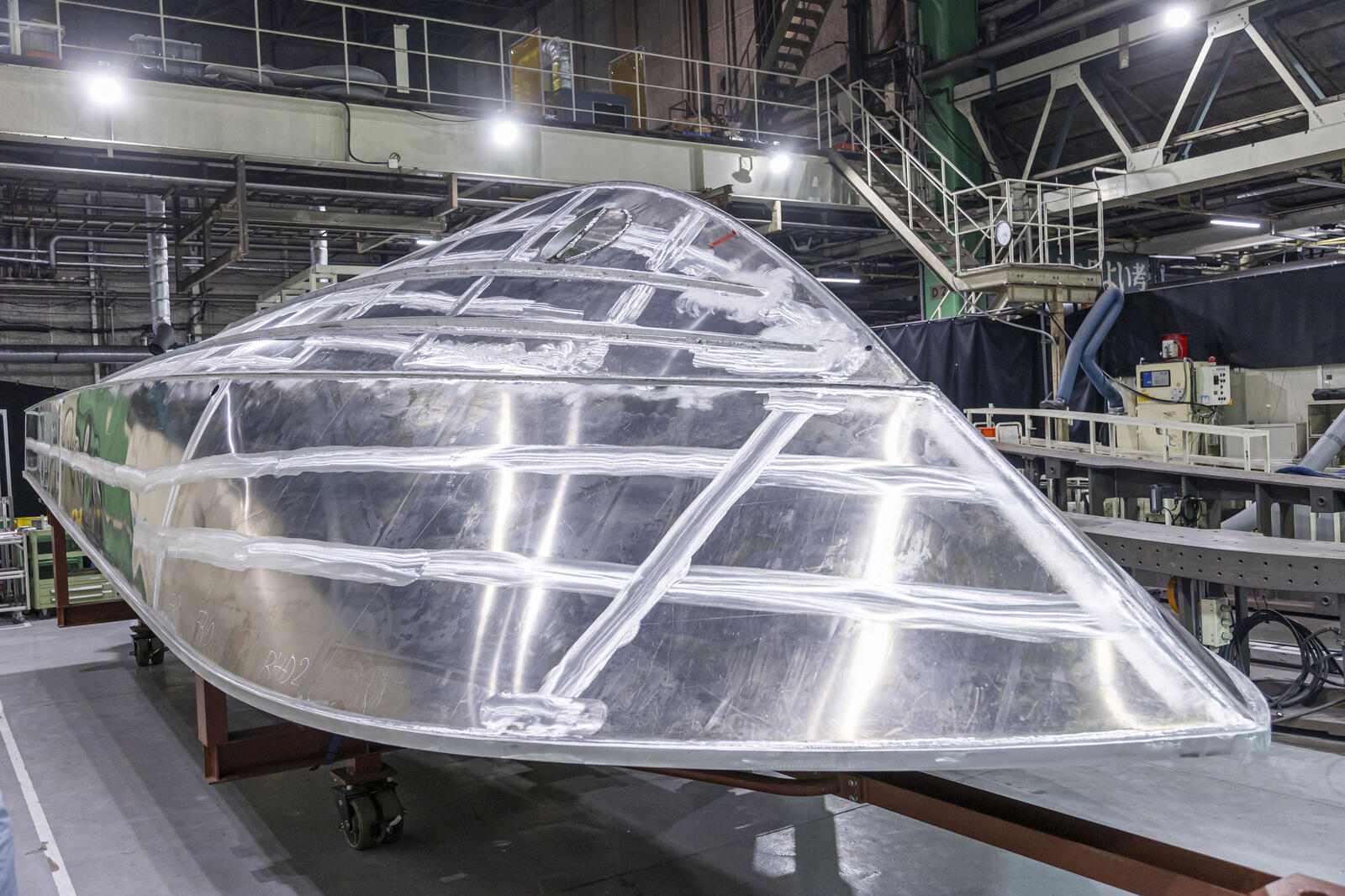

To gain expertise in working with aluminum—which differs from steel in aspects such as strength, optimum temperature, and stamping conditions—the team is making use of the hulls for Ponam-31 boats, which Toyota makes as part of its marine business.

Aluminum hulls offer the advantage of absorbing wave impact and reducing vibration, making for a more comfortable ride.

Though fabrication was originally outsourced, the Ponam-31’s popularity pushed orders to the point where customers had to wait more than a year, and Toyota decided to boost production capacity.

The Honsha Plant took up the task, with the Forging Division putting its hand up to produce the hulls, gaining valuable aluminum expertise in the process.