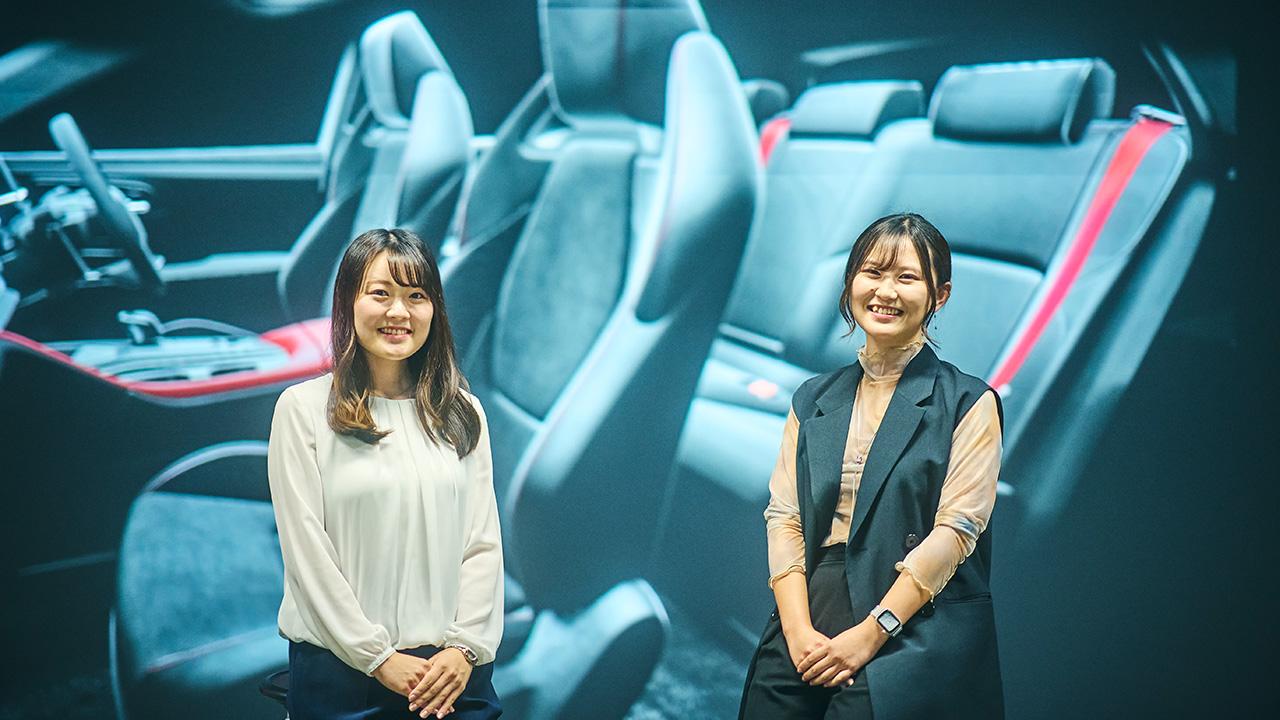

The Crown Sport was recently unveiled as "a new form" of sporty SUV. Members of the model's development team talk about the various challenges undertaken in the name of making ever-better cars.

Fail once, fail 700 times…

To give the car its visual “wow” factor, designers focused in particular on the rear fenders.

Yukihiro Koide served as the lead for the Crown Sport’s exterior design. He says the team strove for an exhilarating design with a silhouette that embodies the car’s agility.

Koide

Together with the Crown Sport’s large 21-inch tires, we wanted the rear fenders to convey the power behind those wheels.

While a standard feature of car design is adding a character line along the side, with the Crown Sport, we opted instead for a dynamic effect that engages people on an emotional level through the body's curvature alone.

The prominent profile of the rear fenders is unlike anything found on past Toyotas. Koide explains that streamlining the rear of the cabin (the side windows above the rear fender) and the side body (around the rear doors) created an even more powerful impression than the fender’s profile alone.

Koide

With that rich body curvature, the car presents different aspects as the light shifts while in motion, which is truly stunning. That’s what gives the Crown Sport its uniquely exhilarating elegance.

This design was made possible by our production engineering members.

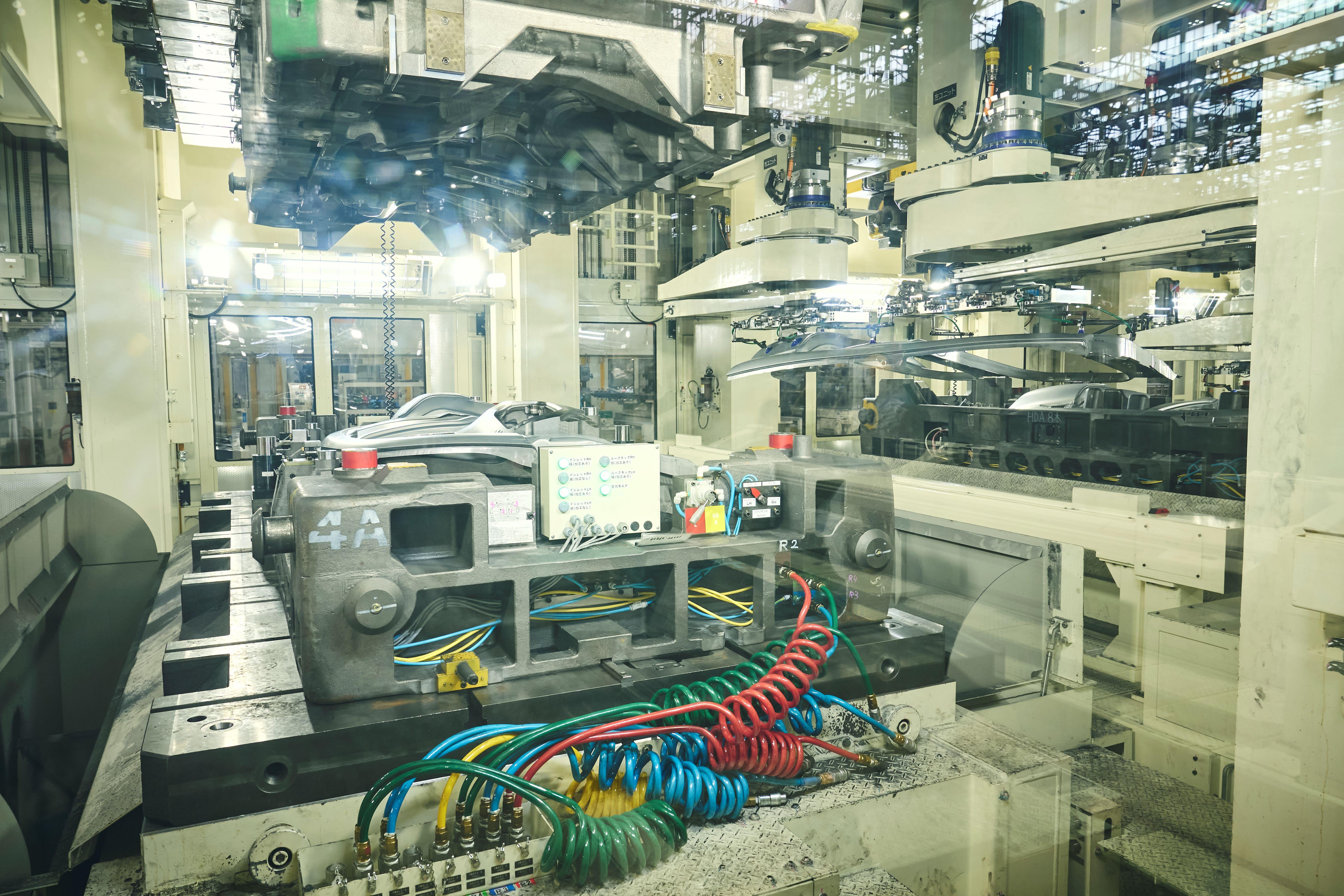

Kosuke Fukuda was one of those production engineers involved in the new Crown project. Ever since joining Toyota in 2016, he has worked in what is now the Productization Production Engineering Division, designing molds and technology for stamping rear fenders.

Fukuda

My job is to devise stamping molds for vehicles in development, working with the designers to figure out which production methods will work best for creating a given design.

I’m normally involved up up to the point of designing the molds. Still, the Crown Sport presented so many challenges that I stayed on after the molds were fabricated to look after everything from mass production assessment to the start of manufacturing.

In this line of work, Fukuda’s trusted partner is Atsushi Soba.

Achieving the rear fender’s beautiful contours requires an extremely high degree of precision, meaning the molds had to be identical to the design data. The process entailed eliminating body distortion by removing or adding material to the mold through grinding or welding and other adjustments to make the panel more precise.

Soba is a mold specialist who handles such tasks.

He joined Toyota in 2007 and spent his first two years as a National Skills competitor, honing his talents in finishing molds by sanding. In 2009, Soba transferred to the Mobility Tooling Division that fabricates molds, where he has since been responsible for fine-tuning.

Soba

Having worked exclusively with molds, when I first saw the Crown Sport’s rear fenders, I was struck by how deep they are.

Production engineering staff like Fukuda usually join a project only once the exterior design is more or less set. To turn this challenging design into reality, however, Koide wanted to share the designers’ vision and direction as early as possible and had Fukuda view the 1/1-scale clay model while it was still being shaped.

Fukuda

The clay model looked so cool when I first saw it, and I was ready to do whatever it took to bring that form into the world. But, honestly, I felt that making it happen would be quite difficult…

The more a body part protrudes outwards, the more the panel needs to be shaped. This can concentrate stress in certain sections of the panel or disperse it, leading to distortion or cracking. To begin with, any increase in the amount of shaping makes it harder to maintain a clean surface quality.

Fukuda

We designed molds on our computers using a 3D CAD (Computer Aided Design) system and tested them in simulations, but we just couldn’t get them right.

The trial-and-error process involved some 700 failed attempts over the course of four months, by which point I was losing heart.

The breakthrough came with this advice from a supervisor: “Don’t be afraid to let loose.”

Fukuda

As engineers, we have certain ideas of how equipment should be used or what molds should look like.

To be told by a supervisor that I could set these ideas aside, be more flexible, and challenge myself to use equipment and move molds in ways I hadn’t before—that really made me feel more at ease.

As he continued to try new approaches, Fukuda came up with an innovative method.

In the stamping process, a panel is generally formed by pressing the material against a stationary mold. Yet in simulations, Fukuda found some success by moving the mold slightly to ensure that the material inside the press was ideally formed.

However, this necessitated the extremely difficult task of coordinating mold movements within a process that lasts 0.7 seconds. Fukuda and his colleagues made a test mold and trialed it on the press to see if the new method would work like their simulations.

Fukuda

As expected, the test pressing yielded many defects. To solve them, we had to adjust the mold down to thousandths of a millimeter, and for that, we needed the skills of a master craftsman like Soba.

We refined the finished product by tackling each defect with a technical engineering approach and the quality of our skilled craftspeople.

Soba

Among the members of our department involved in the Crown Sport project, I think I messed around with those molds more than anyone else (laughs). I would spend a week continuously adjusting the same spot.

Personally, getting the chance to adjust and refine these molds was a wonderful experience.

In this way, the Crown Sport’s prominent rear fenders came to life. Koide brims with emotion as he remembers being “really moved” when he laid eyes on the first prototype.

Koide

I was ecstatic to see that the prototype came out exactly as we, the designers, had envisioned.

I feel that we achieved this design by coming together across department lines to tackle obstacles as one team.

Fukuda

Rather than compromising on account of the difficulty, harnessing technology to make something happen is the ultimate joy for an engineer. This experience has inspired me to continue challenging myself in other projects as well.