A special project team worked on reviving a Toyopet Racer, Toyota's first racing car from over 70 years ago. This article focuses on the struggles of I-beam forging.

This series features Toyota’s project to revive a legendary racing car—now on display at the Fuji Motorsports Museum—with a look at the project members’ efforts as well as the history and meaning behind the vehicle.

In this sixth article, Toyota Times catches up with the team that produced the I-beam, a major component in the car’s front axle and one of the project’s key monozukuri (manufacturing) challenges. Part 2 tracks the forging process.

Determined to make the I-beam using the original methods, Miki and Toya came across a company publication entitled “Toyota Motor Corporation – 50 Years of Forging in Pictures.” It included a chapter on die-forged front axle I-beams for light trucks, with text and images describing how such parts were once produced. This inspired the two-man team to attempt the forging techniques used in the days of the racer.

Just too big

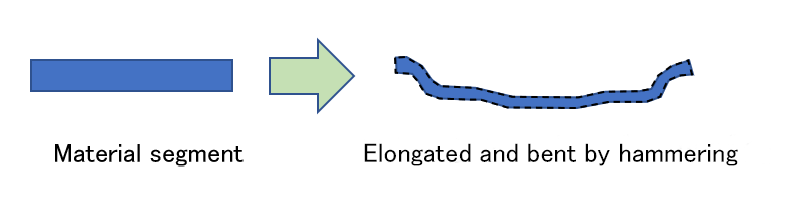

First, the initial shaping was to be done by a method called hammer forging. Round segments of the base material are cut to the specified length, then heated in a furnace. The red-hot pieces are then struck by a pneumatic hammer to elongate and bend them into the I-beam’s complex shape.

Toya

From my plant induction as a newcomer, I knew that our Forging Division was equipped to handle hammer forging. I went back to my group leader and plant manager from those early days to see if they could create the required I-beam shape using the original hammer-forging method.

Unfortunately, the Forging Division has no recent experience hammer forging such large pieces. The job of coordinating this difficult task fell to Toyohisa Manabe.

Manabe joined Toyota in 1991. As a project manager at the Engineering Service Department’s Drivetrain Forging Group, his work involves maintaining, improving, and reducing the costs of forging line production. Throughout his time at the company, Manabe has excelled as an engineer working with forging-related production technologies and manufacturing divisions.

Manabe

The biggest challenge was the size of the I-beam, which is around 130cm long. We don't have the facilities to forge parts larger than one-meter in-house. So, we had no choice but to go outside the company for the die-forging process after we finished hammering. I told them we could not do everything in-house.

For these reasons, Manabe explained that if the parts were to be finished to their final form in-house, they had to be a bit smaller in size. Toya and Miki, though, were committed to using the old methods for the I-beam.

Miki

No matter what, we wanted to make that impressive I-beam we had seen on the SG truck, so we couldn’t settle for less. We went back to Manabe and asked if it could be done by bringing together current manufacturing capabilities, both inside and outside the company.

Thanks to Manabe’s efforts, the finishing work was taken on by Riken Forge, which produces forged parts for Hino Motors. In a somewhat unusual process, Riken Forge would handle the die-forging work using ten of the hammer-formed pieces and the molds (Part 1) created at Toyota. Outsourcing some of the process meant less freedom in prototyping and making adjustments, and there were no guarantees about the quality of the end product. Even so, Miki and Toya had found a partner who shared their commitment to monozukuri.

Meanwhile, the task of hammer-forging material into the base shape also proved difficult, requiring a very high level of accuracy. To manufacture parts with complex shapes like the I-beam, generally at least two molds are prepared – the first to create an approximate shape, which is then completed in a second, finishing mold. This time, however, the team would have only a finishing mold.

Toya

Initially, we were advised that two molds would be necessary, but looking through “50 Years of Forging” we deduced that the shaping was done by hammer forging.

If someone had done it before, we figured that the Toyota of today should be able to do it too. We spoke with Manabe, and he took on that extremely difficult shaping challenge.

Veterans tackle uncharted territory

The daunting task of shaping the I-beam using hammer forging alone was undertaken by veteran technicians at the Forging Division. Even for them, the job was harder than anything they had experienced before.

Hammer forging normally involves three people: a “positioner” who holds the material being shaped and directs the hammer operations, a “hammerman” who operates the hammer according to those directions, and an “assistant” to open/close the furnace and check the formed dimensions. The long and heavy I-beam, however, required an extra assistant to carry it, bringing the total to four. Because the material must remain hot to allow shaping, the positioner moves it repeatedly between the furnace and the hammer. Thorough safety controls are necessary due to the high temperatures of both the equipment and material.

Serving as positioner for the I-beam hammering work was Yoshifumi Fujinaga, who has been with Toyota since 1977. Despite having already reached retirement age, he has stayed on to teach younger staff as a forging skills trainer.

Fujinaga

Above all, the size of the material being shaped meant that, even for us, this work was uncharted territory. Of the roughly 130cm-long piece, the hammer can only strike a section of about 30cm, so getting the dimensions right is a Herculean task. We approached it as a team, pooling our expertise to see what we could achieve.

One of those who assisted in transporting material and checking dimensions was Hirohito Nakane, who joined the company in 1979. A senior expert in heat treatment, like Fujinaga he is now also a trainer sharing his skills with junior employees.

Nakane

We only had some of the necessary measuring instruments for checking whether the finished shape and size were correct. It became a matter of hammering, repeatedly checking the shape and dimensions with our makeshift measuring devices, and then putting it under the hammer again. The work is dangerous, so we used signals to make sure everyone was in sync.

The hammerman on this occasion was Masaharu Okamoto, a 32-year veteran of the Sintering and Forging Division. Along with serving as a sintering and forging trainer, he is a senior expert passing on the skills of a hammerman to younger generations.

Okamoto

I was a hammerman for around six years, and much of the work relies on instinct and experience. This was the largest part I have ever made, so completing it brought a great sense of accomplishment.

Fruits of passion and persistence finally ready for finishing

Along with the molds showcased in Part 1, the ten pieces hammer-forged with the help of Toyota’s veteran technicians were then sent to Riken Forge.

With Miki and Toya looking on, at last, Riken Forge began the final forming process.

Unlike the hammer forging and mold-making, they expected the finishing work to go smoothly, but things did not turn out as hoped. The problem was “underfill,” in which the material does not completely fill the mold, resulting in the final shape being incomplete.

Miki

As six, then seven defective beams piled up, I began to get a little worried, but this was just a matter of the order, with the hammer-forged pieces getting more precise as they went. All we could do was pray, but I convinced myself that it would be alright.

Toya

If this didn’t work out, we would have to modify the mold, which could require a lot of extra work. We might also need more of the hammer-forged pieces the Forging Division had so painstakingly made for us. Working with the Riken Forge team, we desperately tried to figure out our options.

To prevent underfill, the hammer-forged pieces must be set correctly in the mold. If this process takes too long, however, the temperature will drop, leading to an undesired amount of heat shrinkage and a finished part that is not the intended size.

The team got around this problem by revising their process. Pieces were placed in the mold, stamped several times, then reheated before being processed to the final shape. Combining these improved processes with a more precise input piece, the final I-beam—carrying the hopes of everyone involved—emerged from the forge in the perfect shape, with no underfill.

With the forming process complete, the I-beam was machined to prepare the surfaces and holes for assembly onto the vehicle. Finally, Miki and Toya installed it onto the Toyopet Racer.

Reflecting on the revival

Miki

Personally, I think we were able to produce a perfect I-beam that ticks all the boxes in terms of showcasing the outstanding manufacturing of its day. From the project team members to the restoration professionals at Shinmei Industry, everyone was impressed when they saw the finished part. I would like to once again thank all the people, both at Toyota and beyond, who shared our passion and worked with us to make this happen.

The fact that we can tackle these kinds of projects is also thanks to the pioneers who established Japan’s automotive industry. As the industry faces a once-in-a-century transformation, we too will continue to take on the challenge of shaping the future.

Toya

In the beginning, many people told us it couldn’t be done. But we did it. I’m truly grateful to everyone who did believe it was possible, and worked tirelessly with us toward that goal. We are here today because of the hard work of those who came before. Likewise, we have a duty to do the same for future generations. Whenever I think back to the I-beam, my passion for car-making is reaffirmed. As I continue my work, that is a feeling I don’t want to forget.

The next article in this series spotlights the challenges of producing another key component – the seat that supports the driver’s body.

(Text: Yasuhito Shibuya)