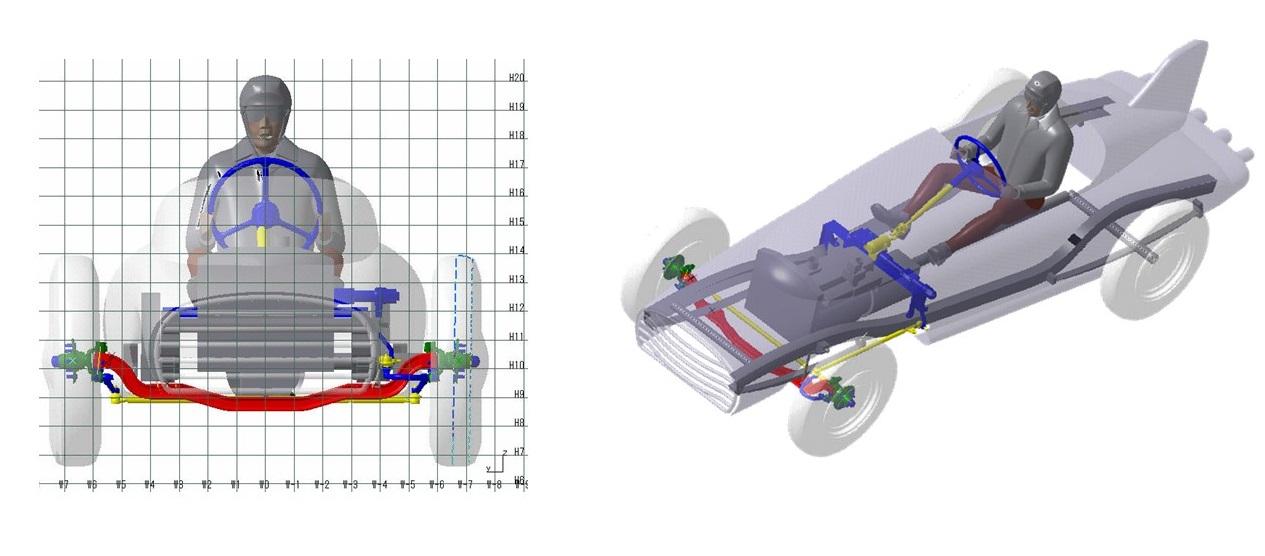

A special project team worked on reviving a Toyopet Racer, Toyota's first racing car from over 70 years ago. This article traces the challenge of creating I-beam molds.

This series features Toyota’s project to revive a legendary racing car—now on display at the Fuji Motorsports Museum—with a look at the project members’ efforts as well as the history and meaning behind the vehicle.

In this sixth article, Toyota Times catches up with the team that produced the I-beam, a major component in the car’s front axle. Part 1 focuses on the process of producing metal molds by hand.

Two team members with a hunger for car-making

In reviving the Toyopet Racer, of which only two were built in 1951, one of the project’s main goals was to impart the skills, techniques, and spirit of Toyota’s pioneers.

The team therefore adopted a basic principle of building parts using the original methods wherever possible. Trying these methods for themselves let the team members gain a better appreciation for the vision of Toyopet Racer creator Kiichiro Toyoda and others involved in the making of this machine, ensuring that their skills and techniques are passed on to future generations.

For the pair in charge of fabricating the front axle—Reisa Miki of the MS Electronics System Engineering Division and Suguru Toya from Production Engineering—this guiding policy led to some challenging decisions.

Miki graduated from a technical college in Shizuoka Prefecture and in 2011 joined a Toyota affiliate that became part of Toyota Motor Corporation in 2015. Toya also joined Toyota in 2011 after graduating from technical college and then obtaining a university degree in mechanical engineering. Both are born car lovers who tinkered with cars and motorcycles for fun.

In their everyday work, Miki’s job involves digitizing the development process for car wiring harnesses, while Toya went from developing technology for efficiently making part molds to controlling manufacturing equipment for electric vehicle components. These roles gave them few chances to be directly involved with cars, and both were eager to get stuck into car-making. For Miki and Toya, the revival project presented a perfect opportunity to satisfy that hunger.

Miki

I applied just as soon as I got the email announcing the call for members. I had already put my name down by the time my supervisor suggested I might like to join (laughs)! As a fan of historical dramas like “Leaders,”*1 which was based on Kiichiro Toyoda, this felt like a once-in-a-lifetime chance to not only be involved in building a car, but also to experience the history of Toyota.

*1 The first season of “Leaders” aired in 2014 and the second in 2017 in Japan.

Toya

I didn’t know about the Toyopet Racer until the call came for project members from our division. I was so excited by the chance to be directly involved in car-making that I immediately applied for the project—I did not want to miss out.

Building an I-beam by hand

Miki and Toya were tasked with reviving the racer’s front axle and steering. When the assignment came, their first port of call was a surviving Toyopet Model SG Truck on loan from the Toyota Automobile Museum. Inspecting the truck, they were drawn to one part in particular—the 130cm-long I-beam that was a key component of the front axle.

The I-beam is part of the suspension system and subject to tremendous forces during driving, so the molding process involves heating and hammering the raw material in a mold to increase strength. Parts created by forging are not only stronger but also have a unique presence that captivated Miki and Toya.

Miki

The irregular surface that comes from forging gives it a real sense of mass, and above all, the beam plays a key role in supporting the left and right axles. Looking at the Model SG Truck front-on, the I-beam is very prominent. The moment I saw it I thought, “This is the part we’re going to pour all of our passion into!”

Toya

The Toyopet Racer itself has a wonderful story. And within that, we want to weave our subplot of “monozukuri (manufacturing),” which will hopefully give those who see the car more to enjoy. To do that, we felt we had to make the I-beam in the same way it was originally done.

To make the I-beam using the original methods, the pair had to research the skills and techniques that were involved. In this quest, Miki and Toya enlisted the help of specialists at the Vehicle Development Center, Production Engineering Development Center, and Forging Division.

The pair also visited the Toyota Commemorative Museum of Industry and Technology in Nagoya to learn how mold-making and forging were done in the days of the Toyopet Racer.

Nowadays, molds are essentially cut by computer-controlled machines, with additional grinding if necessary. When the racer was made, however, the process involved shaving material away by hand with a chisel and hammer, then grinding the surface to the desired finish before hardening with heat treatment.

Miki

Hand-carving a lump of metal?! Now that grabbed my interest. I decided on this method because it was a rare chance to work with my hands.

Toya

I had experience with developing cutting technology for molds, so I knew this would be different from carving wood with an engraving knife. Of course, it turned out to be much more than I had imagined...

At this point, the pair ran into a big problem. Having decided on their production method, they discovered that the costs would eat up over 10% of the project budget. This would make the I-beam the priciest part of the entire car.

Miki and Toya held discussions with other project members to gain approval for the budget allocation. After several hours of debate, the pair’s passion won out, giving them the green light to proceed.

Miki

I think those were the most heated discussions in the course of the project. Since everyone had given us permission, I felt we had to do them proud by creating an excellent part. Failure was not an option. This episode fired up my passion for the revival even further.

It’s up to us now

Miki and Toya looked for people to assist them in making the mold. Despite approaching several departments, and even going outside the company, they could find no one with experience in hand-carving molds. They were also told that their short time frame was unfeasible. In the end, the challenge was taken up by Tomohiro Miura, a colleague of Toya’s in the Production Engineering Division.

Miura

You could see in their faces and hear in their voices that they were set on trying to make it the old-fashioned way. When I heard what they wanted to do, it felt like a once-in-a-lifetime chance to put our skills to the test. I agreed on the spot and told them, “If we’re the only ones who can do it, then we’d better do it!”

Kawano

I said to Toya, “You should have come to us from the beginning.” Personally, I’m happy they feel they can turn to us with a specific job, and if one of my team members puts their hand up that’s all I need.

Sore hands and arms like lead

Miki, Toya, Miura, and five others from the Production Engineering Division set about making the mold with hammers and metalworking chisels. What did this shaving process actually involve?

Miura

This shaving technique is a lot about instinct and getting the knack for it, so it’s really difficult to teach. The only way to learn the ropes is by watching how it’s done.

We spent about ten days on the shaving process alone, and by the end of it, everyone’s hands were sore and swollen. In that time, we scraped out about 4-5kg of material by hand. To make the work fun, we made a game out of guessing how much the shavings would weigh in the end (laughs).

Miki

If you try to shave off a thick layer, the chisel gets stuck because the material is too hard. If it’s too thin, the shavings quickly break off and you can’t keep a consistent line. As I went through this trial and error, I could see Miura tapping his chisel with a steady rhythm and shaving away evenly. It really brought home the difference in skill compared to a real craftsman.

Toya

In the past, people must have worked incredibly hard in environments that were far harsher and more demanding than today. I tried to imagine those bygone production floors while doing the shaving work. By the time I was done, my hands were so numb and tired that I could barely hold the soap bottle as I tried to wash up.

It was tough work. Yet above all, those involved were thrilled to see their skills improving day by day. The team members look back fondly on the task they were able to complete together.

Working in turns, they eventually managed to complete the shaving process.

Tempering and finishing complete the mold

After being hand-shaped by the team, the I-beam mold was tempered to harden it, then finally finished by hand.

Miki

During a difficult time for business, Toyota’s pioneers relied solely on their skills to carve out a future. Seeing the work of true craftsmen up close reaffirmed the importance of honing one’s skills to a professional level. I want to put this experience to good use in my regular work.

Toya

Advances in technology mean that manufacturing today is immeasurably easier than it was in those days. For that we can thank everyone, both at Toyota and our partner companies, who continued to build on the technologies that came before. We are in a position to enjoy the benefits of that history. This is something I felt strongly through the project.

The second part of this article showcases the efforts of project members who, together with the Honsha Plant Forging Division, worked to mold the material that would become the I-beam.

(Text: Yasuhito Shibuya)