This is an ongoing series looking at the master artisans supporting the automotive industry. For our 23rd installment, we spoke to a master of materials research who contributes to Toyota's ever-better carmaking by deciphering the sectional structures of various materials, from metals to plastics.

Handwork still plays an important role in today’s car manufacturing, even as technologies like AI and 3D printing offer more advanced methods. This series features the craftsmanship of Japanese monozukuri through interviews with Toyota’s carmaking masters.

In this two-part article, we shine the spotlight on master materials researcher Mitsuo Takano, who supports vehicle design and development by deciphering the sectional structures of various materials, from metals to plastics and ceramics.

#23 Mitsuo Takano, the master materials researcher who deciphers material structures

Takumi, Grand Expert (GX), Mobility Material Engineering Division, Advanced R&D and Engineering Company, Toyota Motor Corporation

Mastery of 0.02 microns

In the Materials Research Lab inside Technical Building 5 at Toyota Motor Corporation’s head office in Toyota City, Mitsuo Takano gently presses a metal cross-section against a rotating felt buff.

The buff is coated with a slurry of fine aluminum oxide particles, often called alumina, in water. Through the polishing process, these tiny particles, no bigger than 0.02 microns (0.00002 mm), allow Takano to hone the metal surface to a mirror-like finish.

Takano

I’m barely resting my hand on the piece.

As Takano explains, he slowly turns the material while allowing it to make contact with the buff through its weight alone. Applying pressure with his hand would cause the nap of the rotating buff to leave marks on the metal surface.

Takano

It’s important to put yourself in the material’s shoes. What state is it in right now? Where are forces being applied? As I place my hand on it, I am picturing the aspects I cannot see.

After a few minutes, Takano lifts the piece off the buff. The metal surface gleams like a mirror. This finish is crucial for examining the material’s structure under a microscope.

This process—cutting a broken part, polishing the cross-section to a mirror finish, and examining its structure under a microscope—is one aspect of materials research. From this, Takano can identify the causes of failure and suggest improvements to the design team. Though the work is not glamorous, these skills are essential for making ever-better cars.

Takano is part of the Mobility Material Engineering Division, a unit within the Advanced R&D and Engineering Company. Home to several hundred engineers and technicians, the division handles all types of materials used in cars, including metals, polymers, catalysts, and battery materials. Within this vast team, Takano is the only member to hold the Takumi title.

The role of materials research is multifaceted. As already described, it includes identifying what causes a part to break and proposing improvements to the design division. It also involves checking new materials to ensure they possess the desired structures; evaluating how materials change when manufacturing methods are modified; and precisely measuring the physical properties used in digital analysis to establish numerical quality standards. All of these fall within the duties of a master materials researcher.

Five steps for revealing what’s hidden

The materials research process can be broadly divided into five steps: cutting, grinding, polishing, etching, and structural assessment using optical microscopes.

When a car part breaks, simply noting the fact that it broke does not lead to improvement. Why did it break? Was it a problem with the material, the design, or the manufacturing process? Uncovering the truth enables engineers to build new parts that won’t fail.

Chairman Akio Toyoda has championed motorsports as a platform for making ever-better cars. Under this approach, Toyota pushes components to their limits on the racetrack, and continuously learns from those that break. If any market defects occur, the causes are investigated. When a new material is developed, its structure must be checked against the design. Materials research skills are essential for all these tasks.

In particular, Takano’s expertise lies in polishing composite materials. This involves creating a mirror-like finish on the cross-sections of parts made by combining different materials, such as aluminum reinforced with carbon fiber, or steel sitting alongside ceramics.

When the materials differ in hardness, however, the harder material will remain raised as the softer one gives way, creating an embossing effect. Just a few microns in height difference (1 micron = 0.001 mm) results in an unfocused image through the microscope.

Working by hand, Takano eliminates such unevenness. Grinding achieves 0.01 mm-precision, while polishing is used for finer, micron-level adjustments.

The first step is cutting, using an abrasive cut-off saw to slice off a section of material for examination. If sparks are produced in the cutting process, the metal’s properties will be altered by the frictional heat generated. To avoid this, water is used to cool the piece while the operator carefully controls the force with which the grinding wheel is pressed to the material.

Takano continued his explanation while his mentee, Senior Expert (SX) Takeshi Yabutani, demonstrated the cutting process. Gripping the handwheel, Yabutani brings the grinding wheel down onto the piece. He turns the wheel clockwise to sink the wheel further into the material, counterclockwise to pull back. By repeating these motions, he makes the cut incrementally, in a technique known as “inching.”

The grinding wheel becomes worn through use, losing its sharpness. What’s more, if you simply keep applying pressure in one direction, powder from the metal sticks to the grinding wheel. Instead, with inching, the wheel is gradually broken down through impact, constantly exposing fresh cutting edges. This action achieves a self-sharpening effect.

Although the machine also has a feature that controls the grinding wheel automatically, Takano does not use it.

Takano

To work efficiently, we focus on examining only the absolute minimum necessary. Even the slightest error in cutting is unacceptable, which is why I do the task by hand rather than relying on machines.

Of course, some of the other staff do make use of these automatic controls. But more than anything Takano trusts the feedback from his own fingertips.

With cutting complete, a specialized machine is used to encase the material in resin, making it easier to grind and polish. Since the pieces being examined are extremely small, in practice, Takano holds the resin during grinding and polishing.

In the grinding process, the piece is sanded with a series of increasingly fine sandpapers—180 grit, 500 grit, then 1000 grit. Here, Takano shares words he has repeatedly impressed upon those working under him.

Takano

I always tell them to approach the material with care. As I mentioned earlier, that means thinking from the material’s perspective. What condition is it in right now? Where is force being applied? How should we grind the piece so that it doesn’t lose its form? As you work, you need to feel with your fingertips and visualize what you cannot see.

Grinding is followed by polishing, the process mentioned at the start of this article. A felt buff is coated with a solution of fine alumina particles in water. These particles start at 0.5 microns and get progressively smaller, to a size of 0.02 microns.

Polished to a mirror finish, the cross-section is then viewed under a microscope. However, its structure is not yet visible—the crystalline structure of metals is not revealed by polishing alone. This is where etching comes in.

Original etching solution reveals a hidden world

Etching is a technique that involves immersing the material in an acidic or alkaline solution, causing a chemical reaction that erodes the surface layer. The crystallites in a metal meet at lines known as “grain boundaries,” which tend to be the areas where impurities gather. These dissolve more readily in acid.

When the grain boundaries are selectively dissolved, they appear as lines under the microscope because the sunken areas cast dark shadows. This allows the metal’s structure to finally come to the fore.

Takano explained the concept using a transmission gear cross-section as an example. Gears undergo heat treatment to harden their surface. In a process known as carburizing and quenching, carbon is absorbed into the metal’s surface, which is then quenched, forming an extremely hard structure called martensite.

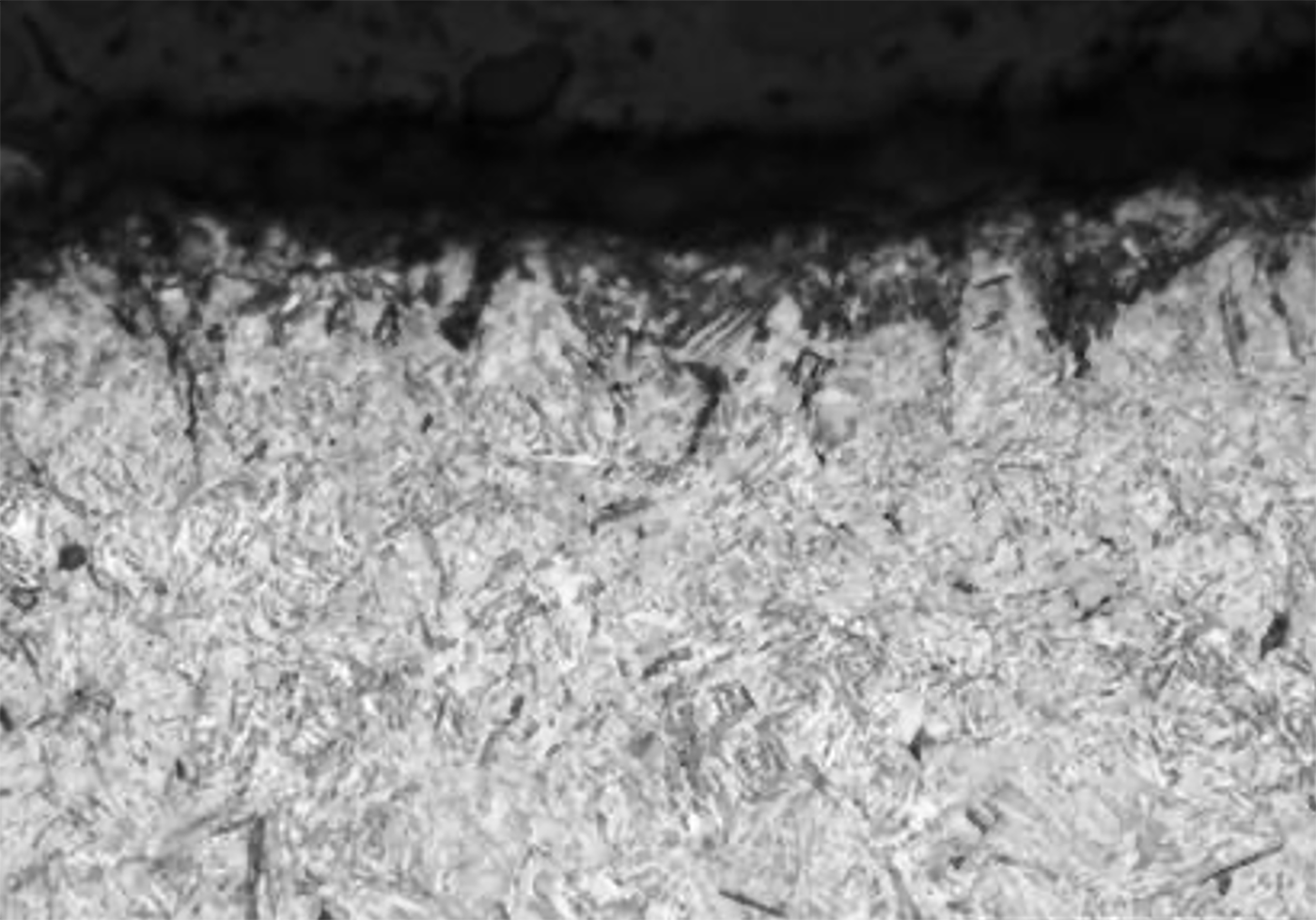

To examine this martensite structure, metals are treated with nital, an etching solution consisting of 3% nitric acid in alcohol. When this solution is applied to a gear cross-section, the martensite structure emerges as a leaf-like pattern.

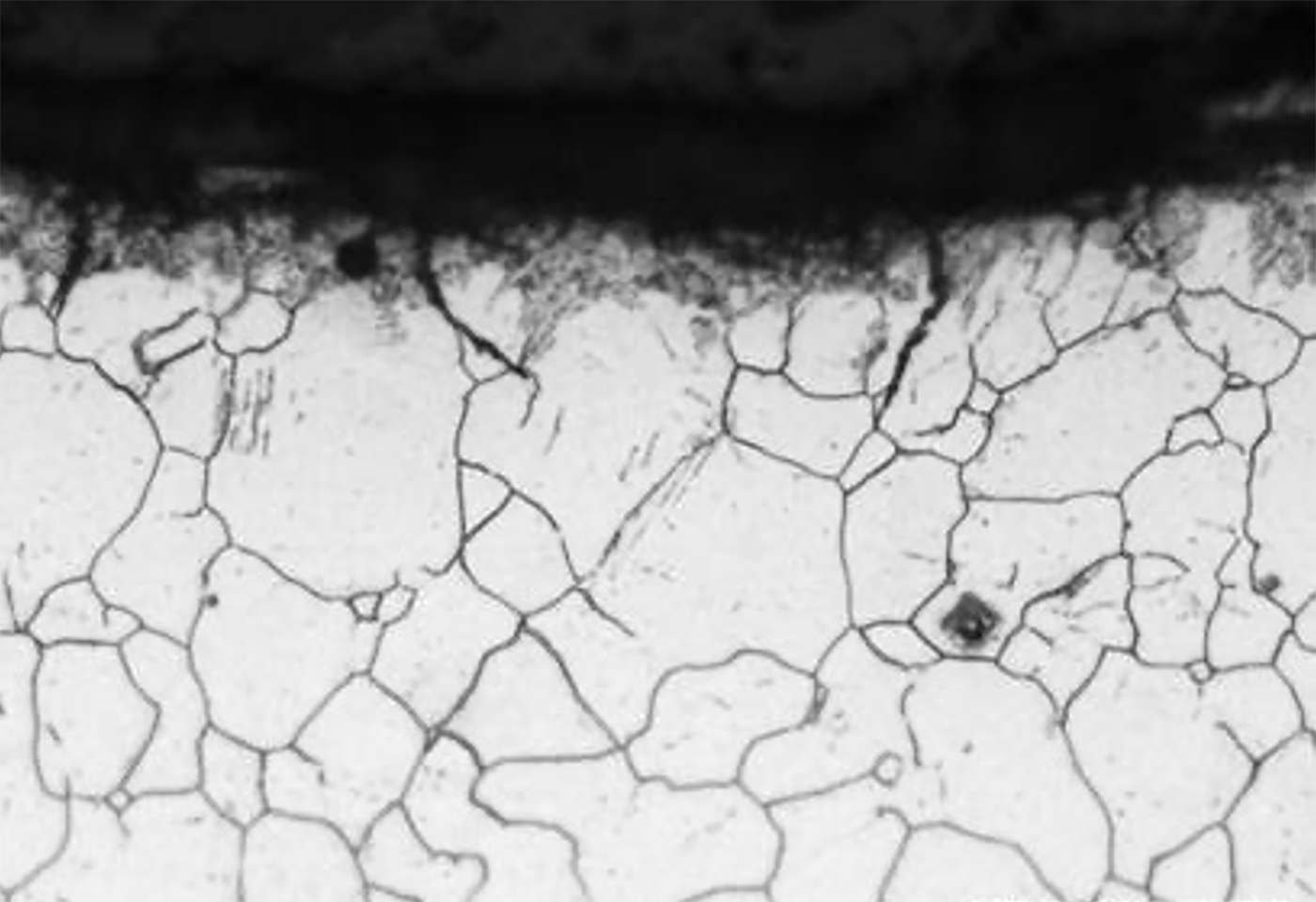

However, this alone is not enough. To evaluate the quality of the martensite structure, it is necessary to measure the size of the crystals from which it formed—that is, the prior austenite grain size. The size of these grains is crucial, with finer grains resulting in a material that is stronger and less likely to break.

Unfortunately, these grain boundaries cannot be clearly seen with standard etching solutions. Takano therefore developed his own etching solution, the result of trialing different acids, concentrations, and mixing ratios.

Takano

These grain boundaries only emerge so distinctly because of our original etching solution.

In the microscope image that Takano showed us, the grain boundaries were revealed in sharp black-and-white contrast. The boundaries between crystals stood out like contour lines on a map, allowing the size of grains to be accurately measured.

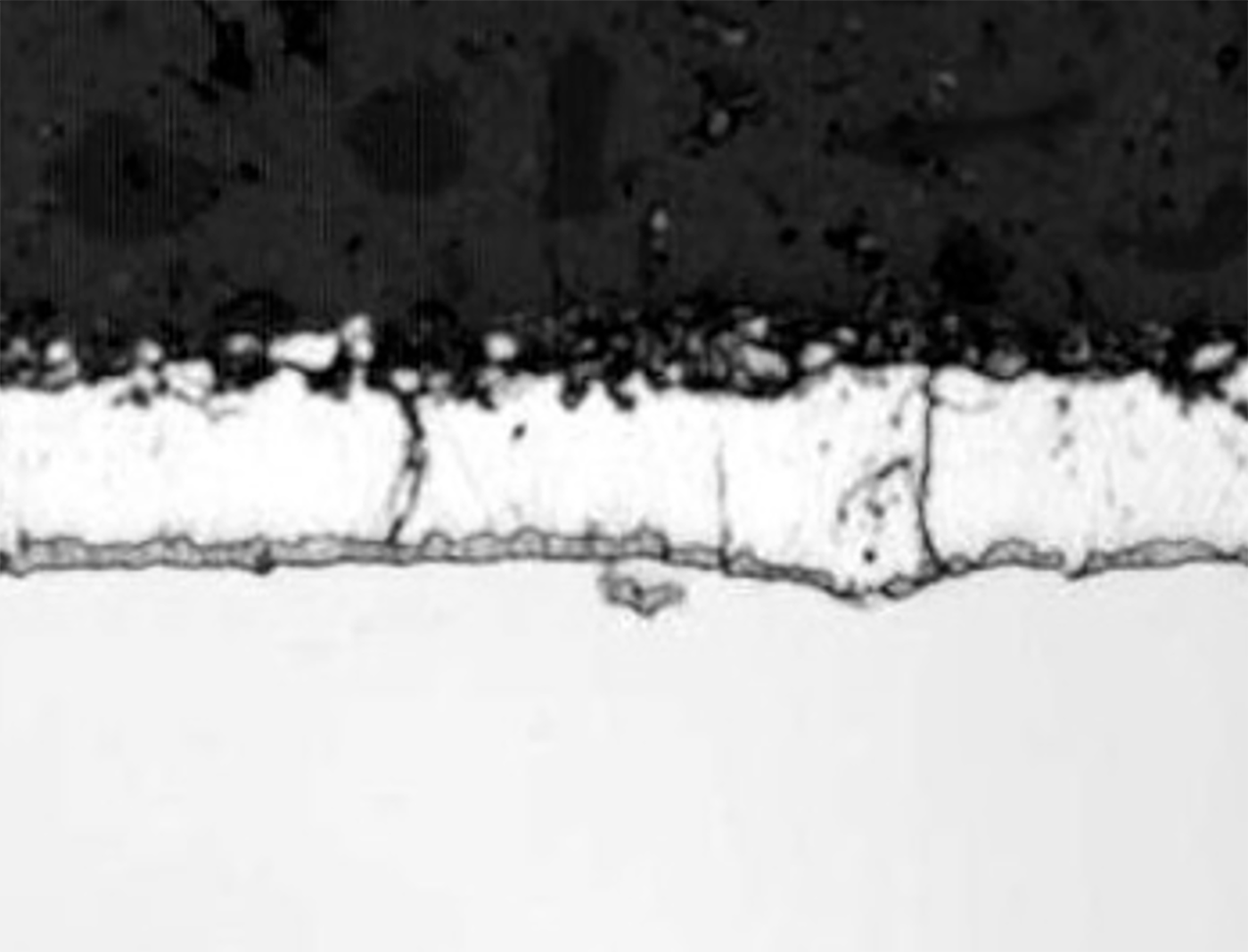

This original etching technique is also being adopted for other materials. One example is galvannealed steel. The steel sheets used in car bodies are zinc-plated to prevent rusting. At Toyota, this does not simply entail coating the sheets with zinc but rather alloying the zinc layer with the iron.

The steel and iron mix together to form an alloy layer known as the Capital Gamma layer. This layer ensures that the zinc plating adheres firmly to the steel sheet. However, if this alloy layer is too thick, its hardness will cause it to crack when the sheet is bent during stamping. It must therefore be kept at an appropriate thickness.

Takano also developed an etching solution that selectively reveals only this layer. When a steel sheet cross-section is immersed in this solution, a distinct alloy layer appears between the zinc and iron. This continued buildup of evaluation techniques underpins Toyota’s product quality.

Defiance in the face of expectation

Mitsuo Takano was born in 1962 in Ibaraki Prefecture. He grew up loving cars, and soon after getting his driver’s license in his senior year of high school, he came to own a second-hand Toyota Celica Liftback, a sports car.

Incidentally, the school Takano attended was not the Toyota Technical Skills Academy, but rather his local Mito Technical High School in Ibaraki Prefecture. At the time, this high school was one of a rare few—reportedly just a handful in the whole country—offering a metalworking program.

Takano

Through this program, I gained the basic skills for working with metals, including forging, casting, machining, and welding.

Making metal, cutting, polishing, examining structures under a microscope—in fact, Takano was learning the fundamentals of materials research. At the time, however, he didn’t grasp the significance. It wasn’t until he joined Toyota that he realized it would become his life’s work.

Takano came to Toyota Motor Corporation in 1981 and was assigned to the Testing Section in Engineering Division No.5. Back then, it was a small unit with fewer than 100 members.

As the first graduate from the Mito Technical High School’s metalworking program to join the Material Engineering Division, Takano faced high expectations from senior colleagues.

Takano

Since I had gone through Mito Technical High School’s metalworking program, many of the older members just assumed that I would be able to do certain things.

Expectations turned into pressure, which bred defiance.

Takano

Being told “You should be able to do this,” I became determined to prove myself. With time, I found myself mastering these skills.

Takano began devoting his days to honing his skills. In the early 1990s, he was involved in developing belts for CVT (Continuously Variable Transmission), at a time when Toyota was trying to develop its own version of the technology.

Working in rotation with engineers, Takano immersed himself in development experiments that involved applying unique heat treatments to metal belts, called hoops, using ammonia gas.

Takano

In those days, I really didn’t even have time to sleep. The more experiments we conducted, the more they revealed. We kept moving forward through trial and error, always trying the next thing. Action led to results. That made it very exciting.

In 1997, Takano took on a new challenge: developing lithium-ion batteries. As an expert in metals, he was dispatched to the battery development team.

Takano

I figured there was no point doing things by halves, so I started learning about lithium-ion batteries from square one.

Development began with making compact, button-cell-sized batteries by hand. The fruit of these efforts, known as “Version 0,” was adopted as an auxiliary battery for the idling stop system in the Vitz (now the Yaris).

Through this experience, Takano greatly broadened his skill set. He gained the knowledge necessary to handle not only metals but all kinds of materials, including plastics, ceramics, and catalysts.

In the second part, we trace Takano’s path to being recognized as a Takumi, his genba efforts assisting design as the go-to analysis expert, and the work of passing on his skills to the next generation.