This series explores the project to restore a first-generation Crown, a car that embodies Toyota's origins. Part 4 covers the body restoration and special coating process designed to keep this cherished car on the road for decades to come.

Far rustier than expected

In a corner of the Motomachi Plant being used for painting work, the body of the disassembled first-generation Crown finally stood ready for restoration to begin. Led by final line assistant manager Minato Ishibashi (Body Section No.1, Body Manufacturing Div., Tsutsumi Plant), the team entrusted with this task brought together nine experts from across the company, including production genba staff from the Tahara, Takaoka, Tsutsumi, and Motomachi Plants, and welding specialists who can normally be found building prototypes at the Technical Development & Prototype Div.

Team leader Ishibashi recalls the condition of the body at that time.

Ishibashi

The chassis was very solid, and with the paint on the body, it also seemed to be in good condition.

The way things looked initially, we felt we could wrap up the body restoration work within a month. However, when we removed the interior and core components, we realized it would not be so simple.

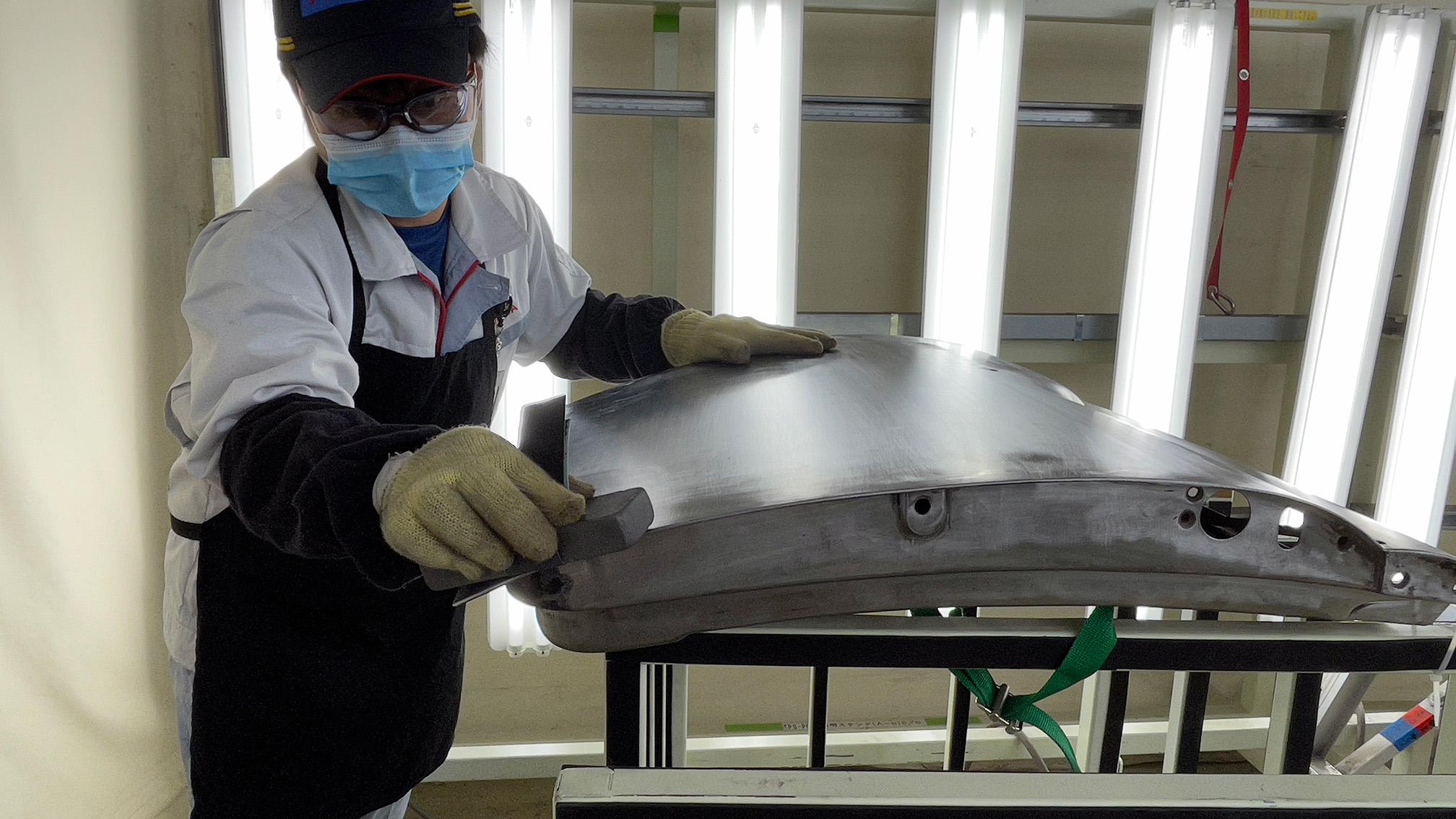

Team members began by using paint remover to completely strip the paint from the body, returning the body panels back to silver-colored steel sheets. In doing so, they uncovered countless sections of bright red rust and minor dents that had lain concealed under the paint.

More than six decades of rust and dents had taken a severe toll. In particular, the corrosion on the underbody, which is not visible from outside, and areas where rainwater inevitably pools, such as the bottom of doors and wheelhouses, turned out far worse than expected.

Remaking body panels from molds

These circumstances turned the body restoration into a far more colossal and difficult task than even the team of crack technicians had imagined. Another reason was the fact that, as befitting a car manufacturer, they were aiming for a flawless restoration that would surpass the quality of the original down to the innermost details.

Right from the initial rust removal, the work was extremely arduous. It involved meticulously removing the rust by hand using a file and paste. Any speck of rust left on the surface would show up when the body was painted, creating an uneven area that would ruin the beautiful finish and allow corrosion to set in again. This meant there could be no compromises.

One of the team members, SX Takaaki Sato from the Lexus Body Section at the Tahara Plant’s Body Manufacturing Div., describes the challenge.

Sato

Unlike today’s cars, in the first-generation Crown, the joints between parts were not sealed. This means that, given the car’s age, rusting was inevitable.

And yet, seeing the extent of corrosion brought home just how terrible rust is. We also found makeshift repairs where dents in the body had been patched up with putty, which couldn’t be left as they were.

After several weeks of removing rust by hand, the team was finally ready to move on to panel beating. This step entailed using hammers and other tools to manually knock out any dents and return the metal to its original form.

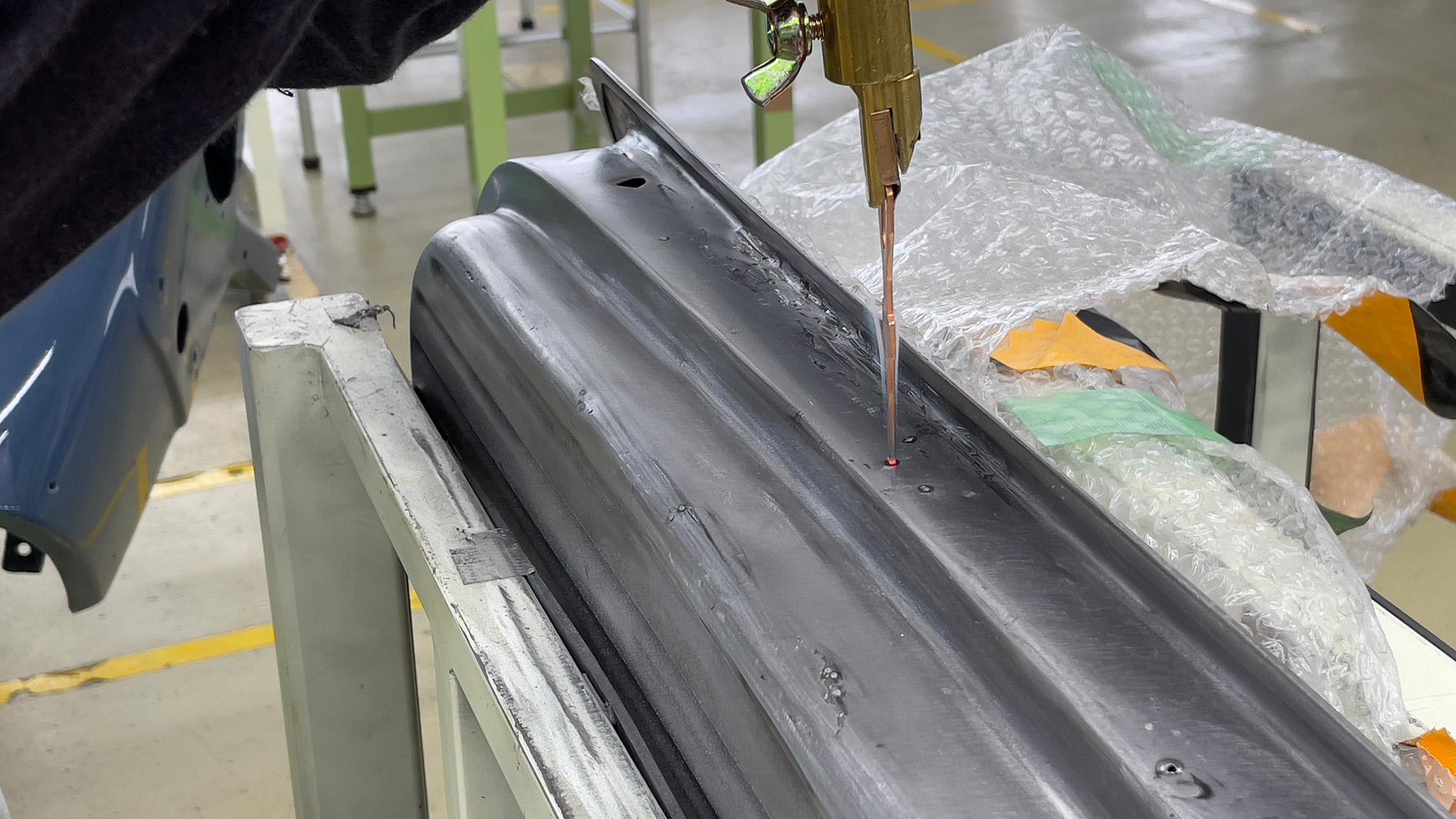

In sections that had been patched up with putty, the putty must first be removed before the panels are beaten. Smaller dents are repaired one by one using a method called “stud welding,” in which a copper stud is temporarily welded to the surface of the dented metal, where it can then be pulled on to draw out the dent.

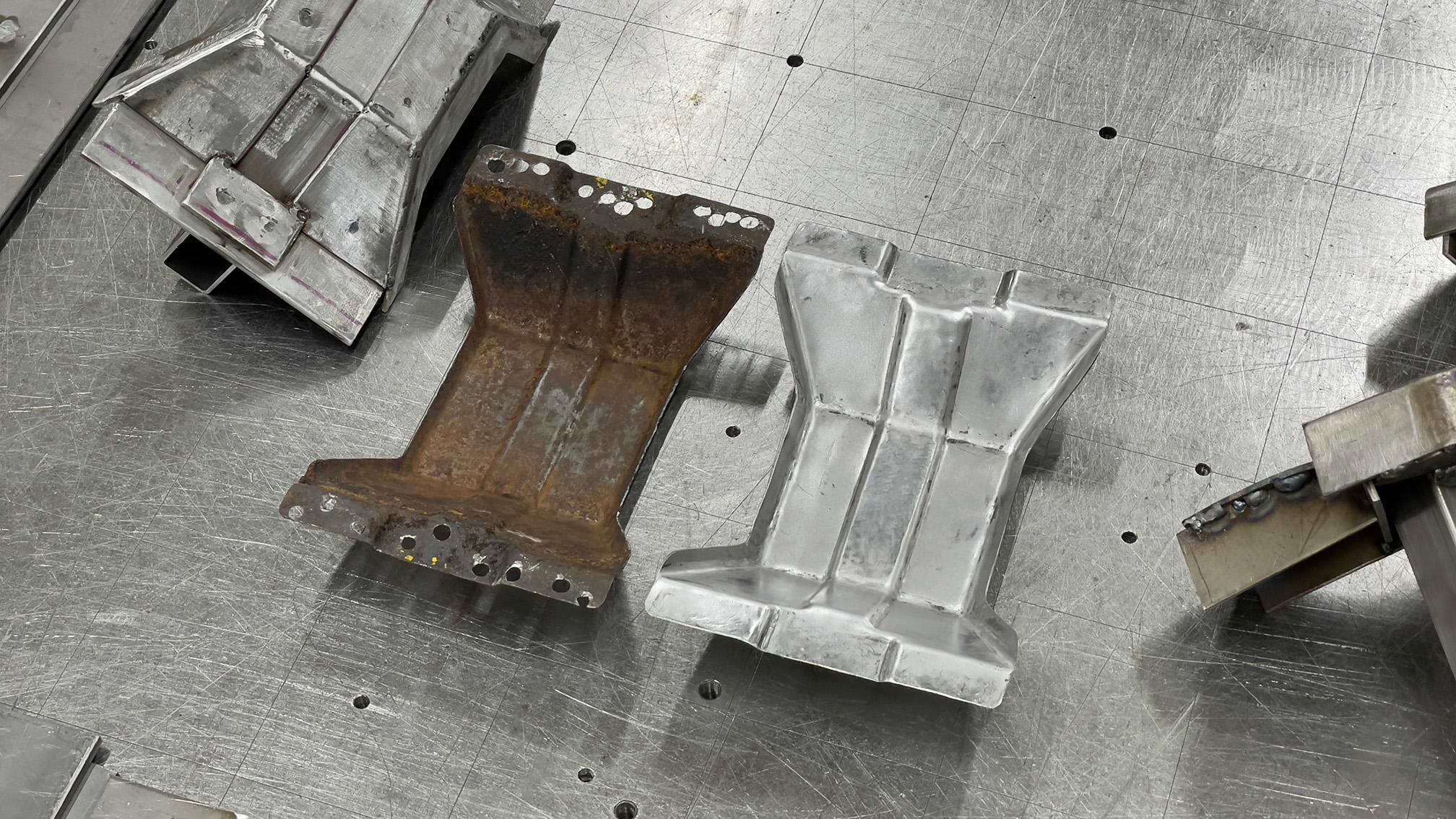

Unfortunately, not much can be done about areas where a steel sheet has been thinned by rust removal or corroded to the point of having holes. The first-generation Crown’s body was assembled by welding together many panels made of steel sheets.

Where the damage is minimal, the area can be repaired by welding on another steel sheet. If a panel is severely damaged, however, the only option is to remake the entire piece from scratch with sheet metal working. This means making a mold of the panel, which is then used to hammer the steel sheet into the desired shape.

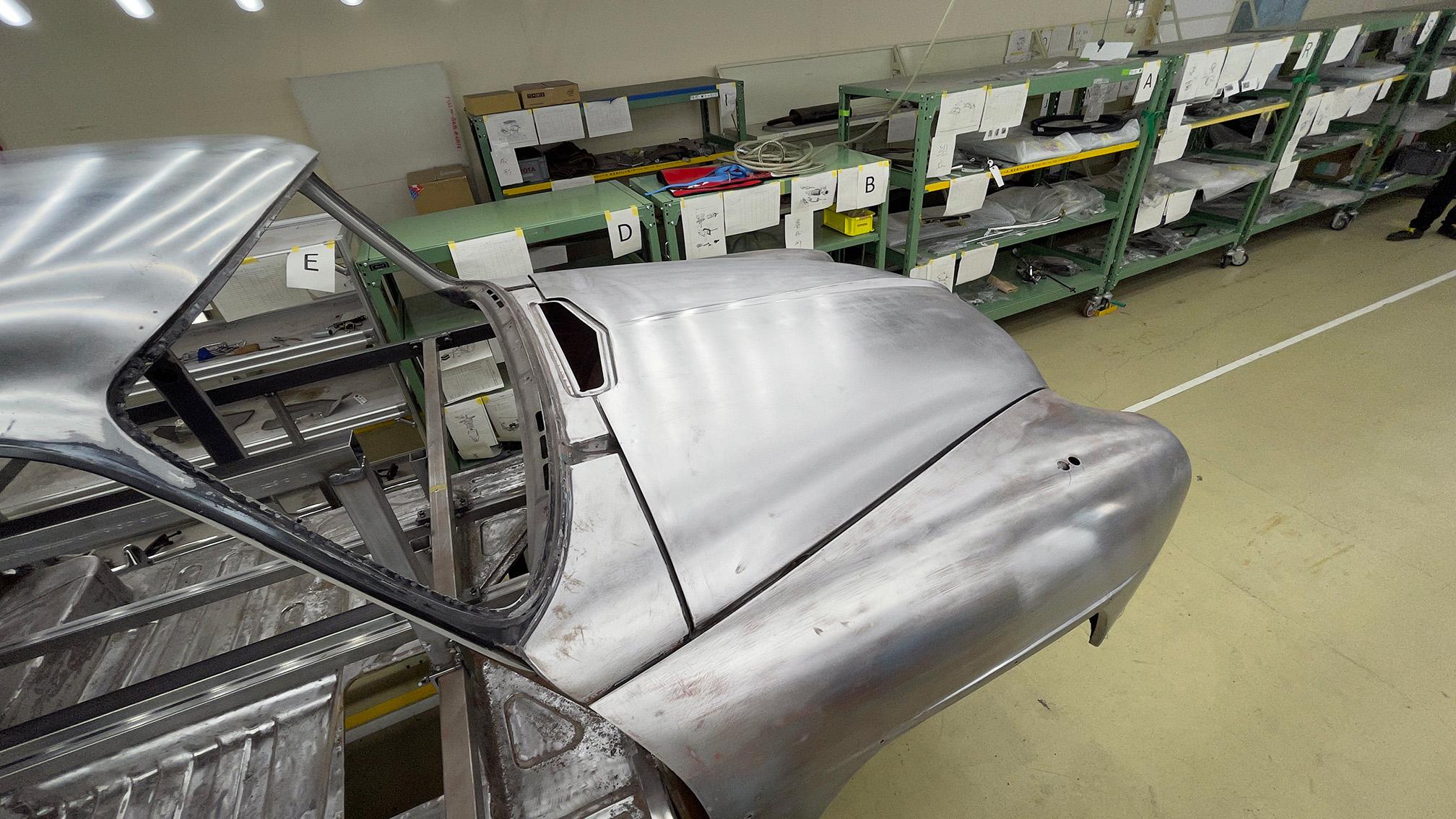

Despite the constant challenges, the body team’s nine experts pressed on tirelessly with the panel beating, welding, and panel fabrication. As it happens, Ishibashi is a master welder who has guided plant start-ups in Japan and around the world.

Ishibashi

I’ve been involved in production site work for many years, but this restoration project was full of new experiences. For instance, in my whole career, I had never made body panels from molds. We were able to complete the task through the joint effort of our skilled production technicians and Prototype Division members.

As the work progressed, we found more areas that we wanted to improve. Time and again, I ended up asking our members’ various departments to let them stay on longer.

At thirty-six, Takahito Ninomiya from the Takaoka Plant was one of the team’s younger members. He too recalls the body restoration work as a daily process of trial and error.

Ninomiya

The basic tasks were the same as my regular work, yet somehow, we struggled. Even at its thinnest, the first-generation Crown’s body measures at least 1mm, much thicker than today’s cars. Trying to hammer the body back into its original shape doesn’t work out as you imagine. Every step is a challenge. You just have to get in there and try.

The more difficult the work, the more determined the team became. Going through the process also gave them a greater appreciation for the incredible skill of the people who had built the car 65 years earlier.

The more difficult the work, the more determined the team became. Going through the process also gave them a greater appreciation for the incredible skill of the people who had built the car 65 years earlier.

Ishibashi

Take for example the exquisitely rounded fender, which forms one of the highlights of the streamlined body. This section is composed of three panels welded together. To pull off such advanced welding without the equipment we have today, the craftsmen of the day must have been incredibly skilled.

Alongside conventional sheet metal welding techniques, Toyota used “incremental forming,” a method rarely seen on car body mass-production lines, to fabricate the Crown’s panels. The restoration team’s efforts to introduce such new methods will be featured in future articles in this series.

After several months that presented an “all-round challenge” even for Toyota’s skilled veterans, the body restoration work was completed at the end of October 2022. With that, the team moved on to the next step: painting.