Even in the face of technological hurdles, what drove Toyota's development team working on humanoid robots of the Tokyo 2020 mascot characters, Miraitowa and Someity, was a desire to bring smiles to children's faces.

As a worldwide partner, Toyota supported the Olympic and Paralympic Games Tokyo 2020 not only with vehicles, but also with a variety of robots. This three-part report highlights the tireless efforts of project members behind the scenes of the Games. Part 3 showcases the mascot robot project team.

Putting children’s smiles first – Shifting away from technical appeal

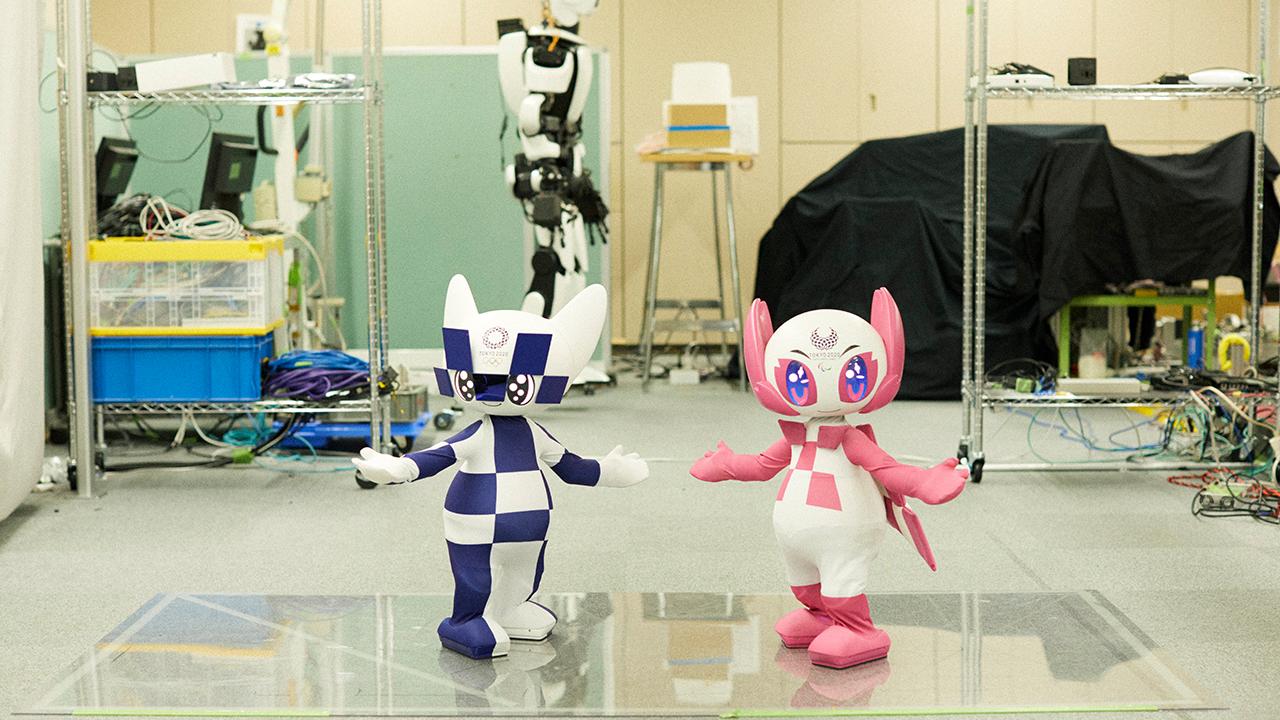

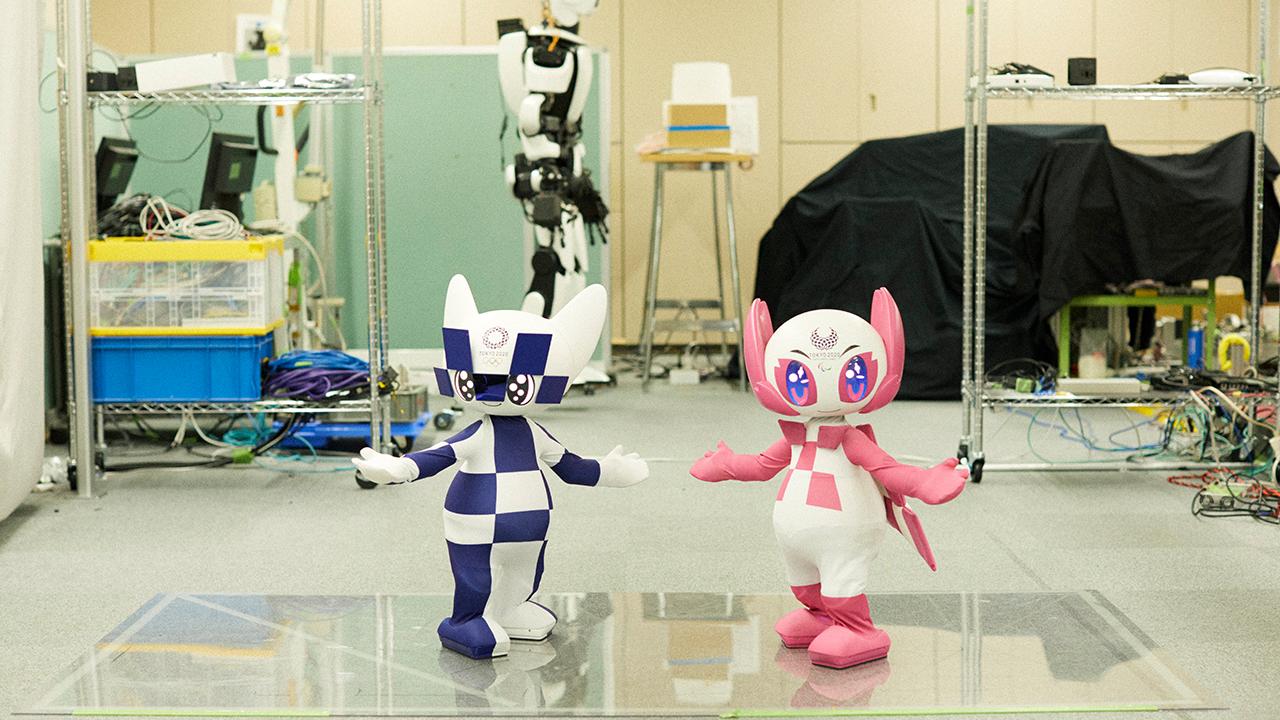

The mascot robots were robotized versions of the official Tokyo 2020 mascot characters, Miraitowa and Someity.

In 2018, the Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games launched the Tokyo 2020 Robot Project to promote the adoption of robots in society. As part of this initiative, development began on mascot robots that could read and seamlessly respond to human expressions and gestures by using force feedback (transmission of force between robots) and AI recognition.

By the beginning of 2020, development was approaching the stage of improving the accuracy of AI communication with people. Then, as the sudden spread of COVID-19 forced the Games to be postponed, plans for using mascot robots also had to be reconsidered.

Prior to postponement, the robots had been assigned two main roles during the Games. First, they were to be displayed at various locations, including showrooms and airports welcoming athletes and overseas visitors.

Second, they were to be part of the Front-Row Seats for Future Stars Project jointly organized by the Tokyo 2020 Organising Committee and the Tokyo Metropolitan Government. This initiative catered for students with special needs who cannot easily attend event venues, offering the experience of seeing the Games in person by using mascot robots to remotely control T-HR3 humanoid robots at competition sites.

With the Games postponed, however, these plans were greatly revised.

For the Olympics, the Front-Row Seats for Future Stars Project would feature only the mascot robots, remotely controlled via tablet devices.

For the Paralympics, the new role of the robots would be to welcome and see off children visiting Games venues as part of a school spectator program.

Tomohiro Nomi (project leader)

With the pandemic severing in-person contact, we wanted to create ways for people to connect and interact safely, regardless of distance, through the use of robots.

Before the Games were postponed, we felt that the purpose of these mascot robots was to show off our force-feedback technology, so mobility and expressiveness weren’t part of the development brief. The robots were fixed at the waist, so they couldn’t stand or walk. Even though the force-feedback technology was quite advanced, they probably looked like toy robots that could only flap their arms and legs.

We reconsidered the exteriors and functions of the robots so as to strike a chord with children and set about creating an authentic feel with the following three goals: 1) natural movement using the entire body, 2) an appearance that didn’t feel robotic, and 3) natural interaction with their surroundings.

At the same time, regardless of how much improvement we made, when it came to AI-driven communication, we could never guarantee a 100-percent success rate. How would children feel when they saw them? Our error rate may only be 1 percent, but if a child’s only experience with our robots is with error, that’s 100 percent for them.

Thinking about how they would feel, we came to the conclusion that we could not apply technology without a perfect success rate. That’s why, halfway through the project, we abandoned the use of AI technology and started again basically from scratch, developing a remote-controlled robot.

At the time, I think many of our team members wanted to showcase Toyota’s AI technology. In the end, we made the tough decision, with our top priority being to make children happy.

Over the next year or so, rapid developments took place.

Stocky bodies defy robotics theory

So, let’s see the differences between the old and new robot designs models before and after the postponement of the Games.

The R-Frontier Division’s Hiroyuki Kondo, who was tasked with hardware design for the project, recalls when development was restarted.

Hiroyuki Kondo (hardware designer)

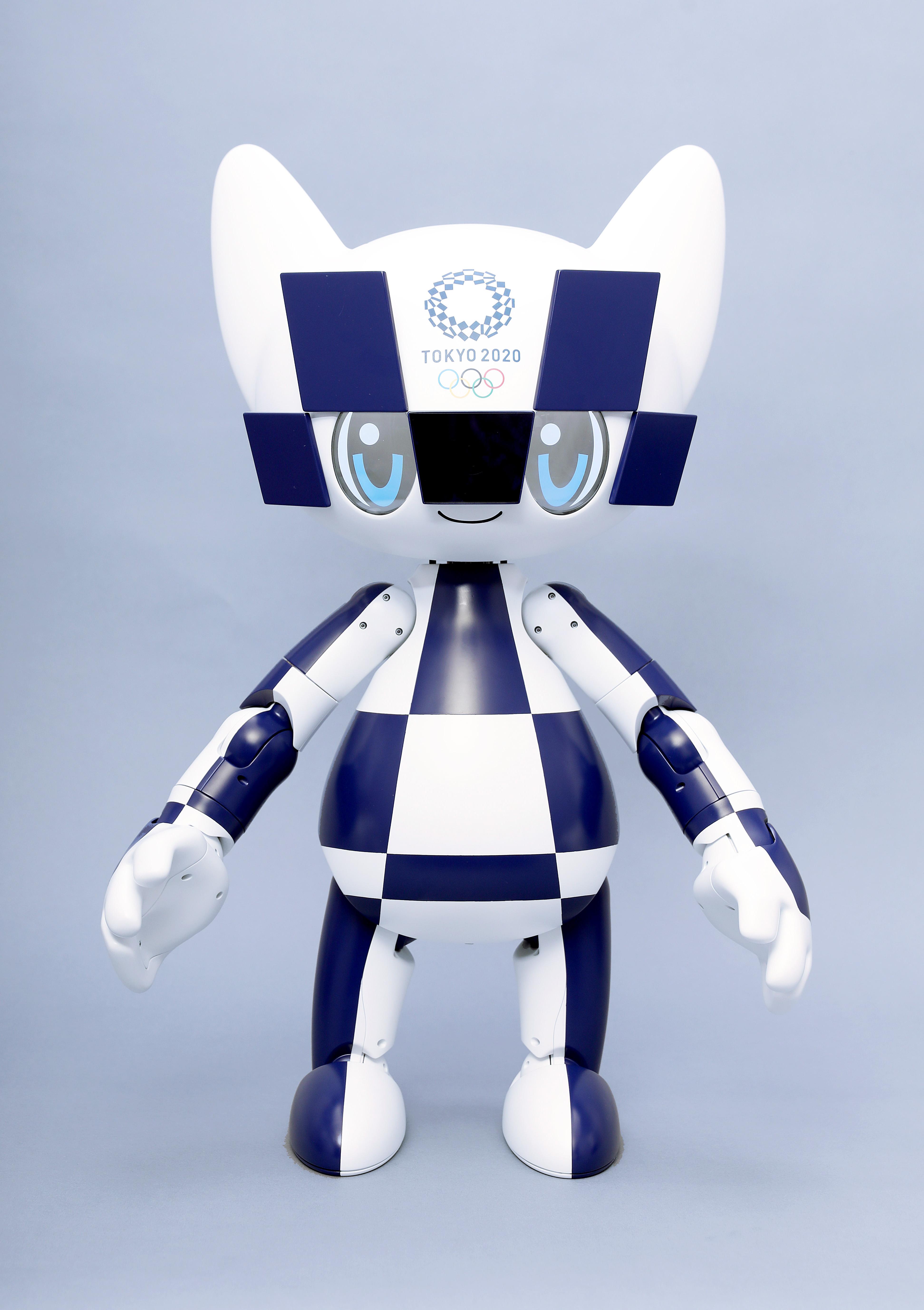

The Miraitowa and Someity character designs were a vast departure from the forms of standard bipedal robot theories.

Compared to humanoid robots based on human proportions, such as the T-HR3 already in development by Toyota, they had extremely large heads and short limbs. While such stocky body shapes may add to the characters’ charm, a head heavy in relation to the body would sway with every motion and make the robot’s movements unstable. Some experts in the field of robotics went so far as to say that a bipedal robot could not be built with this body shape.

And most importantly, these bodies were too small to fit all the necessary parts. We had somehow managed to cram everything into the small frame of an earlier model, but now we had to add axes of rotation and increase power so that the robot could stand on its own. That made for an extremely difficult challenge.

To overcome these problems, we began by developing a compact motor that could fit inside those small bodies.

At some 65cm tall, the mascot robots reach around the height of a child's waist and are rather stocky in stature. Figuring out how to arrange parts in such a small body was a crucial problem, which marked the start of a project that had to defy established theories of robot development.

From “building robots” to “making realistic mascots”

Seeking to improve the robots’ movement, some team members felt that the fixed waist led to stilted motions that gave the impression of flapping limbs. This issue was solved by adding 8 new joints to the 20 already in place. To ensure both mobility and expressiveness, the team also worked rapidly to improve power output and posture control.

While seeking to create diverse gestures and expressions, they also studied the irregular, random movements of living things.

Tomohisa Moridaira (engineering leader)

We wanted children to come away feeling as though they had met the real Miraitowa and Someity, so we shifted our mindset from “building robots” to “making realistic mascots.”

One example is eye movement. In the case of a person, the eyes turn towards an object first, then the head and torso follow. To reproduce such lifelike movements, in addition to motion sensors on the limbs and body we needed to recognize the operator’s eye movements via camera and incorporate them into the remote-control system.

On the other hand, if the mascot robot were to raise its arm in the same way a person did, that arm would hit the robot’s large head. We’ve devised ways for the software to coordinate movements in real-time to absorb these physical differences between operator and robot, ensuring the robot’s body shape did not interfere with its movements and still retaining the character of individual motions.

Repeated testing enabled us to identify the unique movements of the mascot’s stocky body and boost accuracy through both robotic and control technologies.

By switching the basic system of operation to remote control, the robots achieved a 100 percent success rate for communication, and became capable of producing realistic movements similar to a living creature.

At this point, the team had reached the “authenticity” goal, however, the trial-and-error process of bringing smiles to children’s faces still had some way to go.

Tomohiro Nomi (project leader)

When the decision was made to postpone the Games, we hoped that the mascot robots might help to dispel the headwinds faced by the Olympics and Paralympics, creating an atmosphere in which the world could look forward to a brighter future.

Ahead of the Games, we wanted to drum up as much support as possible by engaging people around Japan. We assumed that children who met our mascot robots would get excited about the Games. We figured that if their kids were excited, parents would at least not feel negativity around the event being held.

To that end, we set a goal of having our robots appear on Kohaku Uta Gassen (an annual New Year’s Eve television special) at the end of 2020, where they would dance to Foorin’s “Paprika” alongside elementary school students from around Japan.

This mission also had the goal to make lifelike mascots that would bring a sparkle to children’s eyes. Seeking to create movements that differed from the uniform motions of ordinary robots, the software developers themselves mastered the dance routine.

By recording and programming the data obtained in this way, they sought to produce movements so natural that it felt as though a small person was inside each robot.

Kazuya Yamamoto (software developer)

After more than 200 tests and modifications, the mascots came to move more smoothly. To teach dance moves to our robots, I learned the steps myself and performed them over and over. Before development began, I never dreamed that I would be learning to dance.

With only my data, however, Miraitowa and Someity would dance in unison with identical moves, which would look robotic. I wanted one of them to use data from someone else.

We decided to get a former cheerleader from Alvark Tokyo (Toyota’s professional basketball team) to dance for us and fed that data into Someity. Some of the movements didn’t translate well in the stocky mascot robot, whose limb and head proportions differ from a person, so instead of copying the human dance steps exactly we made adjustments to eliminate clunky motions.

By recording separate dance data for Miraitowa and Someity, each robot had its own moves that seemed to provide them with unique personalities. As robot movements were refined, the team also revised the exterior designs to make the mascots even more lifelike.

“On the earlier model, the body joints were exposed, so you couldn’t shake off the impression that it was a mechanical robot,” says hardware designer Kondo.

To fix this perception, the team updated the robots’ attire, covering their entire bodies with a single piece of material as elastic as animal skin.

Beneath the material, the joints were wrapped in flexible resin covers that conformed to their movements to avoid looking awkward, even during dynamic dance moves. The stiffness of material was adjusted to suit the function of each body part, with some areas sporting firm covers to protect internal components where necessary.

For this, engineers borrowed the 3D technology used in concept cars. The exterior design also drew on garment-making techniques, from positioning seams for a neat appearance to choosing material colors and thicknesses that would ensure the body did not show through.

The robots’ emotional range was also enriched by expanding eye expressions to 13 compared to the 8 from the earlier model.

Turning dreams into reality

Although the robots ultimately missed out on appearing in the Kohaku Uta Gassen, in April 2021 they performed with Foorin on NHK E’s Minna no Uta program.

By the time of the Games, children were running up to the mascots like old friends, calling out, “Hey, it’s Miraitowa.” According to project leader Nomi, the children seemed to believe they were meeting the real Miraitowa and Someity, not their robotic lookalikes.

Similarly, during visits to special needs care facilities as part of the Front-Row Seats for Future Stars Project, the children were delighted and surprised that the mascots really were robots without someone inside. Some of the parents also commented warmly that they rarely saw their children being so expressive with their eyes and bodies.

“From the outset, this project was driven by the children’s dreams of experiencing the Games firsthand, and our team members’ dream of providing special experiences that made those children feel as though they were really there, even though they couldn’t attend in person,” recalls Nomi.

“And we were able to turn their dreams into reality. Witnessing the joy that radiated outward from the mascot robots made me realize that this was more important than showing off technology, and I’m sure it changed the mindset of other team members as well.”

He went on to describe new insights gained through Tokyo 2020 that will benefit future robot development.

Tomohiro Nomi (project leader)

I imagined that communicating without words would somehow be inconvenient, but in fact, the opposite was true. Be it winks or heart-shaped eyes, people were keen to perceive changes in the expressions and gestures of Miraitowa and Someity’s, envisioning the robots’ emotions and reacting accordingly.

Time and again I witnessed people engaging with the mascots in this way, compensating for any communication elements that may be lacking in their interaction.

Excluding the medium of speech led to more communication, as people sought to better understand the robots’ feelings. We were able to glimpse the ideal relationship where people and robots mutually engage with each other. I doubt this intimacy could have been forged if the robots had been able to speak.

The future of robots is not just about technical innovation; another crucial aspect is figuring out how they might connect with human emotions in the same way as friends or family.

In highlighting this fact, the project proved a good experience that offered hints for future robot development. After Tokyo 2020 safely drew to a close, the fruits of those efforts led to the next mascot robot.

A baton passed to the future

That next step was developing a robot Bear Atsushi, the official mascot character who serves as the host of NHK’s new program, Reformer’s Cane (Educational TV).

Tomohiro Nomi (project leader)

Until now, such mascots have been operated by puppeteers, but the dwindling pool of puppeteers due to aging has presented a challenge for the producers of children’s educational programs. A person wearing a costume, on the other hand, will inevitably be bigger in stature, which some children may find frightening, ending in tears.

Our new mascot robot is around 70 cm tall and capable of communicating with gestures like a living being. After supporting our efforts with “Paprika,” NHK approached us with the idea of using this technology to create a new kind of program.

Finding new partners helps us to understand the challenges faced in various fields, which is valuable in making Toyota’s technologies ever more useful in people’s daily lives. That is another lesson we learned by growing our network through Tokyo 2020.

Behind the scenes, Bear Atsushi is controlled by famous Japanese TV personality Atsushi Tamura. For the program, the robot has been updated to recognize the operator’s facial expressions, which it mimics by moving its eyebrows and mouth.

The mascot also dances to the program’s theme song. Whereas before the Olympics programming a dance routine took months of coordination, that timeframe is now down to around one week.

Even as the robots gradually become more capable, development times are getting shorter. “We’ll continue pushing ourselves to make this technology fit for a wide range of uses,” says Nomi. The journey towards creating new lifestyles continues.

Toyota is the Official Worldwide Sponsor of the Olympic and Paralympic Games