As a business leader, Akio Toyoda has approached countless decisions with a mindset rooted in the Toyota Production System. We share the lecture he delivered to a 200-strong audience of fellow corporate managers.

Fighting to break down Toyota’s walls

From the Operations Management Development Division, in 1992, I moved into domestic sales and became a regional representative for dealerships. I couldn’t believe what I saw there.

While the production genba used expertise and ingenuity to shorten lead times, cars that spent mere hours in the assembly plant were languishing for weeks in dealers’ yards.

It seemed like Toyota’s Just-in-Time approach only applied within production plants; a thought that made me desperate to do something.

Wasn’t Just-in-Time about connecting Toyota with dealers and customers? With this in mind, I established a team to improve operations within the domestic sales division.

Unfortunately, this was an unwelcome presence for both the sales division and the dealerships.

Others viewed us coldly, saying, “TPS, Just-in-Time, call it what you like—making products and selling products are two different things.”

Ten years had passed since the merger of Toyota Motor and Toyota Motor Sales, yet thick walls still divided production and sales.

Chairman (Masahiro) Morikawa of Netz Toyota Tochigi, who worked with us on improving the sales genba, shared his recollections from that time.

Please watch this video.

The experience of improving dealerships made me realize something: TPS is not just for the production floor. It can be applied to all tasks, workplaces, and genba. And it can break down the walls that impede change.

Administrative and engineering elites in the head office always put up these walls.

Going to the genba and engaging people to pursue improvement is certain to break down the walls erected by boardroom elites.

This conviction has helped me break down many walls.

2. Used car kaizen and GAZOOIn the process of improving dealership operations, we turned to the potential of the used car business.

We set out to develop an image system for used cars, in which digital photos of trade-ins were made available on terminals across all sales branches for immediate negotiation to shorten lead times for the resale of trade-in vehicles.

Although the system was revolutionary for its day, we met fierce opposition inside Toyota, with people arguing that pictures would never sell cars.

Since our system was not allowed to bear the Toyota brand, we named it GAZOO, from the Japanese word for “image.” This is where GAZOO originated.

From that point on, for me, GAZOO has become a beacon of change.

3. Nürburgring, Naruse, and making ever-better carsWhat started out as a signal of change toward making ever-better cars has today grown into GAZOO Racing, or GR, a global sports car brand.

It all began 23 years ago when I met legendary test driver Hiromu Naruse. This is what he said the moment he saw me:

“Test drivers put their lives on the line in these cars. We don’t want to be told what to do by people like you, who know nothing about driving a car. But if you are interested, I will teach you.”

Thus began my driving training.

Naruse followed an unwavering principle: roads build people, and people build cars. This makes motorsport an ideal foundation for making ever-better cars, by honing both vehicles and people.

Driven by this conviction, Naruse encouraged me to compete in my first Nürburgring 24-hour endurance race. I did so in June 2007.

Since I was vice president at the time, GAZOO was widely slammed as “Akio’s hobby,” something the Toyota heir was doing for his own amusement.

Naturally, we received absolutely no backing from the head office and could not use the Toyota name.

Instead, I decided to go by “Morizo” and named the team “GAZOO.”

And, of course, we had no money, so we fielded two Altezzas purchased second-hand.

Please watch this video of the race.

Although both cars miraculously managed to finish the 24 Hours of Nürburgring, it was also a very frustrating experience.

Other manufacturers ran sports cars they were developing for future release. Toyota, however, didn’t have a current sports car that could be honed at Nürburgring.

Every rival car that flew past seemed to be saying, “Toyota could never make a machine like this.”

Having constantly been told that I wasn’t up to the task, the frustration and defiance sparked by these words became my driving force for making ever-better cars.

Taking over a company in crisis

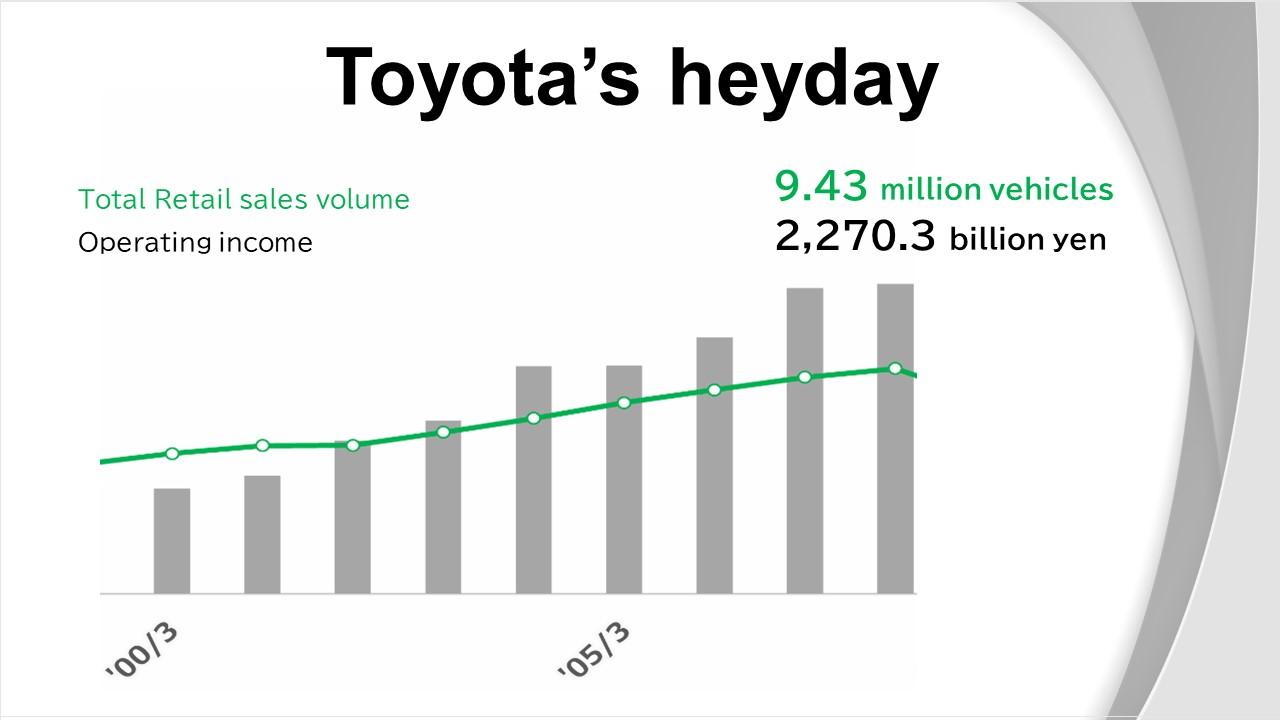

Around the time I was taking on Nürburgring, Toyota set new global sales records every year, led by growth in the U.S.

As we overtook GM to become the world’s largest automaker by volume, many articles and other publications came out praising Toyota. We were truly enjoying our heyday.

Everyone thought this momentum would last forever. Then came the Global Financial Crisis.

The crisis would push GM to bankruptcy. Similarly, Toyota instantly lost over 2 trillion yen in profits, falling into the red for the first time in company history, just as I became president.

I had to prove myself, as people both inside and outside the company waited for me to slip up and quit, thinking, “There’s no way this third-generation princeling can overcome such a crisis.”

I feel I was the president no one wanted. Despite that, I worked without rest, frantically scrambling around the genba in an effort to somehow rebuild the company.

I continued to tell my Toyota colleagues only one thing: “Let’s make ever-better cars.”

And I continued to put my own life on the line behind the wheel as a test driver.

Showing people that I would never stop working and that I would risk my own life to develop cars—I could think of no other way to turn Toyota around.

2. The public hearingsAmid this recovery, Toyota was hit by a crisis that posed an even greater threat to the company’s survival: a global-scale recall problem.

With trust in Toyota crumbling, I traveled to the U.S. public hearings in my role as the rearguard.

Looking back, it was almost like throwing myself under the bus. I felt forsaken by both my company and my country.

Again, I felt like I was being told that I wasn’t up to the task.

Embattled from all sides, I realized the only thing I could do was convey Toyota’s sincerity.

I would honestly accept criticisms that our response was slow or inadequate and apologize. At the same time, I would fight tenaciously against any baseless accusations about lying, concealing, or deceiving.

I would show the true Toyota, not just to those in Congress but to the many people beyond.

My actions would help to protect Toyota’s partners and demonstrate to the next president what it means to take responsibility.

In resolving to do this, I still vividly remember the joy and delight of feeling that, for the first time since joining the company, I might be able to serve Toyota.

When faced with the recall problem, I made a promise to the people of the world: I would not run away, lie, or distort the truth.

I was able to make this pledge because of my colleagues in the genba.

At Toyota’s head office, our engineers worked day and night, repeating driving tests and exhaustively pursuing the truth.

There is nothing more powerful than the truth. I’m convinced that this TPS mentality, alive in our genba, saved both Toyota and me.

And, after putting myself on the line to defend my colleagues, it was, in fact, I who had been protected by them. When I realized this, tears welled up in my eyes.

At a later general meeting, a shareholder commented that “a president should not show his tears,” but there was nothing I could have done to stop them flowing at that moment.