There were already signals of the onset of a hot, tropical summer in Singapore. It was here at the mouth of the Singapore River, which twists its way through the urban landscape, where Singapore's most-iconic Merlion statue graces the waterfront, while the popular Marina Bay Sands resort is situated nearby, the combination of which created picture postcard views of this Asian city-state. While many people travel to Singapore for business or vacation, Takeshi Kawamoto ventured here to hone his "warrior"skills.

※The article has been published in Toyota Global Newsroom on July 26, 2019.

Swimmer Takeshi Kawamoto, 24, works in Toyota Motor Corporation’s e-TOYOTA Division.

There were already signals of the onset of a hot, tropical summer in Singapore. It was here at the mouth of the Singapore River, which twists its way through the urban landscape, where Singapore’s most-iconic Merlion statue graces the waterfront, while the popular Marina Bay Sands resort is situated nearby, the combination of which created picture postcard views of this Asian city-state. While many people travel to Singapore for business or vacation, Takeshi Kawamoto ventured here to hone his “warrior” skills.

A “samurai” set on winning

Kawamoto, a competitive swimmer and butterfly specialist, is no stranger to winning. At the qualifying trials for the FINA World Swimming Championships (25m) (Short Course Worlds) in October last year, he won twice—tying the Japanese record of 22.49 seconds in the 50-meter event on one day and setting a new Japanese record on the next day of 49.60 seconds in the 100-meter event*1. The following month, at the FINA World Aquatic Championships, he again took the 100 meters, giving him his first taste of victory on the world stage.

Kawamoto’s main weapon is his dolphin kick, a powerful move where his body, centered on its trunk, flexes to deliver perfectly-timed energy to the tips of his toes, with both legs kicking up and down in unison to propel him through the water. According to former Toyota swim team member Takashi Kishida of the Toyota Sports & Corporate Citizenship Department, Kawamoto’s dolphin kick is either the best or second best in Japan.

However, beyond Japan, Kawamoto views Singapore’s Joseph Schooling to be perhaps his biggest rival, even when it comes to the dolphin kick. Like Kawamoto, Schooling was born in 1995 and competes in the short-distance butterfly, having captured gold in the 100 meters at the Olympic Games Rio de Janeiro 2016. Kawamoto has been keeping an eye on Schooling since their student days and is constantly aware that Schooling is the one to beat among swimmers of their generation.

So when fortune came calling, Kawamoto jumped at the opportunity to take part in the same strength training for swim sprinters that Schooling was to attend. He realized it would be a good chance to pit himself against his rival in high-level training overseas. So—like a samurai set on winning—Kawamoto, not letting his lack of English skills hold him back, went pounding on the doors of a “warrior training hall” in Singapore.

Rivals spur “hate to lose” attitude

Even during practice, Kawamoto always made any swimmer in a neighboring lane his rival. “I hate to lose,” he said. That attitude paid off, making Kawamoto a regular competitor in national swim meets ever since he was in elementary school. He went to a high school and university that both had strong swimming squads, and, at university, while serving as vice captain of the team, he honed his abilities by trying to outdo his own teammates in terms of technique and race times.

Kawamoto has not been alone in his journey. His brother, who led him to swimming in the first place and has since left competitive swimming, is now a physical therapist. However, he still supports Kawamoto, whose swimming career has continued uninterrupted, by periodically checking on his condition. Additionally, Kawamoto’s parents turn up at all of his swim meets in Japan. “What I appreciate about my parents the most is that, even if my [race] times are not good, they don’t say anything. I think that’s one of the reasons I’ve been able to get this far,” said Kawamoto.

Talking about his own personality, Kawamoto said, “I’m kind of a loner. I’ve got a lot of passion and aspirations, but I don’t talk about them much.”

Due to his strongly competitive spirit, he somehow came off to us as perhaps being the kind of person who clearly does not like to talk about his losses, even with members of his family.

When it comes to his own physical condition and mental well-being, rather than leaving everything up to the team’s trainers, he takes his own discerning approach to self-care. It could be said that, after a competition that ends in frustration and regret, it is the person who has fought the battle who most understands the situation and how to deal with it.

As a working athlete

Transitioning into company life as an athlete was not that easy for Kawamoto. Soon after entering Toyota in April 2017, he unfortunately injured his right elbow. The injury required a full two months to heal, during which he could not even get in the water. As he focused on nursing his elbow back to health, Kawamoto took a good look at his situation as a working athlete who belonged to a company. That is when he realized the huge expectations placed on him.

An enormous sense of pressure enveloped Kawamoto, as he soon felt the need to deliver positive results when competing in swim meets. But with such results proving to be evasive, Kishida and other supporters of Kawamoto carefully guided him forward, while repeating the PDCA cycle*2.

Kawamoto says that the kind support provided by others helped him to reset his outlook. “I decided to do my best not just for myself but for the joy of those who support me,” he said. Although progress continued to be slower than he had expected, Kawamoto found time for self-reflection. Eventually, things started to improve for Kawamoto, who was now armed with a new sense of direction as an athlete.

The rival in the neighboring lane

Kawamoto shares the Singaporean training site with some of Asia’s top-notch swimmers, who gather at a pool compliant with international standards, the OCBC Aquatic Centre, Singapore’s best-known, large-scale aquatic sports facility and home to the Singapore Swimming Association.

When we went to see him, Kawamoto had started his day with early-morning training in the pool, followed by out-of-the-water training for the rest of the morning. Now, in the afternoon, he was back in the water for sprint training, along with Schooling and others. Such afternoon training starts with thorough pool-side stretches, after which the swimmers jump into the pool to begin warm-ups. They loosen up by swimming using a kickboard and by doing freestyle at a leisurely pace.

After several back-and-forths across the 50-meter pool, the swimmers exited the water. When the coach announced the rest of the training regime, a sense of tension began to fill the air. Gripping a stopwatch in one hand, the coach paired Kawamoto and Schooling. At the coach’s signal, both swimmers leap from their starting blocks, forming clean arcs with their bodies and slicing into the water.

With strong dolphin kicks and deep strokes, the swimmers build up speed as they do the butterfly. Closer to us is Kawamoto, while Schooling swims one lane over. Each stroke they make creates great waves of water and enormous splashes. The ferocity of the two swimmers makes us almost forget that this is only training.

Rewinding a few years, Kawamoto was inspired by Schooling’s performance in the final of the 100-meter butterfly competition at the Olympic Games Rio de Janeiro 2016. What grabbed Kawamoto’s attention was that Schooling’s swimming made it seem like size was not a factor. In competitive swimming, the shorter the distance, the more a swimmer’s full body length is said to make a difference in the outcome.

Kawamoto, whose physical stature is similar to Schooling’s, said: “I was shocked that Schooling was able to hold back bigger European and American swimmers to take the gold. That stirred up my confidence in believing that I, too, can win.” Schooling’s swimming ignited Kawamoto’s fighting spirit for making the cut for the Olympic Games Tokyo 2020.

Thinking “I definitely want to win (against Schooling)” as he attempted to gain even a fraction of an inch on his next-lane rival, the practice sprint ends, and Kawamoto pulls himself up out of the pool with a feeling of regret. “I haven’t been able to do that,” he said. Such chagrin, however, seems to also be what keeps driving Kawamoto forward.

A calm approach to performance

Kawamoto, who said that he ceases to see those around him when he is concentrating, seems to not pay much attention to other swimmers during a race. While of course focusing on his performance in a real race, he also enters each race wanting to overcome two or three specific issues. “I calmly analyze my own performance, such as which stroke it was that I missed or what point I messed up on, and so on,” he said.

Kawamoto aims for what he calls the “ultimate way to swim”. In contrast to sports like the hammer throw that require a single outburst of power, Kawamoto says his competing time is as long as 51 seconds, during which “several mistakes take place, so I want to know what my time would be if I were able to flawlessly swim all the way to the end.”

Even when it comes to the way he swam when he tied the Japanese record in the 50-meter butterfly at the qualifying trials for the Short Course Worlds last year, Kawamoto said: “I’m not satisfied. I made mistakes,” explaining why he actually feels somewhat glum about his achievement.

Swimming is a sport in which “the results come down to one-hundredths of a second,” said Kawamoto. “Some swimmers are strong at starts. Others start to close in and overtake in a race’s latter half. There are all kinds of strategies. And some swimmers just fade out near the end, so you really don’t know the result until everything is truly over,” he added.

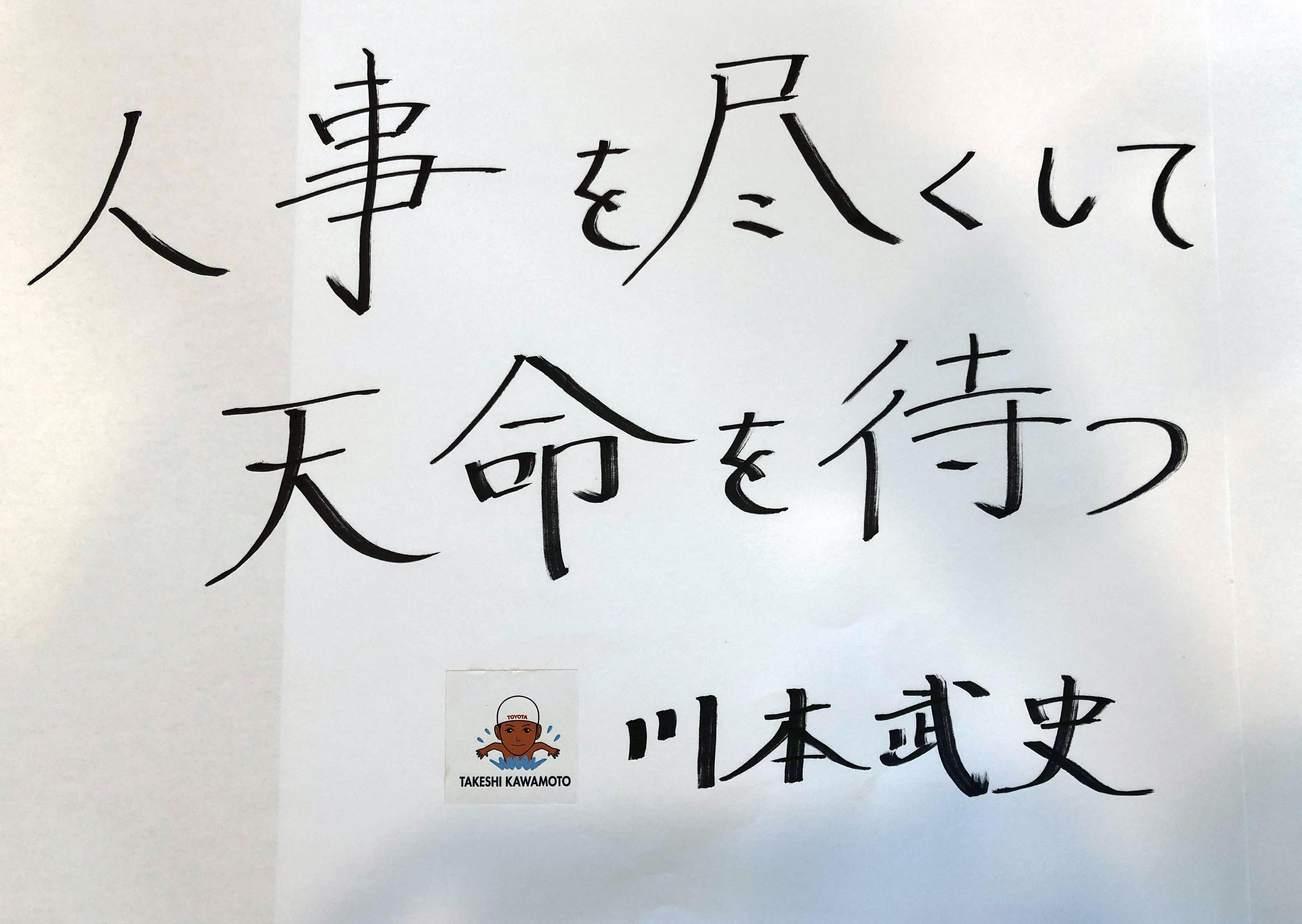

Kawamoto’s motto is: “Do your best and let the heavens do the rest.” His approach of doing what needs to be done and then seeing what fortune brings, along with his way of honestly addressing issues at hand, gave us a keen sense of his drive and determination. Going beyond giving it his utmost, just as it is sometimes said that luck plays a part in any victory, Kawamoto’s desire to have fortune on his side deeply impressed us.

Kawamoto’s unrelenting determination to best his rivals increases his motivation and has enabled him to steadily become a better swimmer. With his sights constantly fixed on the next stage up, he is now thrusting ahead toward his next big goal of winning a medal at Tokyo 2020. In the fashion of “Start Your Impossible”, it can be said that, for Kawamoto, this means taking up the challenge of not only beating his rivals from around the world but also beating himself.

As it is in some other countries, swimming is a popular spectator sport in Japan, as well. We imagine that the swimming venue at Tokyo 2020 will find a full crowd cheering on the top swimmers from around the world. We look forward to cheering on Kawamoto with all our might as he not only brings out the maximum in his power and technique but as he also puts fortune on his side.

Editor’s note

The word that was etched into our consciousness the most throughout our interview with Kawamoto was “winning”. Even after his training session that we went to watch, Kawamoto was burning with fight in his eyes as he said, in reference to his nemesis Schooling: “I’m not going to lose!” For Kawamoto, a rival is one who constantly makes you want to try harder. Even though it was just training, we sensed that Kawamoto was fully enjoying going up against his most-admired rival.

*1Short-course swimming features pools of two different lengths—50 meters and 25 meters. As the number of turns needed to complete a race varies for each length of pool, official records are separately recorded for each pool length.

*2A four-step method cornered on activities related to “Plan”, “Do”, “Check”, and “Act” that is regularly used in Toyota workplaces to improve operations