A special project team worked on reviving a Toyopet Racer, Toyota's first racing car from over 70 years ago. The ninth article in this series recounts the journey of creating the suspension and related components.

This series features Toyota’s project to revive a legendary racing car—now on display at the Fuji Motorsports Museum—with a look at the project members’ efforts as well as the history and meaning behind the vehicle.

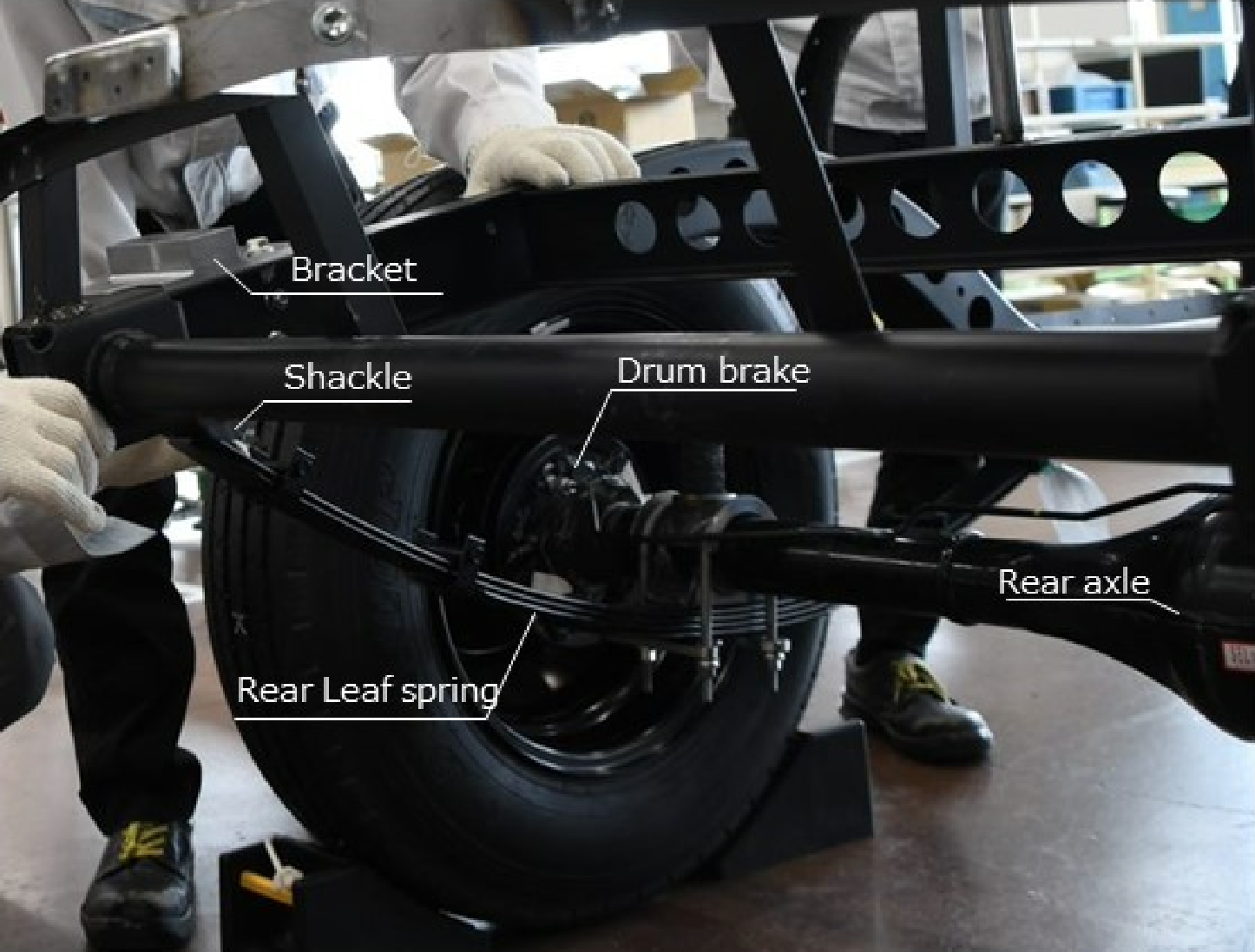

This ninth article focuses in two parts on the efforts of team members responsible for the suspension and related components that handle the car’s basic functions – driving, turning, and stopping. Here in Part 2, we share how deciding on brake specifications led to discussions involving every member of the restoration project team, and track the various parts from design to final assembly.

Brake specs spark heated debate

Part 1 of this article focused on the difficulties in determining specifications for the Toyopet Racer’s suspension, a major hurdle that had to be cleared before design work could begin.

Besides the suspension, however, the same team was also in charge of another key component that underpins the “stopping” side of a car’s three basic functions: the brakes.

As it turns out, the brake specifications had been finalized even before those of the suspension, through a series of heated discussions involving the entire restoration project crew.

So, let’s start by taking a step back chronologically to look at those debates on brake specifications.

These major discussions centered on the concept and safety of the machine being restored. Although inconceivable in modern cars, the original Toyopet Racers were equipped only with drum brakes on the rear wheels; that is, they had no front brakes or emergency brakes.

Ding Nan

The Toyopet Racer was developed for racing in the particular environment of an elliptical dirt track. It’s likely the brakes weren’t even used during races. The front and emergency brakes were probably omitted to reduce weight.

Making cars as lightweight as possible is the golden rule for winning races. The team members gained insight into the original designers’ extraordinary commitment to reducing weight.

Daichi Sugimoto

We had fierce debates among the entire restoration project team over rebuilding the car without front and emergency brakes. Wouldn’t that be dangerous to test drive? Aren’t they necessary for safety reasons? Some worried that an accident could spell the end of the whole project. The discussions often ended in a deadlock without any consensus.

The decision was made to sound out individual members about their thoughts on the project. This process confirmed that, as a whole, the team was keen to remain faithful to the original creators by restoring the machine as close to the original as possible.

From this foundation, the members considered ways to ensure safety without front and emergency brakes.

Following these lengthy discussions, the team ultimately settled on adhering to the original design, with only rear-wheel brakes. At the same time, the vehicle’s performance was used to estimate the braking distance, while run-off areas and speed limits were set for the test course.

To further improve safety, it was agreed that the trial runs could only be conducted by those who understood the Toyopet Racer’s unique braking setup and had familiarized themselves with the manual outlining how to respond in the event that something went wrong.

Aiming for the original vehicle stance, ride height, and feel

With the suspension and brake specifications finalized through heated debate by the entire project team, the four members could now get started on designing and fabricating the necessary components.

As outlined in Part 1, the team tasked with designing and fabricating the suspension had another major objective besides ensuring the strength necessary for safe driving: to achieve a similar look, ride height, vehicle stance, and feel to the original Toyopet Racer.

Unfortunately, none of the four had any experience in suspension design. Indeed, even the process of designing car parts with 3D-CAD software was a new undertaking.

Sugimoto

I hadn’t touched CAD software in a long time, since the initial training I received upon joining the company. Naturally, I had no idea how to design the suspension or the relevant parts.

Thankfully, the company has manuals outlining the suspension design process. With the other members, we studied those manuals and took our time preparing the designs, drawing on advice from the veteran advisers we call oyaji.

The suspension was redesigned to give the restored Toyopet Racer the same ride height and feel as the original.

Suspension systems are complicated, with many moving parts, and their performance is greatly affected by the positioning and method of installation.

To achieve the ride height of the original Racer, the team figured out the required camber (amount of bend) for the leaf springs from old photos of the vehicle.

And when it comes to replicating ride feel, the key lies in the hardness of the front and rear suspensions. To determine this, the team had to obtain the load values for the front and rear axles—another task that proved far from simple.

These values were not mentioned anywhere in the records. To compute them from scratch, the team had to estimate the weight and center of gravity for all the components we introduced, from the engine and body to the steering wheel and seats.

Sugimoto and Ding asked the members in charge of each component to come up with estimates for weight and center of gravity, then calculated the load values. From there, using spec sheets for the Model SD base vehicle as a reference, they settled on the hardness of the Racer’s suspension.

Finding the right materials was not smooth sailing

Even with the parts design finally finished, the suspension team could not move straight onto production as intended. When consulting the base vehicle’s blueprints for information about materials or how the parts were made, they found that some of those materials were no longer in use.

Sugimoto

The leaf springs, for example, were made from different materials from those of today.

While we wanted to reproduce the original vehicle as closely as possible, making the leaf springs exactly as they were would be prohibitively expensive and time-consuming. So, we had to change the material. It was a tough choice.

Meanwhile, to use current materials, we needed to revise the dimensions by a few millimeters. These small changes required slight adjustments to other parts as well, and ultimately things didn’t match up. The problem couldn’t be solved by simply fixing the dimensions, so we had to make new designs.

As it happens, the leaf spring brackets that I oversaw also had to be modified, and I built them from scratch with the Land Cruiser design as a guide.

To begin with, the team couldn’t even tell what was meant by the codes that stood for materials on the drawings. The task of identifying these materials and selecting alternatives was taken up by Shinya Omura, who joined the team as the specialist in this field.

Omura

On the blueprints for the base vehicle, the materials are noted as codes, but these differ from the JIS codes we use today. We tried to decipher them one by one, but some were unknown even to the veterans we consider our “walking materials encyclopedias.” Even once we identified these materials, we had to figure out the appropriate heat treatment.

We looked up old materials archives to find out what kind of steels they used at the time and how they were heat treated, considering the methods we could employ for today’s materials. It was a process I had never been through before.

In fact, Omura handled this work of “deciphering” materials from drawings not just for suspension-related components, but for any parts where it was needed.

And so, with assistance from Toyota’s oyaji and others outside the company, the four-person team was able to move forward with procuring and producing parts.

Dedication extends to brakes

Meanwhile, Ding was in charge of designing the sole brakes for the rear wheels. She worked towards the required braking force and a comfortable feel through continued trial and error. This was necessary because the original Racer lacked the vacuum servo that boosts braking force.

After the rear axle was adapted from those used in minivehicles, it was decided that the drum brakes would also be likewise borrowed.

But since these were not designed for the Toyopet Racer they were too small and could not ensure sufficient braking power without modification.

The only way to guarantee adequate power was to boost the pressure transmitted to the wheel cylinders that press the brake pads against the drums, which included increasing the brake pedal ratio.

Ding

I decided to increase the hydraulic pressure on the brakes and searched for small master cylinders capable of doing that, but even the smallest ones I could get my hands on did not give us the performance we were after.

At this point, one of the oyaji suggested I try a clutch master cylinder.

Even with that, we still lacked power, so I met with the body team who were designing the brake pedal and asked them to modify the pedal ratio. This gave us a result we were happy with, both in terms of power and feel.

Gaining confidence and connections

Thanks to the efforts of all four team members, the suspension and brake parts were finally completed and ready for assembly onto the frame. Yet even this stage of the process brought challenges.

Sugimoto

The other teams’ assemblies, test runs, and other milestones had been scheduled, and any delay on our part would cause them trouble. We worked under that pressure every day.

Takahiro Tashiro

When we tried to mount our finished parts on the ladder frame, all the minor dimensional errors and slight deformities due to welding or other machining process added up, leading to misaligned holes that made the job impossible. This happened multiple times, making it very tough.

Our team was on site practically every day, working on parts that needed to be fixed.

Despite their lack of experience and expertise in suspension and brake design and fabrication—and the unforeseen extra work of estimating component strength and specifications—the four-person team somehow managed to complete their assignment on schedule. So, what did they each take away from the experience?

Sugimoto

Every team member performed really well under tremendous pressure. As the leader, I’m grateful for that above all else.

This project was about having a concrete objective and continuing to find ways to get things done, instead of reasons to give up. I learned anew just how important these two aspects are when it comes to work. I want to keep that perspective in my work moving forward.

Tashiro

Right from the start of the project, I was most interested in how engineers made cars in those days, and I think we found the answer by challenging ourselves to use the same manufacturing methods.

It was also a great experience in terms of meeting and making new connections with many people from other departments.

No matter how busy I am with regular work, I want to be a part of any such projects like this in the future.

Omura

One of my big takeaways from this project was the new connections with many different people, both inside and outside the company.

I learned that both at Toyota and beyond, there are many key individuals who will work with you to find solutions if you ask for help. Every day made me realize how important such connections are in the workplace.

This experience also brought home the importance of observing and considering things carefully. And above all, I saw firsthand that, ever since the days of the Toyopet Racer, our job has always been to bring happiness to others.

Ding

For this project, we made virtually all the decisions and carried them out ourselves, from setting performance targets to designing parts.

In entrusting us with so much responsibility, this project felt like a small step towards becoming an engineer knowledgeable in both hardware and software.

From design to production, I recognized the importance of communicating with different departments inside the company and outside suppliers. I was able to establish personal contacts and gain an appreciation for Toyota’s strength in manufacturing.

I hope to maintain these networks and continue utilizing them in my work.

With this experience under their belts, the four members have already embarked on new challenges. The project to restore Toyota’s first racing car is already contributing to the future of carmaking.

Next time, in the tenth and final installment we unveil the fully-restored Toyopet Racer and take it for a test drive.

(Text: Yasuhito Shibuya)