A series showcasing Toyota's research in non-automotive fields. This time, Toyota tackles farming.

“The improvement was unbelievable!” remarks an astonished farmer.

“Agriculture is ripe with potential,” points out Chairman Toyoda (then president) with delight.

In this article, we meet a farmer who has incorporated Toyota’s kaizen (improvements) into his operations. What was it that got him so excited?

Daily fieldwork

In the city of Yatomi, Aichi Prefecture, Toyota employees would go to work every day in these vast fields.

They had embarked on a project to see if the concerns of local farmers could be solved with the Toyota Production System (TPS). Underpinning these efforts was the company’s philosophy of acting for the benefit of “someone other than yourself.”

Tatsuya Hirai, Senior Expert, Agriculture & Biotechnology Business Div.

We set out to help boost agricultural productivity by applying the production management methods and process improvement expertise we had cultivated in the auto industry.

We began by emphasizing communication with the farmers, making gradual improvements based on concerns and ideas from the genba. I feel that we created a virtuous cycle that made the farmers’ work easier and gave us the pleasure of becoming a trusted partner.

Toyota takes over the farm?

Initially, however, Toyota’s offer was met with skepticism on the part of the farmers. Nabehachi Nousan, one of the largest rice growers in Aichi Prefecture, is a second-generation farm run by Kiharu Yagi.

Kiharu Yagi, President, Nabehachi Nousan

They said they wanted to contribute to agriculture, but I wondered, “Why Toyota?”

As they started coming in each day with laptops in hand, my father, who ran the farm before me, became alarmed that “Toyota is trying to take us over!” (laughs)

Nabehachi’s rice paddies are scattered around a large area alongside those of other farmers. Attempts to manage the fields using maps led to some close calls…

Yagi

New employees who are unfamiliar with the area sometimes get mixed up and almost end up planting in neighboring fields. The same nearly happened with the fall harvest—we were one step away from stealing. (laughs)

Personal experience has long been a key factor in the running of farms. This left a great deal of room for TPS-driven improvement by quantifying and visualizing every aspect of the job.

Making a splash with shovel storage

In Japanese, the character for “rice” (米) is a combination of those for “88” (八十八), and it is said there are 88 steps to growing the crop. To aid this process, President Yagi embraced Toyota’s improvements.

Even so, there were many clashes of opinion. When the Toyota employees searching for potential improvements questioned why things were done a certain way, they were often told, “Because that’s how it’s always been done!”

Before long, however, the work grew noticeably easier to carry out and manage.

Yagi

It was fascinating to see how quickly results appeared. For example, our shovel storage was a mess. It was common for employees to go off looking for shovels and not return.

The solution was to number the shovels and make sure they were put back in their designated places. Just by doing that, we instantly eliminated the wasting of time.

Toyota’s kaizen efforts continued to yield interesting results.

Seeding work made a whole lot easier

Spreading seeds was once an arduous task, with workers stooped over the benches. Raising up workbench legs dramatically eased the physical demands, helping prevent back pain among employees.

Less seedling waste, more sources of revenue

The farm was making too many seedlings, with surpluses being discarded. After carefully analyzing production, the number was halved from 30,000 to 15,000, greatly reducing waste. The freed-up greenhouse space was used to grow other crops, with a positive impact on both the environment and management.

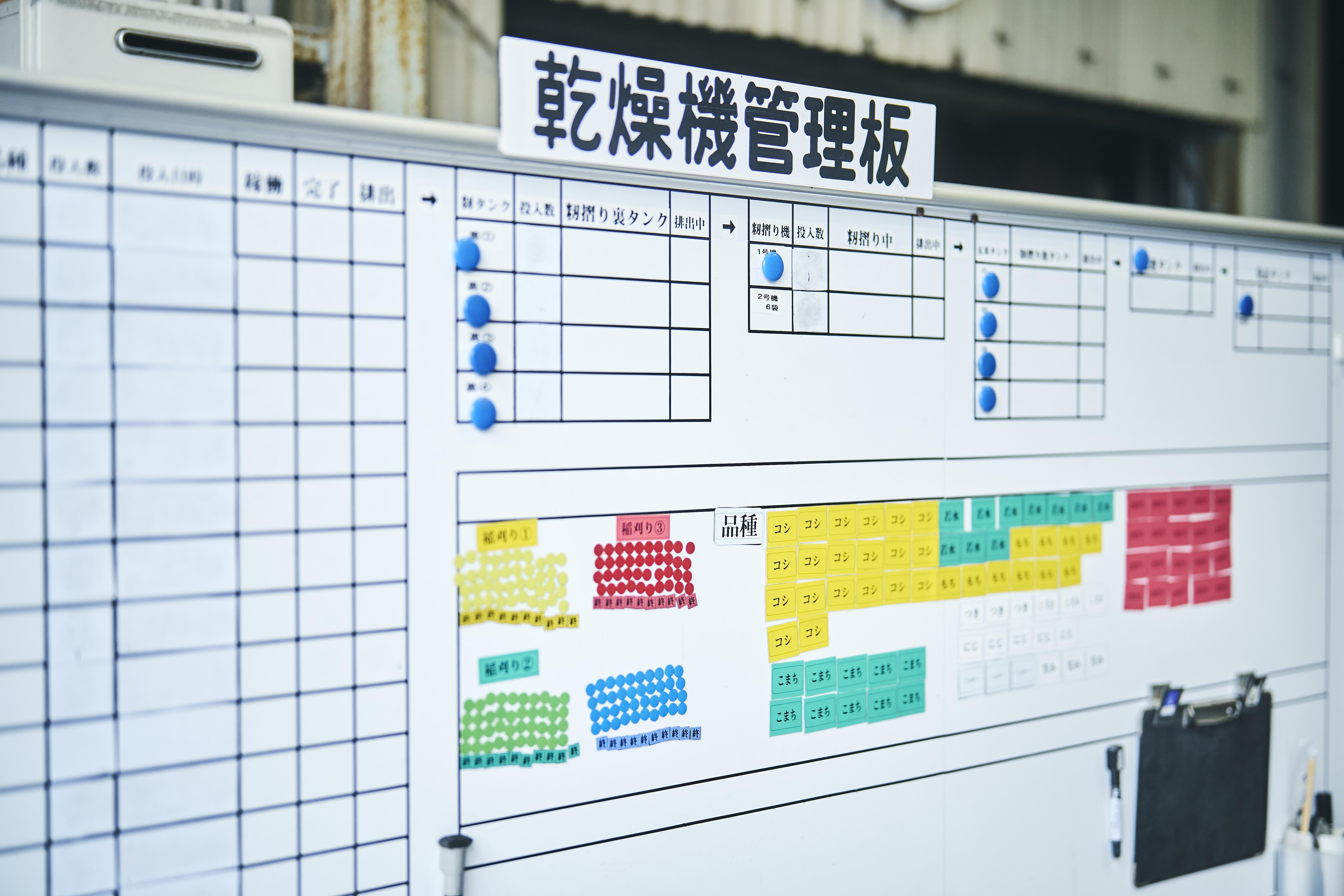

Halving work time in the drying process

Rice was being harvested without keeping track of drier capacity, causing the unhulled grain to pile up. Long working hours had also become the norm. Using a board for visualization streamlined the process, halving the required working hours from 1,750 to 800. Workers can now enjoy proper time off even during the peak season.

Eliminating waste, inconsistencies, and unreasonable requirements

The annual work plan, previously organized in notebooks, was written out on a board for all to see. Having the production schedule clarified eliminated wasteful and unreasonable tasks, and evened out inconsistencies in quality.

Skill map spreads workloads, reduces risks

Another board was set up to show the work that each person can handle. This stops individuals from offering misleading instruction on tasks they aren’t qualified to teach. It also develops talent by motivating employees to master multiple skills. By evening out individual workloads, this approach also reduced the risk of creating backlogs.

Yagi

Plowing a rice field might take one person 10 minutes, and another 40. In the past, the slower ones would cop an earful.

At first I thought, “Why even it out? Let people do things their way!” But when we made the manual, it turned out that the speedy ones had just been cutting corners, and the slower folks were actually the benchmark. (laughs)

“Visualizing” the farm’s operations also highlights the issues, allowing improvements to be made. These white lines, for instance, were another kaizen idea.

Though proposed by Chairman Toyoda (then president), the purpose of such markings would be known to many who are familiar with Toyota’s genba.