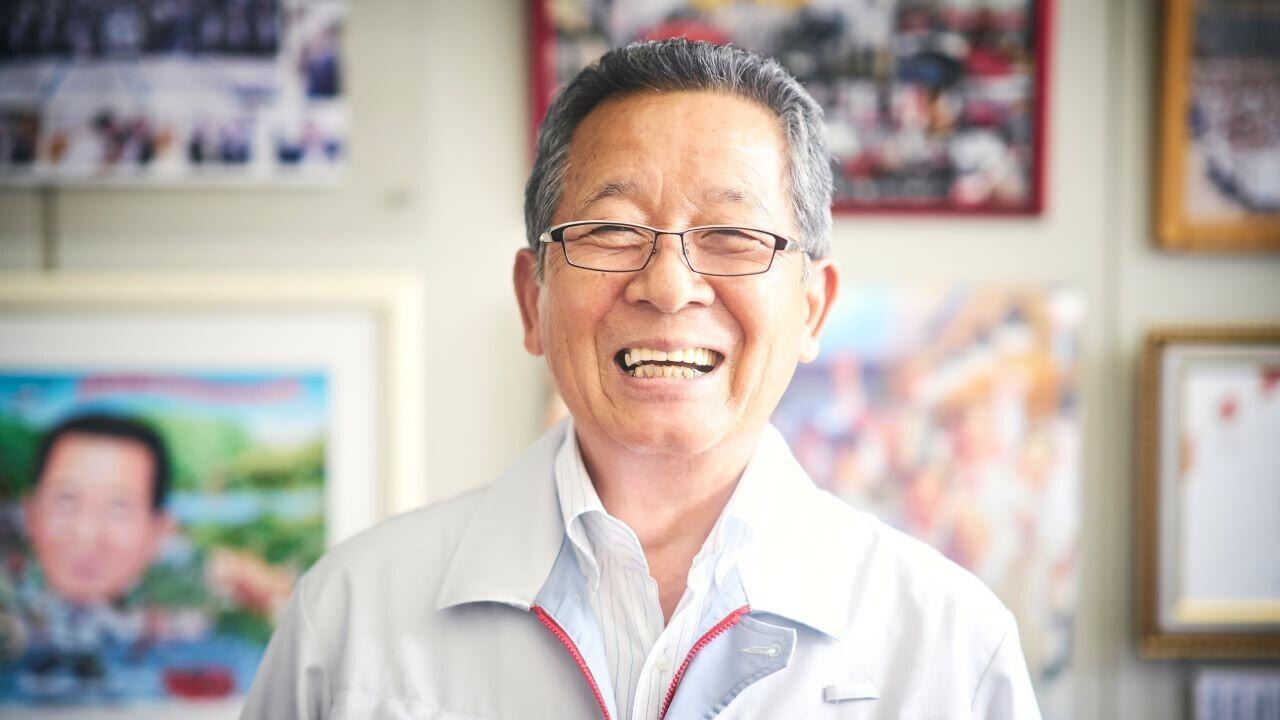

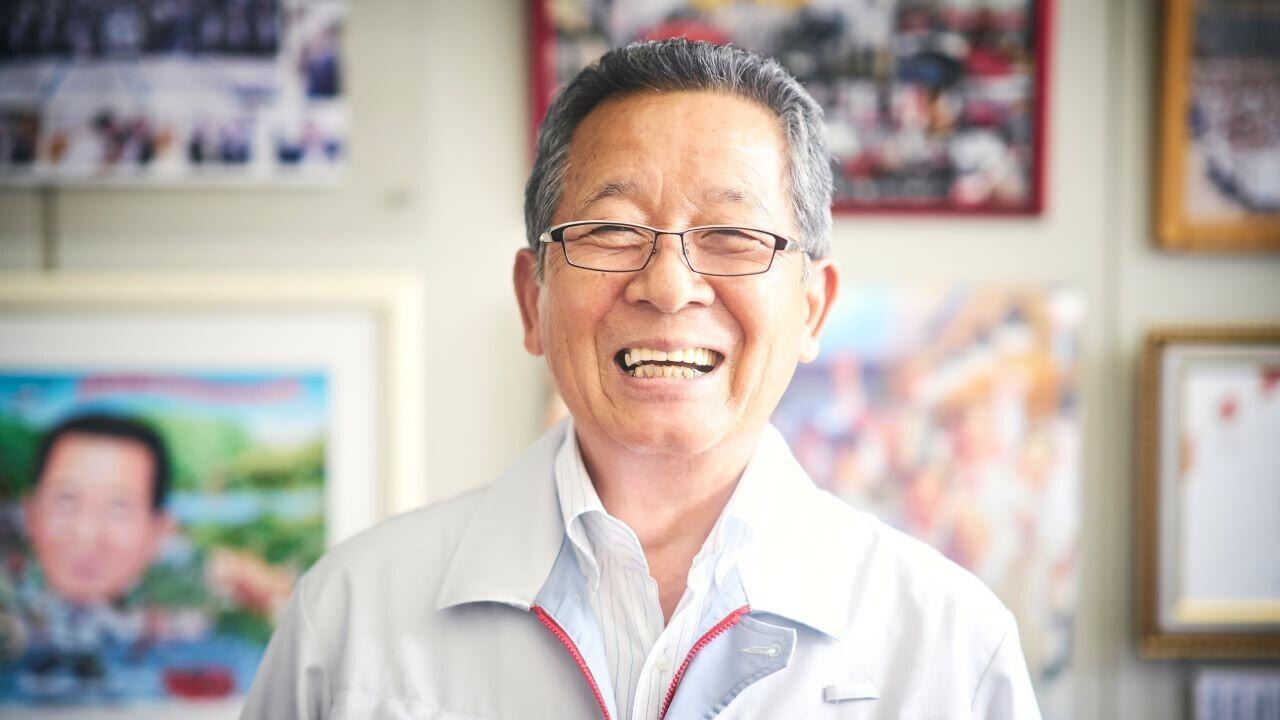

This series highlights top submissions from Toyota's Creative Idea Suggestion System. In a special interview, we spoke with Executive Fellow Mitsuru Kawai, known as Oyaji Kawai, who has spent his entire 62-year career at the genba.

“If you want to know about the Creative Idea system’s 70-year history, you should speak to Oyaji Kawai.”

This was the advice we received from Toyota’s TQM Promotion Division while trying to get this series off the ground and searching for people to talk about the Creative Idea Suggestion System.

We promptly sought out Oyaji Kawai, but as the interview progressed it became clear there was a great deal that he wanted to share and pass on. In this special article, we bring you our conversation, including:

・How creative ideas and other kaizen activities become deeply rooted as part of Toyota’s DNA, starting from the first lessons at the company’s training academy.

・How the Creative Idea Suggestion System is closely linked to personnel development.

・The key role it plays in improving practical problem-solving skills in the genba.

・How the system spurs a virtuous cycle, not only improving efficiency but also giving workers a sense of satisfaction and accomplishment that inspires further improvements.

・And how small improvements combine to achieve major transformations.

Here is Oyaji Kawai in his own words, reflecting over 60 years of experience.

Toyota’s building blocks

I’m now in my 63rd year at the company, having gone straight from junior high school into the Toyota Technical Skills Academy. This was before the high school course. The first thing I learned in the classroom was how to submit creative ideas.

In those days, Toyota Motor Corporation had no money, no facilities—nothing—so we were taught to rely on our ingenuity.

Those ideas earned rewards, and if you wrote them out correctly and quantitatively, you would score higher and receive more money. Older students taught us how to write the submissions.

One type of creative idea is how to eliminate obstacles and create straight walking paths. Instead of writing that you cut five steps down to three, you would note that one step is equal to half a second and then calculate the efficiency gain. That’s what we were taught.

A big part of Toyota is kaizen, or continuous improvement, which stems from the creative ideas put forth by individuals. Put together, small ideas lead to major improvements, without which we would not have innovation, or the Toyota Production System. Creative ideas are the building blocks of Toyota and our starting point.

More than monetary rewards

In my younger days, I would compete with coworkers and submit some 50 or 60 creative ideas a month, earning more in rewards than overtime pay. While the monetary rewards were part of it, what made me happiest of all was colleagues saying that my improvements were really good and made their work easier.

Back then I was on the day shift, and whatever improvements I made would be put into practice by the night team. I would go in the next day excited to hear their feedback.

But after becoming plant manager, I was mostly busy scoring the ideas suggested by my staff, who even spent their lunch breaks and time off competing with each other (laughs).

In the past, we used to set up days when we would show family members around the workplace. One of our staff had a finger impairment, though they did all the same work as everyone else. When his wife came in, she asked, “What’s up with this sintering feed slide?”

We were astonished that she knew such technical terms, and it turned out that when the husband was having a beer at home, she passed the time by filling out his creative idea sheets for him. Apparently, they split the reward money between them.

Before long, she had learned all the technical terms and told him, “You can buy drinks with whatever you earn from creative ideas, after I take a cut for my work.” She told us it was fun for her too. These kinds of things happened (laughs).

Where slackers find success

One thing you notice when you have staff working under you is that those eager to find creative ideas will improve. They have a keener eye for problems. It also helps to be a slacker, because then you look for ways to make life easier and get the job done quicker.

Doing things half-heartedly is just lazy, but getting the job done right and quickly requires a lot of thought. And you don’t gain any insight by simply doing as you’re told.

There is nothing more tedious than simply doing what you’re told. That’s the worst misery.

Only people who don’t engage in kaizen speak of “the usual way” or how things have always been done. It’s no different to responding with “Be quiet!” when a child asks, “Why? Why?” That is the reason newcomers are more likely to question how things are done.

If you don’t know something, ask. Go find out about the processes that come before and after. The people who do that get better, and their staff look up to them. That’s education.

The importance of a supervisor’s attitude

That said, young staff aren’t able to make difficult improvements. Even if it’s just a tiny suggestion that slightly improves the process of transferring documents from one place to another, supervisors should take it seriously and say, “Good idea!” If they don’t show that kind of attitude, the ideas will stop coming.

Even if you think it seems likely to fail, let them try once. I rarely ever say no. No matter what someone might suggest, I tell them, “Sounds good, let’s try it and see!”

Some say the young kids are quieter these days, but they don’t have any less energy than people did in the past. The question is, how do we harness that energy, how do we make work more interesting for them? We enable them to make improvements, share in their joy, and allow them to gain a sense of accomplishment and satisfaction.

Such things form the DNA of Toyota’s genba, and it’s vital that we continue them.

What efficiency and productivity figures mean

When a task can be done easier and faster, the result is greater productivity. We certainly don’t set out to work harder. When you mention the Toyota Production System, people think we are bound by efficiency targets and constantly hounded about productivity. But even though we talk about numbers, it is not just about the figures. It’s about making improvements and raising the bar higher.

For example, let’s say that our target for this year is to improve production efficiency by 3%. If the department has 100 people, and we remove three but still do the same work with 97, our individual productivity will increase. To accomplish that, we need to think about how we can do the job with 97 people. You don’t just panic and go for it.

“Let’s do this in two steps instead of three.”

“Can we do that task with two people instead of three?”

“If it’s too heavy to move, let’s come up with a karakuri system to make it easier.”

“We should draw up instructions so that this can be done simply without relying on instinct and intuition.”

We constantly make these small improvements, with the numbers acting like a target indicator. You don’t start with productivity percentages, but rather by figuring out how to do the job with three fewer people, so you can reach that 3%.

From the outset, the goal has to be about making life easier for people. If it’s only about raising efficiency or making improvements to reduce the company’s costs, it doesn’t work. That’s not it. The improvements have to come naturally.

For example, say a newcomer is always getting his knees dirty when performing a standard task. Give him a hint by asking why and where they get dirty. That leads him to notice that he always kneels down when assembling a part. He also notices how individual movements make his work harder. If he eliminates them, the job becomes easier.

With the right hints, people will make the improvements on their own.

These improvements are made in the workplace so that, even if personnel change, the next person can continue to do the same thing. The process repeats over and over, and as people move up in positions and expand their areas of work, the effect is that much greater.

Helping the virtuous kaizen cycle to grow

The groundwork is done by the individuals who come up with creative ideas. From there, we go a bit bigger with our QC circles (creative idea kaizen activities in small groups), making improvements and solving problems.

Pursuing creative ideas sparks communication, as senior colleagues and supervisors offer feedback: “Try it a little more like this” or “Now that you’ve gone that far, maybe we can do this too.”

At Toyota, we talk about “continuous kaizen.” It doesn’t end with a one-off improvement but keeps rolling on, getting bigger and bigger.

Many people outside the company ask me, “Why are you all so good at making improvements?” I don’t have an answer. For us, that is just the world we live in. But saying as much to people outside the company might come off as arrogant.

I am sometimes also invited to give talks or visit a production plant, but instead of pointing out where people are wasting effort, I try a different angle: “Let’s do this together!” That approach goes down incredibly well. People come to realize something:

“You mean we just need to do these simple, everyday things?!” When people realize that this is kaizen, they start to believe that they can do it too.

Improvements surprise people and make everyone happy. This encourages them to keep going and makes the job more rewarding. Everyone’s work becomes easier, and efficiency goes up.

Memorable ideas

Which creative ideas made a strong impression on me? That list is endless.

That’s because our plants are constantly evolving. Every time I visit, people proudly show me what they’ve done: “Oyaji, come look at this!” They’re very keen to show it off (laughs). But the ideas really are well thought out, and I’m always amazed.

Our circumstances and environment are constantly changing, and that’s when creative ideas have the greatest impact.

Even if we want to pursue automation, we need to ensure that work performed by human hands is done safely and at a high quality. Once you get a task to a point where anyone can do it, then you can give it to the robots. Trying to automate before that doesn’t work.

Automating a difficult task ends up being complicated, with sensors all over the place. As it becomes more complex, the process becomes a black box, which you can’t fix when something breaks down. You could spend three months training up on it with the manufacturer, but in another year, they will come out with a new product.

Even in the case of AI, it becomes a question of who trains the machines. For areas like painting and welding, we bring in people who can do the job better than robots to transfer their skills. If the person teaching cannot write neatly, neither will the robot. To make it write well, you have to write well yourself.

If we reach the point where AI does everything, we will lose our competitiveness. Then we need people who can teach it to be more efficient. When everyone is using three machines to make one product, there is no competitive advantage. Kaizen is about finding ways to do it with two. If getting down to one machine is impossible, make the two machines twice as productive. There are always more improvements to be made.

To reiterate what I said earlier, without improvement there is no innovation, and no Toyota Production System. That kaizen spirit is also what allowed me to grow. It all stems from creative ideas.