Part two of the final race of the 2021 Super Taikyu Series will take an overall look at how the race represented this year's challenge for carbon neutrality in the areas of "making," "transporting," and "using" hydrogen.

On November 13 and 14, the final round of the Super Taikyu Series was held at Okayama International Circuit in Mimasaka City. Part one discussed the evolving circle of like-minded partners, with a gaze focused on next season.

Part two will take an overall look at how the final race represented the challenge for carbon neutrality in the areas of “making,” “transporting,” and “using” hydrogen.

“Making”: The hydrogen of Fukuoka City, created from sewage

The hydrogen used as fuel for this race has come not only from the sources which have supplied Toyota with hydrogen previously—Obayashi Corporation (from geothermal energy), Toyota Kyushu (from solar power generation), and the town of Namie in Fukushima Prefecture (from solar power generation)—but also from sewage biogas supplied by Fukuoka City for the first time.

Having focused on the potential of hydrogen from an early stage, Fukuoka City began its endeavors as a member of Fukuoka Strategy Conference for Hydrogen Energy, set up in 2004 as Japan’s first industry-academia-government organization collaboration in the domain of hydrogen. Starting the Hydrogen Leader City Project in 2014, the city has carried out many of Japan’s first-ever hydrogen verification tests, as part of a vision of making the “hydrogen society” a reality.

From March 2015, Fukuoka City has been engaged in the first project in the world aiming to produce hydrogen from public household sewage at a water treatment plant, and supply it to fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) via hydrogen stations installed within the same facilities.

The biogas generated during the sewage treatment process is 60% methane (CH4) and 40% CO2, and hydrogen can be obtained by removing the methane using membrane separation equipment and reacting water vapor (H2O) with the CO2. The CO2 is recovered in liquid form and used for the indoor cultivation of vegetables.

This system allows hydrogen to be produced in a stable manner, as sewage arrives at the plant each day. Furthermore, if it becomes possible to create hydrogen from currently unused biogas at sewage treatment plants all over Japan, this will support local production for local consumption in the energy domain.

The hydrogen manufacturing capacity is 3,300Nm3 for 12 hours of operation per day, enough to power around 60 units of Toyota’s FCEV Mirais. Approximately 20% of the hydrogen prepared for the qualifying round of the race on this occasion was supplied by Fukuoka City.

Masashi Tomita, manager of the Business Startup & Investment Promotion Department of the Fukuoka City Economy, Tourism and Culture Office expressed enthusiasm for the hydrogen project, saying, “We have worked to build partnerships in hydrogen over the past 10 years or so, but it is in the last few years that we have really seen the expectations towards hydrogen increasing in the world at large. We have formed more partnerships through this race, and intend to deepen this industry-academia-government collaboration as we take on the challenge of making the ‘hydrogen society’ a reality in our quest for carbon neutrality.”

“Transporting”: Adapting the Mirai’s tanks to improve transportation efficiency

The hydrogen supplied on this occasion was transported from the various production sites to Okayama, with the use of biofuel from Euglena. The “transportation” aspect has also been taken into consideration in the move towards carbon neutrality.

In the previous race at Suzuka Circuit (Mie Prefecture), the hydrogen had been transported by a small fuel cell truck through a partnership between Toyota and Commercial Japan Partnership Technologies (CJPT). However, this process was inefficient, with 7kg of fuel being used to transport 15kg of hydrogen over 100km.

The reason for the inefficiency lay in the heavy weight of the metal tank for hydrogen transportation, and the limited number of units that could be loaded onto a small truck. Also, the filling capacity per unit was limited due to the level of pressure allowed for the tanks.

Work is underway to resolve this issue by utilizing carbon fiber reinforced plastic (CFRP) tanks with resin liners developed for the Mirai. Such tanks are lightweight and can move the hydrogen at high pressure.

Traditional metal tanks added a weight of 1.7 tons per curdle (bundle of cylinders). With a small truck only able to carry 3 tons in total, this meant that two curdles could be not loaded.

Meanwhile, the new CFRP tanks with resin liners add a weight of only 1.35 tons per curdle, amounting to only 2.7 tons when two curdles are loaded onto a truck, and fitting the width of a 1.7m-2m truck.

Furthermore, whereas the metal tanks could only bear 15MPa of pressure, the new tanks can withstand up to 70MPa.

As a result, it is now possible to transport over 80kg of hydrogen at one time, 5.5 times more than the previous amount, allowing for a more efficient transportation process.

Although CFRP tanks cost more, “If they start to be used more with commercial vehicles and undergo standardization [based on size] as seen with dry cells, everyone else will also be able to use them, and the prices will go down,” said CJPT President Hiroki Nakajima. Hopes are high that these challenges will be overcome going forward.

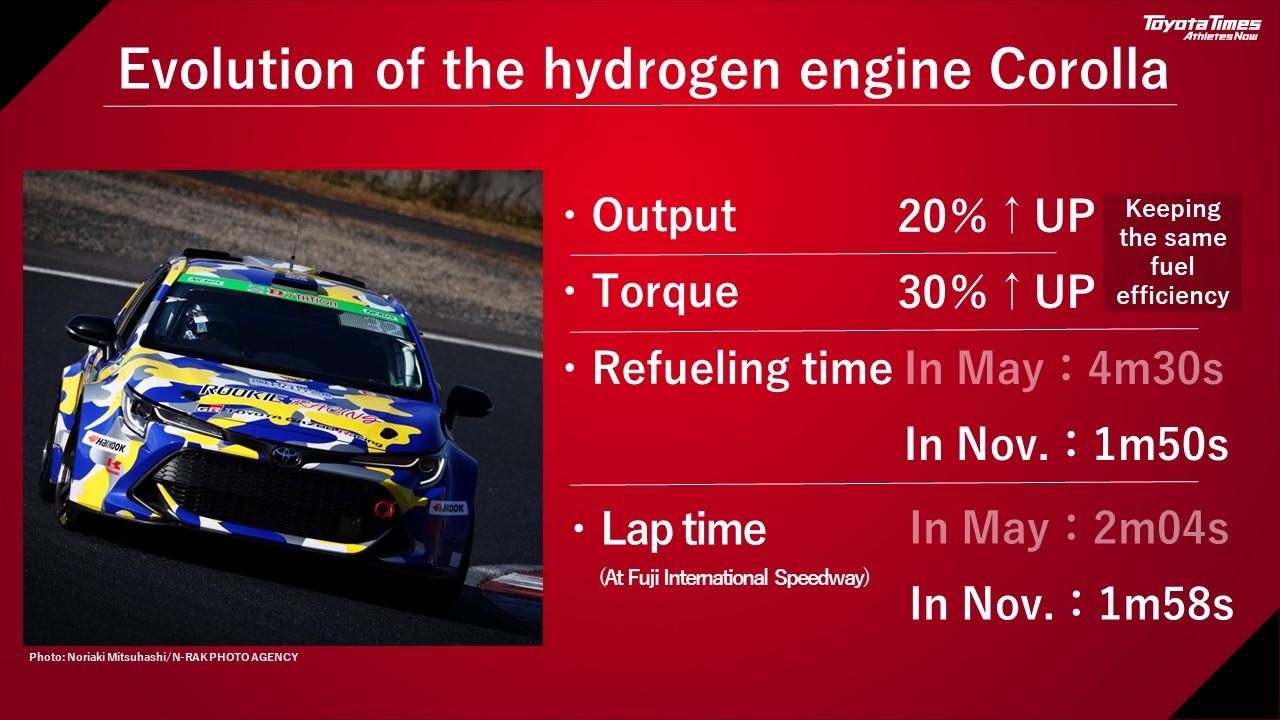

“Using”: Maintaining fuel economy while boosting output 20% and torque 30%

Over the past three races, the engineers have expeditiously improved the performance of the hydrogen-powered engine within the tough environment of motorsports.

“We’ve raised the performance level of the engine mainly for improving combustion through painstaking tuning like the hydrogen injection method. Generally, boosting the power level means poorer fuel economy, but we managed to maintain the same level of fuel economy as that we had at Fuji Speedway in May, while largely increasing the output. The engine is really in very good shape,” says Tomoya Takahashi, manager of the GR Project Operation Division.

Over the six months that have elapsed since the 24-hour race at Fuji Speedway back in May, output has risen more than 20% and torque by more than 30%. This means the car has finally achieved a level of performance exceeding that of gasoline-powered engine vehicles.

Meanwhile, fuel economy, which is generally traded off for output, has been successfully maintained. Assuming the same level of output as that seen in the Fuji Speedway race, means an improvement of around 20% in fuel economy.

Furthermore, the time required for hydrogen refueling, which initially took 4 minutes and 30 seconds, has now been reduced by 60% to just 1 minute 50 seconds, through raising the boost rate.

“Raising the pressure level in the tank creates heat, but we’ve worked to boost speed while monitoring the temperature to ensure safety,” says Takahashi, disclosing a vital key to the process.

Although the hydrogen engine has undergone various improvements, it is critical to reduce the number of pit stops in order to win races.

Looking ahead to the next goal, Chief Engineer Naoyuki Sakamoto of the GR Project Operation Division says, “We need to increase the car’s driving range. We will reduce the weight of the vehicle, and further improve the car’s performance as a whole. This is important not only for hydrogen-powered engines, but also for other powertrains, including battery electric vehicles (BEVs) in order to expand the options for carbon neutrality.”

Meanwhile, Sakamoto hinted at the possibility of improvements for racing performance saying, “The way the tanks are now (i.e., their shape) is not good in terms of volumetric efficiency. They can be made more efficient with increased freedom in their shapes. In order to have things ready in time for this year’s race, we used Mirai’s tanks which we have sufficient experience in, but for next year we’re hoping to consider a whole range of possibilities.”

How the engineers feel after the past six months

At the press conference, Koji Sato, President of GAZOO Racing Company, shared the following thoughts on the evolution of the car.

The car as a whole is well-balanced and getting great lap times. At the Fuji race, we were competing with cars in the ST-5 category (the lowest class in which vehicles like Honda Fit and Mazda Roadster compete), but our lap times are now at the upper end of the ST-4 class (in which Toyota’s 86 competes).

We can now compete with cars in the ST-4 category within just six months because the hydrogen-engine car has been cultivated through motorsports at the racetrack.

Although it wasn’t discernible from lap times, we were previously doing a lot of work on the car at night in between qualifying and the final, but now we’re no longer seeing the need for major troubleshooting or large-scale changes, so race operations have stabilized substantially over the past half year.

We’ve made solid progress with managing various aspects of the car within the team, and have finally reached the level where we can really compete in races.

Not only were there quantitative achievements like lap times and other progress, but also changes in “the way team members work” in the pit. This feeling is also shared by the engineers.

“With mass production, you always proceed cautiously and tend to set time frames in alignment with various challenges. However, with motorsports, the deadlines come every 45 days, so you have to change the way you work. While we need to work hard to make visible improvements in a short time frame, we now have a sense of unity as a team, as we share ideas and take forward action together as one,” says Sakamoto.

“We’ve got this car in good shape within a short period of time. It is unprecedented that we accomplished this level for a fully redesigned vehicle in just six months,” adds Takahashi, expressing his growing confidence in this agile development style.

Next year’s Super Taikyu Series starts on March 19 and 20 at Suzuka Circuit. The ever-evolving hydrogen-powered engine will continue to be a topic of interest in the next season.