This two-part article introduces Hirotoshi Hikota, a master of facility maintenance who repairs the vast systems that keep the car production genba moving.

Handwork still plays an important role in today’s car manufacturing, even as technology like AI and 3D printing offer more advanced methods. This series features the craftsmanship of Japanese monozukuri (making things) through interviews with Toyota’s car-making masters.

This article showcases Hirotoshi Hikota, a master of facility maintenance who sustains Toyota’s production infrastructure.

#11: Hirotoshi Hikota, a master of facility maintenance, keeps plants and offices supplied with energy

Manager, Facility Support Section, Plant & Environmental Engineering Div., Toyota Motor Corporation

The facilities that power car production

Hikota is part of the Plant & Environmental Engineering (PE) Division that oversees the planning, design, construction, maintenance, and management of Toyota’s plants, offices, and employee facilities.

Toyota has 11 plants in Aichi Prefecture, eight of which are in Toyota City where the company has its headquarters. There, countless machine tools are operated round the clock, along with facilities such as air conditioning and lighting equipment that make work environments more comfortable for production staff. These plants are also accompanied by nearby offices and company dormitories.

An essential element for plants, offices, and dormitories alike is the energy that keeps them running. The role of Hikota’s group is to obtain electricity and primary energy sources from the relevant providers and convert them into a steady supply of electricity at the required voltages, along with other forms of secondary energy such as steam, cooled/heated water, and compressed air.

The PE Division has five Power Supply & Maintenance Sections to power Toyota’s facilities, and Hikota’s team supports them with 100 members.

Like the plants they look after, each Power Supply & Maintenance Section works non-stop, managing the operations of power facilities in three eight-hour shifts. Hikota’s Facility Support Section handles the vital task of servicing and maintaining these facilities. His team constantly monitors the state of equipment to prevent problems and respond swiftly when issues arise.

Hikota

We are the power behind the scenes. Our job is to provide a stable energy supply to the plant production floor. Failure to do that might delay production or compromise workplace safety. In more serious cases, it might cause a plant-wide shutdown or a serious accident, causing a great deal of inconvenience for customers whose cars don’t arrive on time.

That said, the facilities are prone to wearing out and contain parts with limited lifespans. Fixing broken machinery is both time-consuming and expensive. So, what is the best solution? As a facility maintenance engineer, Hikota has been tackling this problem since joining Toyota.

A boy who loved working with his hands

Hikota joined Toyota in 1985 after completing a mechanical engineering course in high school. Since then, his career at the PE Division has focused exclusively on facility maintenance.

Hikota

As a child, I always loved working with my hands. At home, my father made chairs, and for one summer project, I spent a month building a director’s chair out of the materials we had.

Hikota’s interest in Toyota was spurred by visiting one of the company’s plants as a boy.

Hikota

More than the car production line, I was drawn to the equipment that helps workers operate in a more comfortable position. Toyota was also my top choice because I wanted to be involved in making cars. I like making things. Some colleagues and I used caterpillar tracks to build a stair-climbing wheelchair, for which we received an award at the company’s Idea Olympics.At Toyota, Hikota’s first assignment was maintaining electrical equipment and machinery for company housing and dormitories.

Hikota

Despite my mechanical background, I worked in the electrical department. But the same goes for any company—there’s no telling which division you’ll be placed in. From that point on, I was determined to acquire professional skills I could use to earn a living, whether at Toyota or elsewhere. With that mindset, we took on some of the electrical work, plumbing, and various repairs ourselves, instead of relying solely on outside contractors.

Then in 1989, in his fourth year at the company, he was transferred to his current workplace at the Facility Support Section and tasked with running equipment diagnostics on power supply facilities throughout the company.

Power facility failures cause major problems for car production. Even brief stoppages on the production line result in enormous financial losses and delay customer delivery time. The machinery must be kept running with minimal stoppages, and any downtimes must be kept as short as possible.

From corrective to preventative, predictive maintenance

Hikota moved to the Facility Support Section at a time of major advances in the field of facilities maintenance.

Facilities maintenance has continued to evolve with the times. Initially, the standard approach was known as breakdown maintenance, which involved repairing equipment when problems occurred. The key here was to minimize the downtime required for repair.

However, dealing with breakdowns after the fact inevitably entails heavy losses. In response, the next approach brought a preventive mindset, known as time-based maintenance, which involved stopping equipment at predetermined times to ensure regular servicing and replacement of parts.

Despite this, shutting down facilities still ultimately lead to losses. Hikota transferred to the Facility Support Section just as another new approach emerged. In condition-based maintenance, sensors constantly monitor the state of facilities, and wherever possible, equipment is serviced without stopping operations. Repairs are quick and efficient, with shutdowns serving only as a last resort.

Such an approach relies on 1) daily inspections and simple diagnostics, 2) identifying problematic trends, 3) precise diagnosis as necessary, and 4) prompt overhauls and periodic maintenance.

Hikota

When a breakdown occurs, we thoroughly investigate the root cause to prevent the same thing from happening again. To do this, you need to understand the fundamental principles of that machinery or equipment, its workings, and operations, but in those days you could only get that knowledge through a look-and-learn approach.

Seeing how Hikota applied himself to learning, senior colleagues began to offer tips and advice.

Hikota

Condition-based maintenance is about using data rather than guesswork to determine how to maintain facilities. However, adopting this new approach was not that easy in the beginning. If we spent time analyzing data, those on the frontlines would say that “diagnosing doesn't fix equipment” or “the reports are too difficult.” Showing the data would not still convince them that repairs were really necessary... that’s how it was.

Hikota overcame each of these obstacles with persistent effort, including experiments to replicate the issues and diligent study to improve his knowledge and skills.

Hikota

Every time I failed to get people on board, I thought, “Oh, come on!” which drove me to work harder.

Bringing servicing in-house

In 1997, Hikota took on a new challenge to service and repair large-scale facilities by themselves, not by outside equipment suppliers.

Hikota

In the past, if we diagnosed an issue in our large-scale power facilities, we would ask the equipment manufacturers to conduct repairs. Doing that, though, meant that repairs inevitably take longer to complete. I set out to get various technical and national qualifications so that we could diagnose and fix even the larger power supply facilities ourselves.

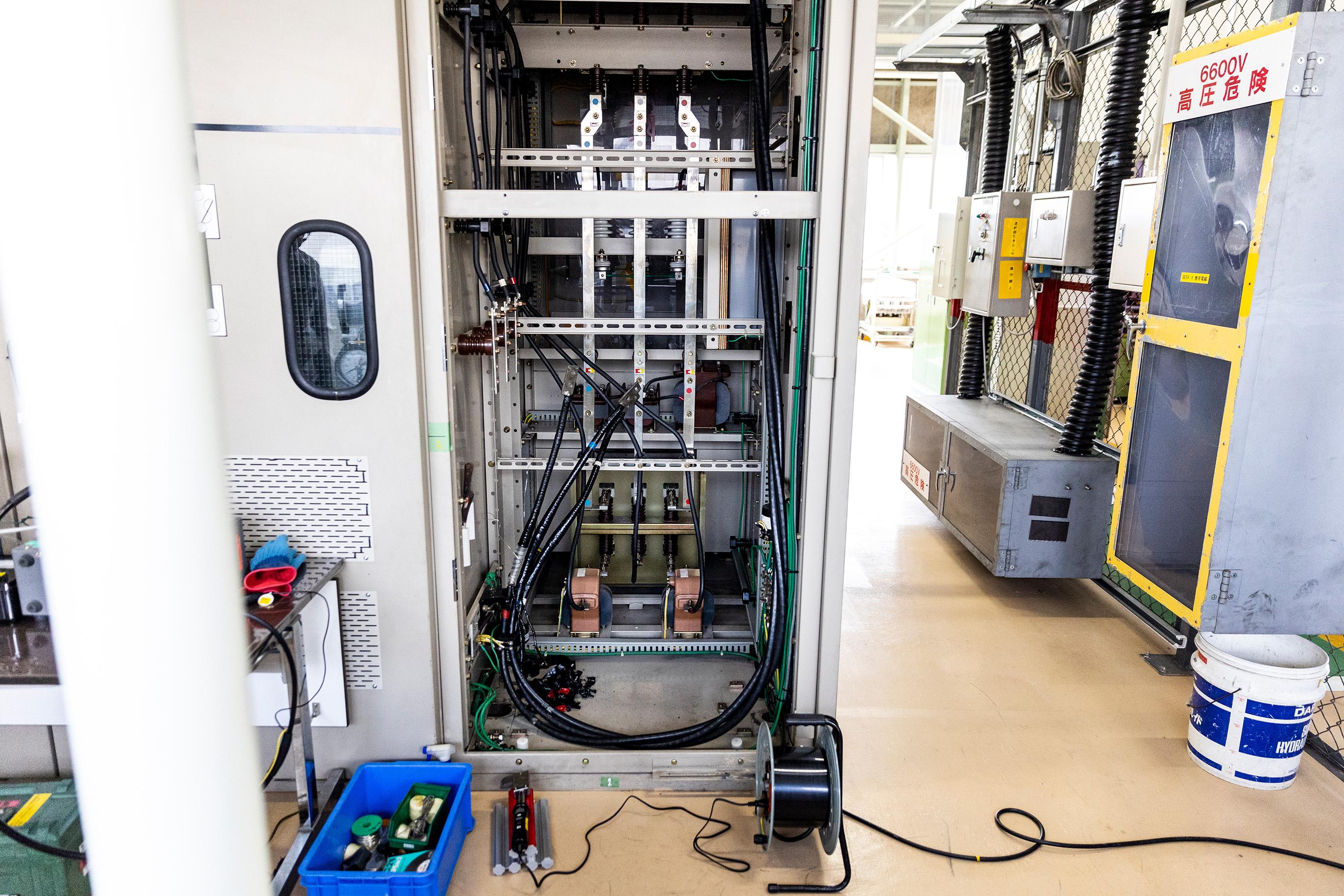

When Toyota Times visited, Hikota and his colleague Hiroki Ito, who also has a variety of technical and national qualifications, demonstrated how they diagnose and repair high-voltage cables.

Hikota

Chubu Electric Power Company supplies Toyota’s plants with electricity via transmission lines at a special high voltage of 77,000 or 154,000 volts. Transformers in our buildings drop that down to the optimum voltage for powering machine tools. Unfortunately, high-voltage cables are susceptible to water damage. For instance, even the slightest moisture ingress in the insulation layer can lead to water treeing, a phenomenon that may cause the insulation to fail, leading to dangerous short circuits. Since many processing machinery in plants runs on electricity, such accidents severely impact production.

When servicing high-voltage cables, team members identify issues using a device that detects electrical leakages. If water treeing is discovered, they promptly locate and remove the affected section using an electrician’s knife or other tools, then repair the cable with solder before wrapping it in electrical tape to prevent the problem from recurring.

Hikota personally demonstrated these skills in action, cutting a water treeing section with a customized single-edged electrician’s knife. He then repaired the line with a soldering iron before carefully winding two different electrical tapes, ensuring that half of their widths overlapped.

Hikota

High-voltage cables carry electricity at such high voltages that anyone coming into contact with them would be instantly killed. On top of that, the inside of a distribution box is cramped, so we sometimes have to work lying down. Even this taping process requires unique expertise.

Following the repairs, high-voltage electricity is run through the cable for a period of time to ensure that it has the necessary insulation. Only then is the job complete.

Members of Hikota’s team also demonstrated insulation measurements to diagnose insulation performance on both normal and damaged high-voltage cables. The team is set up to handle such diagnoses and many other tasks entirely on their own.

Hikota

It’s been 15 years since we began bringing this maintenance work in-house as part of the kaizen efforts of our team members, not because someone told us to do it. These days we do pretty much all of the power facilities servicing in-house. Doing the work ourselves has let us revise the company’s facility installation standards to reduce the likelihood of accidents.

Hikota is now also involved in disaster response. This includes restoring affected plant equipment and conducting rescue activities outside the company, as well as training the younger colleagues who will take on these tasks going forward.

The second part highlights these disaster recovery efforts, external activities as part of the section’s disaster rescue team, and developing personnel for the future.

(Text: Yasuhito Shibuya, Photo: Yuqi Zhang)