Morita's assignment was to investigate its future. In Nihonbashi, he visited Woven Planet Holdings, the company that's leading the Woven City project.

Toyota Times reporter Morita visited Woven Planet Holdings in Nihonbashi, Tokyo, to learn more about the development of Woven City, which is being built on the Higashi-Fuji Plant’s former site.

Woven Planet is a brand-new company that began operating in January 2021. Its forerunner, TRI-AD (Toyota Research Institute - Advanced Development), had been set up in March 2018 to develop and implement automated driving technology. It also served as a link between Japan and TRI, a development facility based in America’s Silicon Valley.

Then in January 2020, Toyota announced its plans for Woven City. TRI-AD was tasked with leading the project, instantly expanding its responsibilities.

A new structure was adopted in response to these changes. The holding company Woven Planet Holdings now oversees three operating companies – Woven Core, responsible for the development, implementation, and market introduction of automated driving technologies; Woven Alpha, tasked with exploring new business areas such as Woven City and Arene, an open platform for programming cars; and Woven Capital, an investment fund.

At the announcement of this new arrangement, President Toyoda shared his vision for the Woven Planet Group: “The one thing that will purposefully be missing from these 3 new companies is the ‘Toyota’ branding. Regardless, these companies will clear the path for the future of Toyota, as they carry on the legacy of ‘for the happiness of others’ that Toyota has so carefully woven into its own DNA.”

The task before Morita was to find out precisely how the development of Woven City was progressing. With the plans announced a year ago in January, construction had finally begun in February 2021. Just how far had the city’s development come? And how exactly do you go about developing a city of the future that is unlike anything seen before?

Morita reports from the Woven Planet offices

After passing through the entrance, Morita found himself in a space where the walls are covered with floor-to-ceiling screens, projecting images of Woven City. There he was greeted by Woven Planet Holdings CEO James Kuffner and Senior Vice President Daisuke Toyoda.

Kuffner:

We are really looking forward to having you experience some of the things we are working on, and to give you a sneak-peak of the feature.

Morita:

You mean we’re going to experience what the future holds?

Toyoda:

Past, present and future – I think you will see it all.

Near the entrance to the offices, the words ‘Mobility for All’ adorn the wall. The letters are designed to be readable not only with the eyes, but also by touch, as braille. This embodies Toyota’s vision of becoming a mobility company that ‘brings the joy and freedom of movement to all’.

The design of the meeting room area was inspired by the streets of Nihonbashi, where the office is located. Individual meeting rooms are named after countries – Finland, Denmark – conveying their purpose in considering the future of the planet as a whole.

Passages are marked with road signs, making the office feel like a simulated city. Perhaps the streets of the future, filled with electric scooters and self-driving robots, will be seen here first.

Kuffner:

It’s a Silicon Valley-style casual workplace, but also designed especially to support the Woven City team.

Morita:

There’s a road.

Kuffner:

This direction shows smiles.

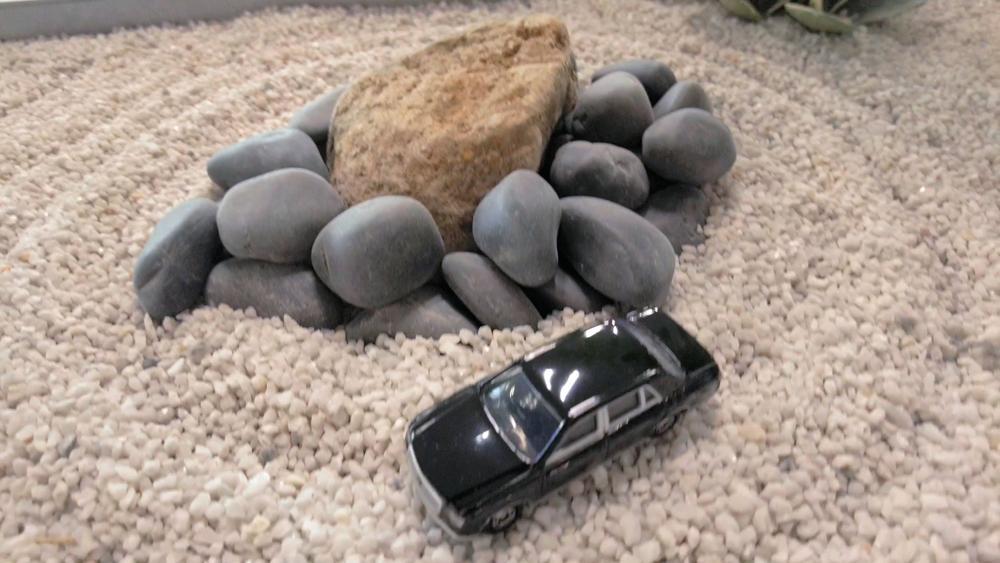

In one corner of the office, Morita discovered traces of the Higashi-Fuji Plant he had recently visited. Assistant of Relation Hub Chika Harata, who toured the plant prior to closure, had suggested and carried out the relocation of its zen garden to Nihonbashi.

Eager to connect Higashi-Fuji’s history and culture to Woven City in a tangible way, Woven Planet’s staff transported and assembled the stones by hand. Closer inspection revealed a miniature Century and JPN Taxis on display. Those high-quality cars that sustain Japan were built by us—the pride of the Higashi-Fuji Plant appears to live on among the Woven Planet Group employees in Nihonbashi.

Finally, Morita arrived at the floor of Woven City Management, which is engaged in the city’s development. Before him lay a detailed model of the entire Woven City, the area currently under construction accounting for only a fraction of the whole.

The development methods used here differ greatly from conventional urban development. As Woven Alpha Director of Service R&D Kouta Oishi explains, Woven City adopts a ‘software first’ approach, which means that the team begins by building digital models that help them figure out how to improve the real city.

Developing an entirely new city, unlike anything that has come before, requires extensive trial-and-error. In such cases, constructing physical roads and buildings from the outset would constrain flexibility.

Instead, the approach for Woven City looks to maximize development efficiency and speed through the potential of digital technology, which makes it possible to rapidly repeat the trial-and-error cycle before building a real city based on the results.

Woven City’s 3 development themes

The development of Woven City is divided into three main themes – Service Development, Product Development, and UX Development. During his visit, Morita received an introduction to all three.

First up was Service Development. Morita was shown around the development of a logistics center, guided by Akira Yoshioka from the TPS Group at Toyota Motor Corp., and Morihiro Masada, Product Owner of Logistics at Woven Alpha.

Masada explained how goods would flow around Woven City. The city’s logistics center will receive a wide range of deliveries, including from couriers, dry cleaners, retailers, newspapers carriers, and mail. These will be delivered to each home by an automated delivery robot.

Once loaded with goods at the logistics center, a delivery robot travels via underground passages to the residential buildings, where an elevator takes it up to the recipient’s room. There, it deposits the items in a ‘smart post’ mailbox at the home’s entrance, before returning to the center. Naturally, the entire process is automated.

It also works in reverse – the delivery robot will automatically collect any outgoing packages, dry-cleaning or rubbish placed in the smart post. Woven City basically does away with the idea of goods being shuttled back and forth above ground.

Morita:

Compared to how we live now, it saves a lot of work, doesn’t it?

Masada:

What we are aiming to do is eliminate the need to travel unnecessarily for routine tasks. In doing so, we want to free up more time for people to engage in activities that add greater value. That is the idea behind this approach.

In the center of the room stood a vast model, a 1:20-scale rendering of the logistics center that is to be built underneath Woven City. Masada used the model to explain the flow of a home delivery. When a delivery truck arrives at the center, workers transfer the goods onto delivery robots. Once loaded, a delivery robot automatically travels via underground passages to deliver the goods to each home.

Given that delivery is fully automated, it may seem strange that the loading and unloading of goods is done by workers. As Masada explains, however, this was a deliberate choice to bring people and robots together. In Phase 1, the volume of goods being delivered will still be small. According to Masada, at this stage full automation would be excessive and “could lead to facilities becoming entrenched in their ways.”

This is precisely the idea behind TPS (Toyota Production System), Yoshioka adds. TPS is a highly adaptable system. For example, trials might reveal that some residents prefer to receive their goods directly, rather than through smart post. Some may even choose to pick up packages in person instead of having them delivered.

Testing such options is the purpose of Phase 1. Systems and equipment that are put in place at this stage may take root and hinder future revisions. Instead, the development team seeks to build a foundation that will allow for rapid kaizen, minimizing equipment to enable constant evolution.

Morita:

If you automate it fully from the start, you won't be able to tweak it anymore, right?

Yoshioka:

We wouldn’t be able to.

Morita:

So the idea (of Woven City) being ever-evolving is reflected in these areas as well.

Yoshioka:

That's right.

The TPS Group’s Yoshioka is a specialist in implementing the kaizen cycle at Toyota’s plants. For this project, however, the genba does not yet exist. In order to begin the kaizen process, the team must first build a genba, even if only temporary.

Toyoda:

With cars, you can build a prototype, but a city is different. No matter how much we call this a ‘prototype city’, we can’t simply build it like we would a prototype car. You don’t have the ability to build and then rebuild again.

We need to iron out the issues beforehand, and because certain things are unclear on paper, we make physical models. Even with this, there are aspects that we can’t fully examine, and so we use digital tools for them. Issues that come up in the digital environment are fed back in here, then we repeat the cycle again. That’s our process.

Morita:

I imagined that everyone here was just working on computers, tweaking graphics on the screen. To be honest, I was quite surprised when you started off by showing me this handmade diorama.

A logistics center inside the office?!

“Here we are.” The doors opened into a sight that seemed far removed from a cutting-edge office. On the other side lay a reproduction of the logistics center that the team plans to set up beneath Woven City. The entrance featured a gate emblazoned with the slogan ‘Safe work, reliable work, proficient work’; beyond flashed the red, yellow, and green signal lamps commonly found in factories.

Turning around, Morita found himself facing a realistic reproduction of a truck’s cargo space. As a nice added touch, the green license plate shows ‘223’, which can be read as ‘Fuji-san’ in Japanese and is also the date marking the start of construction for Woven City.

The cargo space itself was loaded with cardboard boxes. Unloading these boxes is the first step in the logistics center’s operations.

The rest of the process was demonstrated by Shogo Momoshima from Sales Logistic IT KAIZEN Div. Scanning a box’s delivery slip with a smartphone brings up detailed information about the package on an adjoining tablet. Tracking a package using IoT provides access to important information, such as delays and progress, in real-time.

Once the package’s details have been obtained, a smartphone app displays instructions on which box and delivery robot it should be loaded into. The system calculates the most efficient delivery route currently available.

When all of the items have been loaded on, the operator can give the signal for departure via the app. As the delivery robot sets off, another comes into the standby position.

Although the system already looks rather complete, Momoshima insists that this is merely the base state prior to kaizen. In other words, having reproduced the genba in such detail, the team is finally ready to begin the kaizen process.

As Yoshioka explains, establishing standard operations in this way “gives a clearer picture of our base levels.” These base levels, which refer to the standard amount of man-hours, materials and other inputs required, underpin the TPS approach. The team will use these levels to create the center’s layout and operations. President Toyoda has himself stated that “our first goal for Woven City is to define our base levels.”

Every aspect of the logistics center genba reproduced here was conceived and hand-built by Toyota’s kaizen persons. Despite their efforts, however, when faced with a challenge as vast as a city’s logistics, there are limits to what can be achieved in a genba of this size.

To overcome these limits, the team used the base levels defined here to create a digital rendering of the logistics center, enabling them to test how the system handles fluctuations in the flow of goods.

Masada:

What we are trying to do here is to combine Toyota’s DNA, TPS, with a digital twin.

How a digital twin speeds up development

What did Masada mean by ‘digital twin’? That explanation was provided by Nobuhisa Otsuki, Product Owner of the Digital-Twin Simulator at Woven Alpha. As the word ‘twin’ implies, this approach involves producing an identical digital copy of the real world that can be used for simulations. Here, the team has constructed a digital version of the logistics center, which is used to simulate various scenarios.

Otsuki:

We can input many different situations – for example, if there are far more seasonal gifts arriving than usual, or if one of the service staff is absent with the flu – and simulate how they impact the service, and our customers.

Morita:

And if you do that, you get actual problems arising in here?

Otsuki:

Yes. For instance, if an increase in the volume of goods causes robot congestion at a certain intersection, or if something that should arrive in one hour actually takes one and a half or two, we can see all of these outcomes via visualizations.

This allows us to identify the causes. It might be that there weren’t enough robots available, or they didn’t have enough time to recharge. We give feedback on these issues to the project team, which leads to kaizen such as faster battery replacement or increasing the number of robots on standby.

Facility layouts that are difficult to revise in the real world can be rapidly changed in the digital realm, making it possible to experiment with countless configurations. The unique capabilities of digital tools help developers to identify problems more clearly, opening up greater scope for improvement.

At this point, Morita was struck by a sudden thought – why not just handle everything digitally from the outset? But as Otsuki explains, it’s not quite so simple. There are just too many unknowns. For example, aspects such as human motion, fatigue, or efficiency of movement are impossible to recreate accurately without testing in the real world.

Then there may be tasks that, while simple in digital simulations, turn out to be rather difficult in reality. This is why the team approaches the TPS kaizen cycle with a combination of real genba and digital twin.

Morita:

At some stage you will take these to Higashi-Fuji and actually start building, right? How will you know when the time is right?

Otsuki:

I think we’ll probably keep up this constant kaizen cycle even after the place is open. We will continue to simulate the best available options, then the next day feed them back into the kaizen cycle. I think that process will continue for a long time.

Digital tools offer an early taste of the future

“We’d like to give you a sense of what the streets will actually look like,” Toyoda informed Morita, standing before a door. Inside, explained Wataru Kaku, Lead of Digital Product at Woven Alpha, was a room where one could enter a VR environment without wearing VR goggles. The interior was still off limits to cameras, so Morita went in alone, but his comments offer a hint of what lay in store.

Morita:

Ah, it’s true – even without goggles, the surroundings react to my movements. Oh, the sun is really bright in this spot. It really feels like being there, especially without wearing goggles.

Ah, this side goes all the way back. There are people too. A robot just went by!

Even more astonishing was the fact that this setup can display real people in the VR environment in real-time. Here too, the details are still confidential, but one imagines a 3D person projected in the space, like something out of a science fiction movie.

Kaku:

Unlike ordinary video conferencing, this lets you show what someone is looking at, or what they are pointing at. I think this would be extremely helpful in, say, a piano or dance lesson with complex movements, or perhaps a meeting in which many people are looking at and discussing a single object.

An explanation of the UX development was provided by Satoshi Okamoto, Director of UX Communication Strategy, Woven City, and Matthew Doell, Universal Exports Head of UX Simulation. This is where Woven City’s digital twin is being developed. Donning a pair of VR goggles, Morita found Woven City spreading before his eyes, cherry blossoms in full bloom.

“It’s Mt. Fuji, just as I remember it,” exclaimed Morita, completely immersed in the virtual Woven City. “Majestic Mt. Fuji!” Creating this virtual world allows the developers to evaluate how people actually feel in the environment. Rather than relying on individual impressions, it also allows people from around the world to access the same space and provide feedback.

Okamoto:

What we are trying to do here is make something that is human-centered. It’s about the lifestyle. That’s why it’s extremely important for us to use these digital settings to see and instinctively assess how people live in those environments.

People and robots living side-by-side

In the product development area, the team had recreated an entire home. Stepping inside, Morita was greeted by a robot whizzing towards him. This in-home delivery robot automatically collects any boxes delivered to the smart post beside the entrance.

As the robot drew near, the post’s door opened. The delivered items were loaded onto the robot, which then automatically carried them to a shelf for storage. “I think it will be very convenient for elderly people who have trouble carrying heavy objects,” anticipates Kunihiro Iwamoto, Lead of Hardware.

Lead of Robotics, Yutaka Takaoka, demonstrated a robot that moves around the ceiling. He regards this as the best way to navigate smoothly around a cluttered house. The robot is equipped with an arm that allows it to recognize and hold objects, an ability it demonstrated by lifting a cup. Takaoka hopes that this can be used to wash dishes in the kitchen, clean bathrooms and toilets, or tidy around the house.

Morita:

But isn't it a little scary as well, when it moves so fast?

Takaoka:

These are exactly the sorts of things we want to explore. How fast should it be, for example? As we research and develop these robots, there are things that we just don’t know. That’s why we have a real house where customers can actually come and tell us what speed works best for a robot like this, or what applications they find useful. That’s one of the big reasons for setting up a real house to use as a laboratory.

The digital twin was being put to use here as well. Trying to test all conceivable scenarios in the real world would take an enormous amount of time. However, by setting up one hundred simulations to run in parallel, for example, testing that normally takes more than a year could be completed in a single night. In this way, software development also employs a combination of real and digital methods.

As he watched the robots taking care of every detail, Morita wondered whether some people may not want everything to be done for them. “We don’t want to force anything onto customers just because we think it’s convenient,” responded Takaoka.

Whether something is convenient depends on the values of each individual, so it is important to provide many alternatives. At this stage, the team is exploring various approaches in order to demonstrate as many options as possible, which is a major reason behind the construction of Woven City.

Everything is ‘interconnected’ in Nihonbashi

When Morita visited Higashi-Fuji for the Woven City groundbreaking ceremony, the as-yet empty site left him unconvinced that much was really happening. Upon spending a day reporting in Nihonbashi, Morita was astounded to find a recreated logistics center and home interior, along with detailed simulations of the city and lifestyles of the future.

At the same time, the offices provided constant reminders of how the various elements interconnect, from the ‘software first’ approach and the Toyota Production System, to objects that carry on the legacy of Toyota Motor East Japan employees who worked at the Higashi-Fuji Plant.

And, whether he was aware of it or not, Morita’s own hopes for the future also seemed to be seamlessly connected.

Morita:

Personally, I can still vividly remember the sense of excitement about the future that I felt as a news presenter when reporting on President Toyoda’s CES announcement of the Woven City project. I’m thrilled to be able to cover it from the frontlines like this, and I look forward to following the progress of Woven City.

For now, that’s all from here in Nihonbashi!